Freak waves can appear suddenly and without warning. They are difficult to predict, tower above the surrounding waters, and remain the main suspects when a large ship goes missing. And curiously, before 1995 – when one such wave was recorded to crash into the Draupner oil platform in the North Sea – most evidence of their existence was anecdotal.

But now, researchers from the Universities of Oxford and Edinburgh have finally uncovered the mystery behind these freak waves. They found that when two waves meet at large angles, the height of the resulting wave is not limited in the same way as it would be in other situations.

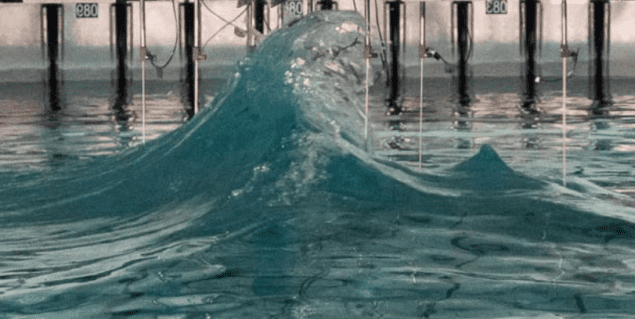

To illustrate this, the scientists simulated the formation of a freak wave in the lab. They were surprised when their creation showed an uncanny similarity to Katsushika Hokusai’s masterpiece “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” from the early 1800s.

Their work was published in the Journal of Fluid Mechanics

In an effort to make quantum mechanics reach high-school level classrooms, researchers from the University of Innsbruck, Austria, have created a game as a teaching tool. It conveys some basic concepts from this notoriously difficult field, but without requiring any knowledge of advanced mathematics.

In the game students are split into two teams called “particles” and “scientists”. The goal of the scientists is to perform “measurements” on the particles, who are told to obey specific rules. Then the former must try to come up with theories that explain their observations. The game aims not only to teach new concepts, but also to develop students’ critical thinking.

The game was tested in May 2018 with the three science classes of Colegio JOYFE in Madrid and was well-liked by the students participating.

At the start of 2019 the Doomsday Clock – which was created in 1947 to measure the world’s susceptibility to an apocalypse – remains at 2 minutes to midnight. While the clock hasn’t moved forward over the last year, it is a reminder that things aren’t really improving either. Nuclear modernization, climate change and growing misinformation remain big threats to humankind and our planet.

The clock, which was initially set 7 minutes to midnight, was created by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. The last time it was as close to midnight as it is now was in 1953, when the Cold War arms race escalated with the US and Russia’s hydrogen bomb tests.