Evidence of a minuscule force that could exist between two particle spins over long distances could be lurking in magnetized iron under the Earth’s surface. That is the conclusion of a new study by physicists in the US, who have used our planet’s vast stores of polarized spin to place exacting limits on the existence of interactions mediated by unusual entities such as “unparticles”.

The intrinsic angular momentum, or “spin”, of a particle gives that particle a magnetic moment, and the interaction between spins generates magnetism. A ferromagnet, such as iron, becomes magnetized when the spins of some of the electrons in its constituent atoms line up, while quantum mechanics tells us that the magnetic force between spins results from the electrons exchanging “virtual” photons.

Some theoretical physicists have suggested that other, as-yet-undiscovered particles might be exchanged virtually and so give rise to new types of spin–spin interaction. In 2007, for example, Howard Georgi of Harvard University proposed the existence of unparticles, which would have the unusual property that their masses would scale with energy or momentum.

Searching in the lab

To date, physicists have searched for such interactions using laboratory-based sources of particles with polarized spin – the idea being to monitor any change in the energy associated with the spins as their polarization is shifted relative to that of a set of particle spins in a detector. So far, such tests have come up empty-handed, but researchers continue to make their devices ever-more sensitive in order to progressively reduce the maximum strength that such a force could have.

In the latest work, Larry Hunter and colleagues at Amherst College in Massachusetts, together with Jung-Fu Lin of the University of Texas, Austin, use the Earth, rather than a laboratory device, as the source of polarized spins. The idea is to use the spins from unpaired electrons in the iron present in the Earth’s crust and mantle that are lined up by the planet’s magnetic field. A disadvantage of this approach is that these spins are, on average, thousands of kilometres from any detector, thus rendering the interaction between individual spins far weaker than would be the case with a lab-based source. But Hunter and colleagues worked out that this drawback should be more than compensated for by the sheer quantity of aligned spins in the Earth (they calculate that there should be some 1042 spins) and the fact that some of the interactions hypothesized by theorists drop off relatively slowly – in inverse proportion to the distance or the distance squared, rather than the distance cubed as is the case with magnetic-dipole fields.

Experiments in a spin

To put their approach into practice, the researchers were able to use results from three existing experiments. Two of these – one at the University of Washington, Seattle, and another, operated by Hunter’s group, at Amherst – were designed to measure a tiny hypothetical angular dependence of the laws of physics known as Lorentz-symmetry violation. The fact that the detectors in these experiments were placed on a rotating turntable makes them also well suited to measuring any long-range interaction with spins in the Earth’s interior. The polarization of the source – the Earth – is not reversible, but the polarization of the detector is.

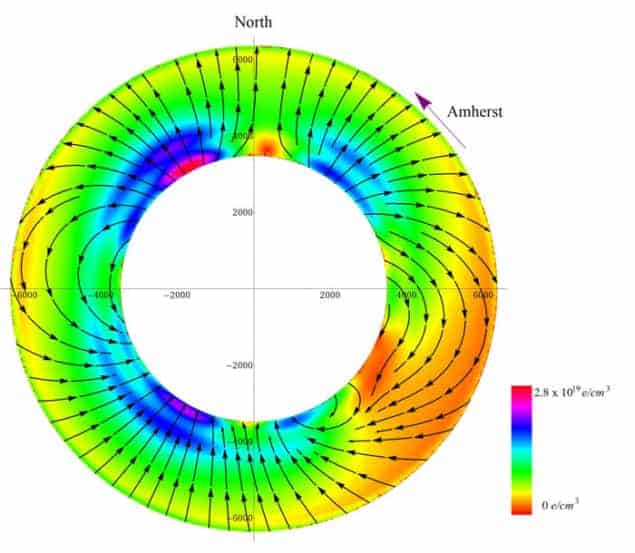

The researchers also made a map of the Earth’s polarized electron spins, drawing on data that showed the variation of temperature, magnetic-field direction and magnitude, and unpaired-electron density throughout the Earth. They then calculated the potentials associated with each of the anomalous spin interactions, integrating across the whole of the Earth and working out the effect of these potentials on the detectors in Seattle and Amherst. In this way they were able to reduce the upper limit of the forces associated with the exchange of unparticles, as well as with particles known as axial bosons, by a factor of a million. “In our obscure business of precision measurements it might take a decade to improve the sensitivity of an experiment by an order of magnitude,” says Hunter, “so using just laboratory sources it might have taken 60 years to get to the limits we did.”

Better off in Thailand

Hunter says that his group could further increase the sensitivity of its experiment by a couple of orders of magnitude once it has corrected a number of “systematic effects”, and he believes that rival groups might arrive at similar sensitivities. He also points out that further improvements could be made by placing the experiments in a more-suitable location, estimating that the stronger and better-aligned magnetic field that exists in southern Thailand would lead to a doubling in sensitivity compared with that attainable in Amherst.

Hunter adds that the discovery of a new long-range spin–spin force might also lead to improved mapping of iron concentrations in the lower mantle, given the limited data available from more conventional geophysical and geochemical observations.

“Clever and creative”

Derek Jackson Kimball of California State University, East Bay, describes the latest work as “a remarkably clever and creative new approach to the ongoing search for new fundamental forces of nature”, adding that it “will surely be useful for guiding the development of new theories and experiments that seek to explore physics beyond the Standard Model”.

Meanwhile, Eric Adelberger of the University of Washington says that when he first heard about the Amherst work, he was “amazed at the large claimed size of the Earth’s spin source and was sceptical” about the researchers’ claims. But he says he changed his opinion once he read the research in detail. “Their work is a real contribution,” he adds. “The moral is not to trust one’s ‘gut reaction’ – in my case that the effect was not large enough to be interesting – but to undertake a real calculation.”

The research is published in Science.