Pierre-Gilles de Gennes: a Life in Science

Laurence Plévert

2011 World Scientific £32.00/$48.00pb 372pp

This summer I took a break from lecturing at a graduate training school in Boulder, Colorado, to attend a talk by the soft-condensed-matter physicist David Weitz. His lecture was about colloids, and in the middle of it, he began to reminisce about the field’s early days. Weitz is now at Harvard University, but in the mid-1980s he was working in Exxon’s research and development centre in Annandale, New Jersey – a key international node in the development of soft-matter physics. The Annandale centre hosted some of the first conferences that catalysed the field’s formation, but as Weitz explained, the conference organizers had a problem: nobody knew what to call this new kind of research. After some debate, he recalled, they fell back on the only internationally comprehensible name they could think of: “De Gennes physics”.

That the name of Pierre-Gilles de Gennes should become attached to an entire area of physics indicates his stature as an extraordinary visionary, one who spent his life transforming existing fields, such as superconductivity, and creating brand new ones, such as soft matter. He won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1991 for his application of methods from condensed-matter physics to liquid crystals and polymers, but he also made his mark by exploring new ways of using theory and interacting with experiment, challenging entrenched institutions and becoming a passionate advocate of education. And of course, he topped it all off with a colourful personal life, in which he fathered two families of children and became a serious amateur artist. Small wonder, then, that an English translation of Laurence Plévert’s biography Pierre-Gilles de Gennes: a Life in Science has been eagerly awaited.

Plévert, a journalist, began interviewing De Gennes in 2005 – two years before the latter’s death. Author and subject worked from notebooks of jottings made by the latter over a 40-year period, and a long list of colleagues, family, collaborators and friends also contributed. The result is a thoroughly researched book. Even one of De Gennes’ closest friends, Phil Pincus of the University of California at Santa Barbara, found that Plévert unearthed episodes they had never spoken about. In Pincus’ case, it was De Gennes’ part in France’s North African nuclear-weapons tests that emerged from obscurity. For me, there was much in the book to fascinate and provide depth to this inspiring character, whom I had known since first meeting him during my PhD in the mid-1980s.

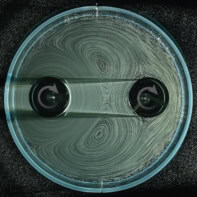

For example, in the first chapter Plévert gives the De Gennes family’s unusual history of French Protestantism an in-depth treatment, suggesting a thought-provoking connection to De Gennes’ later trajectory as someone whose thinking was strongly differentiated from traditional French theoretical physics. Similarly, anecdotes from his postdoctoral period with Charles Kittel in stylish and sunny 1960s Berkeley somehow resonate with his later ease at combining the serious with the flamboyant. I was also unaware of just how closely De Gennes was involved with early neutron-scattering experiments on vortex lattices in type II superconductors. Such close collaboration between theorists and experimentalists gave the French researchers an edge, and characterizes much of the methodology of soft-matter physics today.

After describing De Gennes’ childhood and early career, the book’s narrative tangibly picks up pace when it turns to his time as an assistant professor in Orsay, where his leadership potential first became apparent. De Gennes founded a superconductivity research group there in 1961, only to divert the entire group to the new field of liquid crystals after seven years. Later, at the Collége de France, he did the same with the wider field of soft matter. Plévert keeps this career-related thread ticking along in an accessible manner, weaving between general-audience explanations of techniques such as the renormalization group (one of the methods that De Gennes took from mathematical physics and planted in a new area) and diatribes against his subject’s bêtes noires. These were many and varied, and included conservative traditions in science, the pursuance of long-dead scientific questions, over-formal methods in science education and the editorial prevarications of Nature (after an invited article was rejected, he refused further invitations to write for the journal).

The other thread in the book’s tapestry is De Gennes’ personal relationships, both public and private, and the author treats these in a sensitive and candid way. De Gennes maintained two families, one with his wife Annie and one with his colleague Françoise Brochard-Wyart. The pain this arrangement sometimes caused to those close to him, and the ways in which their resilience permitted it to work, receives the most gracious treatment of the book.

Altogether, A Life in Science is a compelling read, but I came away from it with the impression that its propulsive energy had all come from its subject, rather than its author. Perhaps this is appropriate in a biography, or inevitable in one that attempts to capture greatness. Still, it ought to be possible to make more out of De Gennes’ life than this series of events, anecdotes and aphorisms, however carefully chosen and connected. The author has identified some deep-lying themes, but somehow, they never quite lead to a biography greater than the sum of its parts. Perhaps De Gennes needs a scientific biographer, someone who could be to him what Abraham Pais was to Bohr and Einstein.

The book also contains some annoying technical errors and typos, and this rather lets down an account of De Gennes, who was a scrupulous scientist. For example, the probability that a dropped needle intersects one of a series of parallel lines separated by its own length is 2/π not “2/x”. Such faults are redeemed somewhat by an appendix of technical details, but that, in turn, misses a trick by omitting any references. In addition, the anonymous translator and editor have failed to erase mannerisms that, even if they work in French, most certainly do not in English. My biggest gripe, though, is the book’s frequent use of punctuated dramatic pauses, which work rather…like this! And after a few repetitions, they become…extremely annoying! Well, you get the point.

Still, I urge you to read this book for the force of its central character, and the drama and the delight of discovery that he transmitted throughout his life. Read it, as well, for glimpses of the deep connections in symmetry between phase transitions and polymer molecules, and between superconducting states and milky nematic liquid crystals. But most of all, read it to be reminded that physics is the science that knows no frontiers, and to be taken to some high and wild places by a fearless guide who is missed by all of us who knew him.