Andrew Glester reviews For Small Creatures Such As We: Rituals and Reflections for Finding Wonder by Sasha Sagan and interviews the author

Most readers of Physics World will be familiar with the works of astronomer Carl Sagan, and the writer and producer Ann Druyan. The husband and wife duo worked together to write, produce and present the seminal 1980s TV series Cosmos, which was, and still is, one of the most watched and beloved science TV productions ever made. Despite its broad-ranging coverage of many scientific subjects, Cosmos was successful thanks to the perspective it offered to viewers. It deftly showed us – the Pale Blue Dot – our place in the universe.

Indeed, Sagan and Druyan’s productions were celebrated for their art as much as they were lauded for science communication. Following in their footsteps, daughter Sasha Sagan has now penned her first book, For Small Creatures Such As We: Rituals and Reflections for Finding Wonder, in which she attempts to unravel the meaning of life, via the many rituals that we attach to big moments of change in our lives. Where her parents looked to the stars for inspiration, Sasha Sagan’s gaze is more squarely on the human condition. Can those with a secular world-view learn from the rituals mainly practised by those of the different faiths around the world? Sagan, who was herself raised in a secular home, finds that science is at the root of many ritual celebrations in cultures across the globe.

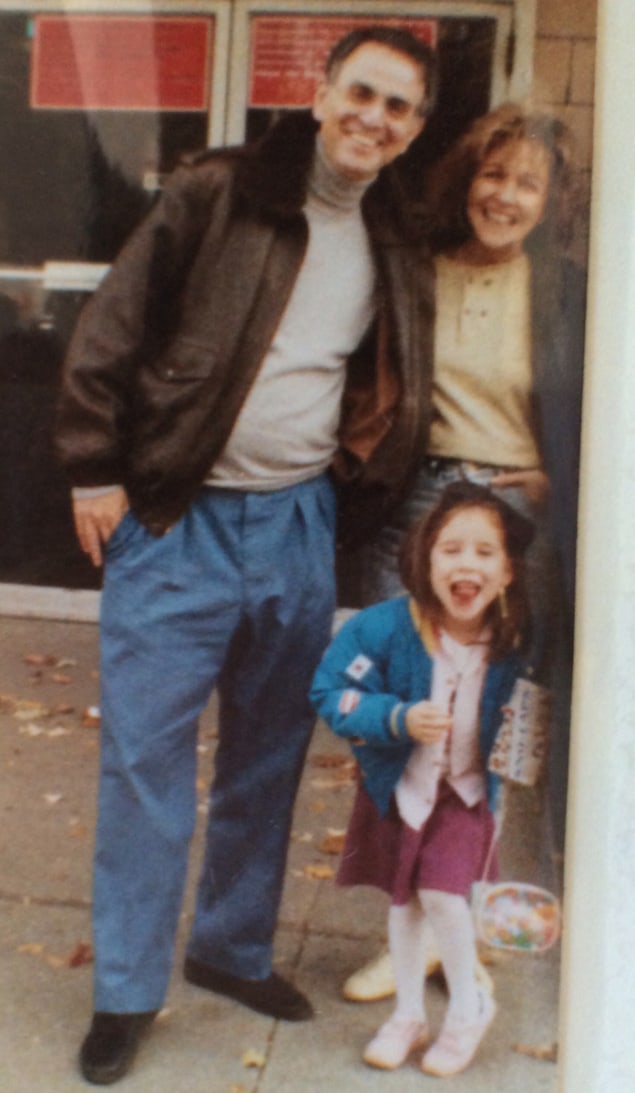

For Small Creatures Such As We explores these rituals and practices we humans punctuate our lives with. From major life events such as births, marriages and deaths, to the more mundane such as eating, sex and atonement (those two are not necessarily linked), the book considers how someone with a secular worldview might find the same solace and celebration without the trappings of religion. Sasha Sagan’s love for her parents, and the inspiration she takes from them, is evident throughout, with the title itself drawn from their writing. Families play a large part in most of life’s events, in one way or another, and Sagan’s writing turns the lens on her own experience as much as it draws from cultures around the world.

Topics include death, fasting, feasting, the seasons, plus weekly and monthly rituals. Sagan’s tone is personal and amusing, as she shares stories that are intimate, open and honest. While she considers many practices from around the world, it is the individual who receives most focus: the personal benefits and pitfalls. It’s clear that the death of her father and the birth of her daughter have played a large part in inspiring Sagan to wonder how people who have no religion might learn from those who do. Learning is not always about how to do something but, on occasion, how not to. There is humour in some of the culturally strange practices, but Sagan writes with neither malice nor judgement. No worldview is presented as worse or better than another – except where that worldview leads to actual and clear damage to human beings.

Considering the burial rituals of people from Vietnam to Madagascar, from the Amazon to the Great Lakes, Sagan turns her thoughts to the funeral of her father, who died in 1998 aged 62. As a 14-year-old in the middle of grief, she tried to shut down her feelings to an extent, to keep the emotions at bay. Writing about the birth of her daughter, Sagan looks back through the lens that life and research into distant communities has given her. She wishes she had let herself experience those feelings in full at the time. It is an emotional passage in a book that, as a whole, deftly navigates weighty topics with humour and a real sense of understanding.

Standing on the shoulders of giants can be a help as much as a hindrance. Without skill, you run the risk of filling your work with clichés. Sagan avoids this adeptly and her writing is imbued with a passion equal to that of her parents. The book sits somewhere between a memoir and an exploration of social history. There is anthropology, science and the human experience. I was left with the feeling that I will turn to it again, for inspiration or reference, and For Small Creatures Such as We now sits on my shelf as a handbook.

In an interview for my podcast The Cosmic Shed, I asked Sagan about her book, and her parents’ legacy.

What was your inspiration for the book?

My parents raised me with awe and wonder for the universe as revealed by science. As a secular home, we had some traditions carried on from our ancestors. The philosophy was wonderful: it fulfilled some deep philosophical and intellectual needs. But what it lacks is celebrations, holidays and rites of passage. I became very interested in that sort of thing. I lost my dad when I was 14, and the question of how you grieve and mourn without the infrastructure of religion became very central to my life. I began researching celebrations and rituals and all sorts of ways that human beings mark change and the passage of time.

I found an astonishing thing, which is that much of what we do is the same around the world. When you peel back the specifics of time and space, when you take away the set design and the script and the elements of theatre, the actual cause for celebration – the changing of the seasons, the equinoxes, solstices, and biological changes like coming of age – these are all scientific events. My book is an exploration of that, and I try to light-heartedly explore some big questions such as science, religion and death but with a little humour in there.

The book considers “rituals and reflections for finding wonder” – tell me a bit more about that

In the recent history of human beings, religion and science have veered apart – we have this sense that the two are opposed. My mother calls it Post-Copernican Stress Disorder. The rituals and rites of passage and these huge moments in our lives; the framework for marking them is often religious. I think that, if you go back far enough, science – in the sense of following the evidence to understand where we are, what we are doing, how things work, how the seasons change, when the crops come, what the animals are doing, what the stars are doing – and the feeling of being part of something grander than ourselves…I think those things are deeply connected and they can be and should be.

We malign facts as “cold and hard” and we have this idea that when we understand something deeply, it takes away the “magic” of it. I think that it is the opposite. I think that the more deeply we study something and understand it, that’s a way of honouring it and celebrating it. We can all have that excitement about the elements of existence we’re curious about and want to understand, if we get this idea that there is beauty and awe and wonder in the way things really are. It’s so powerful.

Change is constant and we live on a planet where nothing stays the same. There are cyclical changes like the seasons and there are permanent changes like birth and death. It is really hard to wrap our minds around them, to process them and come to terms with them. We don’t have to look at life through a religious lens to know that when it is cold and dark, we need to party! We need delicious food and to all come together to get through the time when the days are really short. I think that many of the celebrations that we have created, around the world, are just ways of processing change and whether you believe or not, you still have to process those changes.

One of the biggest changes is the loss of a parent. A lot of people, even those without a strong faith, might find themselves turning to that faith for solace. Can you tell me about that for you?

When I lost my dad he had been sick on and off for two years but I just didn’t think he was really in mortal peril until the last few days. Maybe because I was naive, being so young, or I was in denial, or because my mother is a very optimistic and positive person. I took a really long time to wrap my head around what had happened. I think if you are brought up with faith and then you leave it, there can be a tendency to think, “this is what I can go back to in a difficult time” but because I wasn’t really brought up with it I don’t think that way.

My family is Jewish: we celebrate Jewish holidays, if I take a DNA test it says “you are Jewish”, but not in a theological sense. In the funeral there were some things that we did for my father, for my grandparents, that fit into the religious framework because it’s a recipe for how to deal with things in a situation. But I think that is something different from belief. Everyone has to navigate those traditions for themselves and I think there’s some value in having an idea about what to do when you are really stressed in that moment of grief – where it’s almost happening in slow motion and you’re not really experiencing it in your true self.

The message that I got from my parents about loss and death was that this does not go on forever – that what we are experiencing right now is very hard and painful, but it does go away. In fact, in some way that is what makes this moment so special. There are also other things that are amazing, if you take a step back. I literally carry on my father, thanks to a secret code in my blood that connects me to him, and all these ancestors I didn’t know. When my daughter was born, he lives on in her too, which is so magical. If only genetics was presented as this magical thing, instead of just worksheets you get in seventh grade. My parents wrote a beautiful passage about the written word being a magic trick – a way that someone who has been dead for a thousand years can talk to you inside your head. These things can seem almost supernatural, but require no faith and they give me a lot of solace.

You’ve been a TV producer and are now an author. That certainly follows in your parents’ footsteps but there is one thing that seems to be missing. Did you not want to become a scientist?

I think there may be a word missing from the English language because science is my passion and my worldview. I think of it like this – not every Catholic is a priest. It’s not my job. It wasn’t my strongest subject in school; I was much more of a history and literature person. It is something I read about a lot and it is a source of great inspiration. But I wish there was a word that means my philosophy is evidence-based and science is the lens through which I see the world. If someone says “Do you believe in X, Y or Z?” I often say “My position is I withhold belief without evidence.” I wish someone would invent a word for that philosophy: “I’m not saying there is not a ghost in your attic. I’m just saying that until I have evidence, I will not say I believe in something.”

Is that not scepticism?

Well, scepticism does not have a very friendly connotation. I want this imaginary word to have a joyful enthusiasm about that which is supported by evidence.

OK. I’m going to call it Saganism.

Well, it’s catchy. I’ll give you that.

It sounds a bit like paganism, which is difficult.

Not to mention Satanism [laughs]. I don’t want to get mixed up with that.

- 2019 Murdoch Books 288pp £14.99