The average snowpack in western states of the US has declined by 15–30%, Philip Mote of Oregon State University, US, and colleagues found, losing an amount of water comparable in volume to Lake Mead, the largest manmade reservoir in the region.

“It is a bigger decline than we had expected,” said Mote . “In many lower-elevation sites, what used to fall as snow is now rain. Upper elevations have not been affected nearly as much, but most states don’t have that much area at 7,000-plus feet.”

The snowpack decline is due to warming rather than a lack of precipitation, the researchers believe. Higher temperatures earlier in the spring mean water will not be stored as long in the mountains, potentially causing lower river and reservoir levels in the late summer and early autumn.

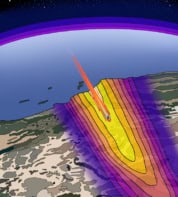

Mote and colleagues used data from 1,766 sites in the western US, focusing on measurements on 1 April, historically the high point for snowpack in most areas. They also looked at data from 1 Jan, 1 Feb, 1 March and 1 May, which gave the decline a range of 15–30%. Their physically based computer model of the hydrologic cycle incorporated daily weather observations and computed the snow accumulation, melting and runoff to estimate the total snowpack in the western US.

“We found declining trends in all months, states and climates,” said Mote, “but the impacts are the largest in the spring, in Pacific states, and in locations with mild winter climates.”

The Pacific states – California, Oregon and Washington – receive more precipitation because of the influence of the Pacific Ocean, and more of the snow falls at temperatures near freezing. The Cascade Mountains, which transect the region, are not as steep as the Rocky Mountains so they have more area that is affected by changes in temperature. “When you raise the snow zone level 300 feet, it covers a much broader swath than it would in the inland states,” said Mote.

Eastern Oregon and northern Nevada showed the most significant decrease in snowpack, though snowpack decreases of more than 70% also occurred in California, Montana, Washington, Idaho and Arizona.

Mote believes that the solution isn’t infrastructure as new reservoirs could not be built fast enough to offset the loss of snow storage and there’s not much capacity left for that kind of storage. Instead the answer is to manage what the region has in the best possible ways.

“The amount of water in the snowpack of the western United States is roughly equivalent to all of the stored water in the largest reservoirs of those states,” Mote said. “We’ve pretty much spent a century building up those water supplies, and at the same time the natural supply of snowpack is dwindling. On smaller reservoirs, the water supply can be replenished after one bad year. But a reservoir like Lake Mead takes four years of normal flows to fill; it still hasn’t recovered from the drought of the early 2000s.”

So far in 2017–2018, snowpack levels in most of the western US are lower than average, according to Mote, a function of continued warming temperatures and the presence of a La Niña event, which typically results in warmer and drier conditions in most southwestern states.