Janne Poranen is co-founder and executive chair of Finnish start-up Spinnova, which spins wood pulp into sustainable fibre for clothes. He talks to Julianna Photopoulos about falling into a physics career and using cellulose technology to help make the fashion industry more sustainable

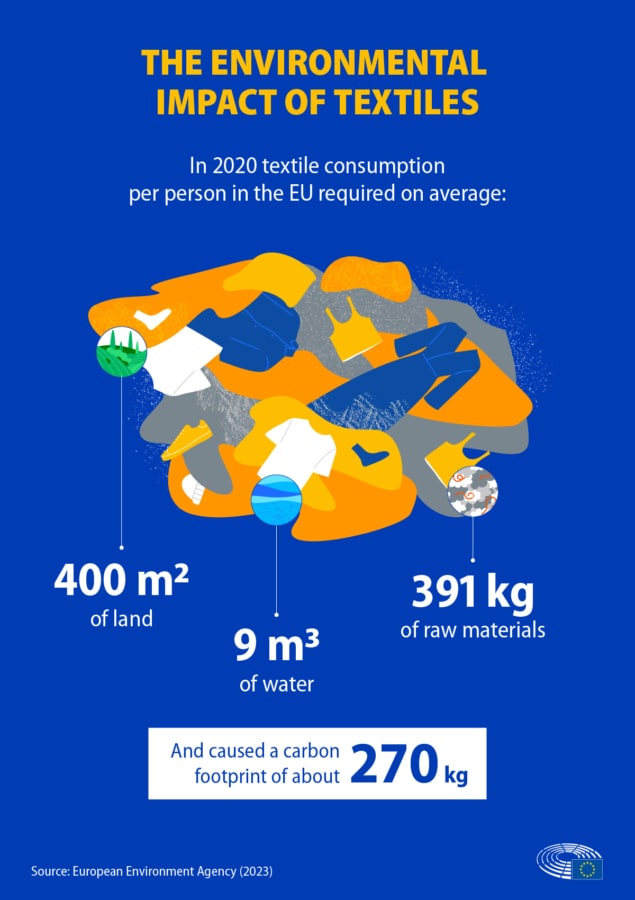

You might be somewhat shocked to know that, according to a recent European Union (EU) study, worldwide fashion and clothing is responsible for 10% of global CO₂ emissions – that’s more than international flights and maritime shipping combined. It’s probably not something you think about when you pull on your jeans in the morning, but your clothes come with a significant environmental cost.

Indeed, estimates suggest that manufacturing that one pair of jeans emits around 16.2 kilograms of CO₂ – and yet, nearly 2625 kg of clothing becomes waste every second. Additionally, it takes about 10,000–20,000 litres of water to make 1 kg of cotton – roughly the amount needed to produce one t-shirt and a pair of jeans – and the chemicals used for dyeing and finishing the product further contribute to water pollution.

While most of us might be concerned by these worrying figures, Janne Poranen – a physicist at the Technical Research Centre of Finland (VTT) at the time – decided to do something about it in 2014. As head of biomaterials at VTT – the largest Finnish research and technology organization – he couldn’t help but wonder if it was possible to create more sustainable textiles; ones made with minimal water, without the use of polluting chemicals and with negligible CO2 emissions. With this in mind, he proposed a spin-off company, together with his VTT team leader, physicist Juha Salmela. The duo co-founded Spinnova, a company that today transforms cellulose from Forest Stewardship Council (FSC)-certified wood into textile fibre without using any chemicals.

Spin a yarn

The spark of the idea for the technology came in 2009, when Salmela heard a talk by Fritz Vollrath, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Oxford, in which he outlined the similarities between spider silk and nanocellulose. At the time, Salmela’s team was focused on how cellulose pulp flows, and Salmela thought, “what if wood fibre could be spun into textile fibre in a similar way to the natural process of a spider’s web?”

Indeed, Spinnova was able to mechanically process wood pulp into microscale fibres, which are aligned in a chain and drawn out at high pressure through a tiny nozzle into a cotton-like thread. The fibres are then dried and collected, ready to be spun into yarn. “All artificial cellulose fibres are based on dissolving processes – we do not do any dissolving of the raw material,” explains Poranen.

These new fibres use 99.5% less water and 74% less CO₂ emissions than conventional cotton, and are both recyclable and biodegradable. In addition to being chemical-free, Spinnova fibres are also free of microplastics. By 2033 the company estimates that its fibres could replace 4% of the world’s €44bn cotton supply, putting less strain on the environment and potentially improving safety for textile workers.

It took Poranen and Salmela eight years from setting up the company to commercialization, and today they have 37 international patents and more than 40 patents pending. Poranen believes that their physics background has set them up well for this long-yet-exciting journey towards solving the fashion industry’s dependence on environmentally harmful fabrics.

Going with the flow

Poranen’s pathway as a physicist began in unusual circumstances. He had just finished his compulsory military service in Finland, when he came home to find a letter from one of the many universities he had applied to. It said Poranen could study physics without taking an entrance exam because he had got such good marks at high school. Poranen duly started at the University of Jyväskylä in Finland, from which he graduated in 1997, along with a teaching degree. “I was – and still am – going with the flow,” he says.

Poranen had initially planned to become a physics teacher, but after really enjoying his Masters in flow dynamics and rheology at the same university, in conjunction with the pulp and paper company Valmet, he decided to continue with a PhD. “At the beginning I didn’t have any plans to do a PhD because I thought physics was way too hard for me,” says Poranen. “I was selected for a graduate programme that had close cooperation between industry and the university, and this was where I looked at what kind of rheological properties are needed to get certain kinds of paper-coating applications.”

Poranen also worked at VTT as a research scientist during his PhD, and before completing it in 2001, ended up working as an exchange researcher for more than a year with Douglas Bousfield at the University of Maine in the US. There, Poranen learnt more about developing simplified models to represent industrial processes, such as paper coating and printing, and how to verify these with experiments. When paper fibres are mechanically treated, fine-scale fibrils called cellulose nanofibrils (CNF) are generated. As Poranen learnt, these can be used in various applications such as coating, paints and medical devices. Later, Bousfield ended up as Poranen’s PhD examiner.

Early on, Poranen knew that he preferred applied physics, and that a traditional academic career was not the path for him. After his PhD, he continued as a research scientist at VTT, but soon took on managerial roles in the forestry sector, which essentially involves overseeing products, activities and the management of forests and woodlands – be it timber, wildlife studies, biodiversity or recreation. Poranen covered a variety of jobs, from building new customer consortiums to managing R&D studies from six to eight teams as a technology manager. “Our team’s main achievement was to develop VTT’s research in the forest sector into globally leading research,” says Poranen, who remained in that position for nearly eight years before moving to work on VTT’s research in biomaterials. He became head of this department, managing six research teams and 120 employees.

In 2011 VTT was selecting its future leaders to attend a year-long virtual business-management and innovation programme at IMD Business School in Lausanne. Poranen was delighted to be one of the few who was chosen to attend, from a pool of more than 3000 researchers. Indeed, he believes it was this programme that gave him the confidence to set up Spinnova. This was where he “learned about leadership, management and strategy, along with helping me to look at the bigger picture. And it made me – someone from the central Finland forest – bold enough to come up with radical innovations.”

Spinning out

Although Poranen had been head of biomaterials at VTT for around a year, he knew in his gut that the technology being developed by Salmela’s team was revolutionary. “It was the best innovation that I had ever seen coming out of the pulp and paper sector,” he says. While Poranen was not personally involved in the details of the technology, he found that “with my physics background, it was easy for me to understand that this was a radical innovation that had to be taken to industrial scale”.

Poranen had met Salmela during his undergraduate studies in physics. By combining their expertise, he believed that together they could move their patented idea of producing textile fibre out of cellulose forward, and transform the fashion industry. Three key researchers from Salmela’s team – two physicists and one engineer – joined them from the start, making it easier for the company to take off. “We had all the competence we needed but had to come up with ways to scale the technology from the lab; there was a lot of trial and error,” says Poranen. Today, Salmela is Spinnova’s chief technology officer.

At first, Spinnova looked at making filament yarn from paper–pulp fibres, but ditched that for sustainable microfibrillated cellulose (often referred to as nanocellulose) two years later, after buying the intellectual property from VTT. “That was a big decision,” says Poranen. Despite changing roles – from head of biomaterials at VTT to chief executive of Spinnova (a position he held until 2022) – not much changed, as he continued to be involved with the strategy and funding. But Poranen acknowledges that working for his own company made his responsibilities and workload larger. “I was working 24/7 for the last seven years,” says Poranen.

But all his hard work paid off. In 2019 Spinnova finally started a pilot-scale production facility in Jyväskylä, Finland. Several renowned clothing brands such as H&M, Adidas and Marimekko had already taken an interest in the fibre and started working with Spinnova’s research and development. Its initial production facility was just a basement, but “in 2021 we were able to convince ourselves and our partners, Brazil-based Suzano – the world’s largest hardwood pulp producer – that we were ready to scale this up into the commercial level,” he says, adding that the process only makes “something like one tiny hair” so it has been a challenge to scale up.

As it happens, at the end of May this year, the first commercial facility producing SPINNOVA® fibre was launched. Operated by Woodspin – a joint venture between Spinnova and Suzano – the aim is to annually produce 1000 tonnes of its textile fibre from responsibly grown eucalyptus trees. “Spinnova’s patented fibre production process doesn’t require any harmful chemicals or dissolving, nor does it generate waste or microplastics,” explains Salmela. He adds that the process “has a 74% smaller life cycle carbon footprint and uses 99.5% less water compared to conventional cotton production. The result is a natural, cotton-like textile fibre that meets the rigorous environmental and performance demands of brands and consumers alike – and, through facilities such as this one, can now be produced at scale.”

Scaling globally

Although Poranen is no longer responsible for Spinnova on an operational level, he is excited that the company has finally made it to commercial scale. In his new role as executive chairperson of Spinnova’s board, he can now step back and look at the company’s long-term future. “As CEO I was basically responsible for everything; everybody is always coming back to you, asking if this or that is okay to do or how to move forward, and so on,” he explains. “You are practically running the whole company and it is an emotional rollercoaster because one day the company can be in a bad position but fine the next.”

Poranen’s goal is for Spinnova to become a world-leading sustainable textile fibre company. “The big dream is that we are able to scale it up globally,” he says. For Poranen, readily available wood pulp is Spinnova’s best bet for achieving mass scale. But, in principle, Spinnova’s technology can use any type of cellulose – be it agricultural or biowaste-based cellulose, or leather and textile waste – to produce its fibre. In fact, as of September this year, Spinnova partnered with Swedish textile-recycling company Renewcell to spin textile-waste-based fibre into new, bio-based textile fibre. Renewcell’s technology allows it to recycle textile waste such as cotton and viscose into a biodegradable pulp product called “Circulose”, which can then be used to produce new fibre. So far, Circulose has only been used to create artificial cellulosic fibres, such as viscose. By partnering with Spinnova, Circulose pulp can now be used to fabricate bio-based textile fibre, without the use of any harmful chemicals in the fibre-spinning process. Indeed, Spinnova has already produced the first batches for yarn and fabric using 100% Circulose, and made the first prototypes from a blend of cotton and Circulose-based Spinnova fibre. Spinnova estimates that the first consumer products will be available by the end of 2024.

Despite the challenges, Poranen believes that his physics expertise has prepared him for everything. “Physics itself is extremely tough, but you learn how to solve almost impossible problems,” he says. “The biggest lesson physics has taught me is to not be afraid of whatever challenges come your way and to keep moving forward.”