I Died For Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science

Marjorie Senechal

2012 Oxford University Press £22.50/$34.95hb 312pp

In March this year, the author of a well-regarded science website was revealed to be – wait for it – a woman. The identification of Elise Andrew as the founder of the provocatively titled Facebook page “I Fucking Love Science” was greeted with astonishment, tinged in some cases with outrage. This anecdote says much about the general reaction to women in science: even in 2013, it is still not taken as a given that women may be good at science and enjoy it. Imagine how hard it must have been 80 years ago, when Dorothy Wrinch was struggling to make a name for herself as a mathematician working at the interface with biology.

Wrinch (1894–1976) was educated at Girton College, Cambridge at a time when women still had to ask permission to attend lectures that were given by men for the university’s “real” students, i.e. the men. Over the years, she variously worked in Cambridge, London and Oxford (always in short-term posts with insecure funding), tackling philosophical problems with Bertrand Russell and other giants of the day and considering questions related to symmetry and beauty in nature. Ultimately, she became interested in protein structures. At this point, she ran up against Linus Pauling, to her great detriment, and she died in relative obscurity.

Does Wrinch’s losing encounter with Pauling explain why she is largely forgotten today? I had certainly never heard of her before I was sent this new biography, I Died For Beauty (the title comes from an Emily Dickinson poem). Or is it because she was a woman – and, as far as I can judge from the book, a cussed and difficult woman at that – at a time when they weren’t fully accepted into the scientific fold? The book left me uncertain as to the answer to those questions, although it does describe some rather interesting episodes in the history of science.

During Wrinch’s heyday of the 1930s to 1950s, there was huge interest in crystals and lattices as many scientists across a variety of disciplines tried to work out how these complex crystal structures, in particular proteins such as insulin and haemoglobin, could be inferred from X-ray diffraction patterns. Wrinch was part of this tribe of scientists. At the time, of course, the computers we today take for granted did not exist; indeed, the term “computers”, in the early days, referred to people who worked out complicated calculations to produce, for instance, tables of functions. These calculations were long and difficult. Hence, even had the theories of the time been robust, moving from the observed diffraction pattern (which necessarily lacks information on the phase of the contributing waves) to the underlying structure seemed like an intractable problem; progress on both theoretical and experimental fronts was slow.

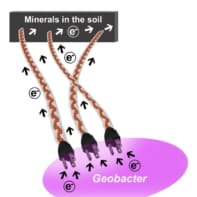

Undoubtedly, Wrinch made significant contributions to the field, particularly in her fairly late work Fourier Transforms and Structure Factors (1946), in which she laid down in detail much of the field’s mathematical basis. But it was her model for protein structure itself that led to many personal attacks and damage. Wrinch was convinced that proteins were not long chains of molecules (described at the time as resembling Christmas tree lights). Instead, she believed they were an indefinite fabric of rings, which she termed “cyclols” (see “Contentious” figure). This idea was initially compatible with the limited evidence, but she clung to it long after new data made it scientifically untenable, and possibly right up to her death.

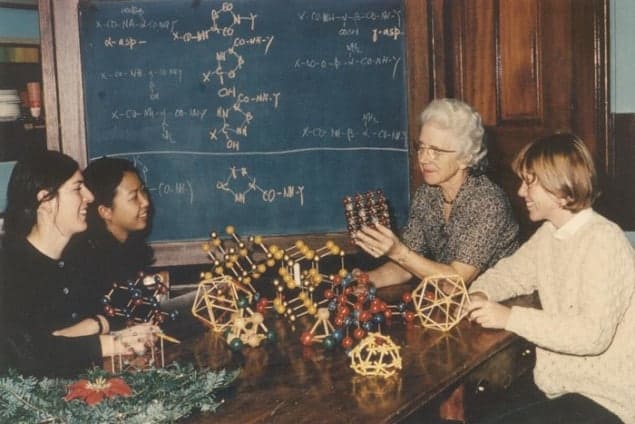

To begin with, she had many influential supporters, including the chemical physicist Irving Langmuir. However, her inflexible attitude as the counter-evidence built up did nothing for her reputation, and it seems that she was always something of a divisive character. The book’s author, Marjorie Senechal, knows this firsthand: she describes herself as a mathematical crystallographer, and towards the end of Wrinch’s life, when both women were at Smith College in Massachusetts, they worked together informally. Senechal draws on this personal experience in the book, but she also had access to extensive diaries kept by senior members of the Rockefeller Trust, whose role it apparently was to travel around asking senior scientists to comment on colleagues whose work the trust might fund. Quotations taken from these diaries include the statement that “[Wrinch] is in bad favour in many quarters in England” and “P said flatly that he has always said she is a fool but that B insists she is only mad”. And these quotes actually precede the fracas over Wrinch’s cyclol model, where she clashed so painfully with Pauling.

Senechal chooses to make the chapter on Wrinch’s exchanges with Pauling into the skeleton of an opera, outlining the acts though not fleshing out the libretto in full. As she puts it, “Dorothy Wrinch’s epic battle with Pauling is the stuff of opera. There is no other way to tell it. Two brilliant, arrogant, competitive antagonists with a flair for publicity and a touch of the devious! And what a plot!” These few sentences demonstrate the flavour of the book. Senechal’s style is personal and staccato, and throughout the book, her own interactions, interests and driving forces creep in, leading to multiple digressions in chronology and topic. This can be confusing, although the anecdotes are also illuminating and often intriguing. I learnt, for example, about diverse background issues and individuals ranging from D’Arcy Thompson to mineralogists and members of the Smith College faculty. But at the end of the book I felt I had not grasped the essence of Wrinch herself.

Clearly, she was a multi-faceted and hugely original scientist. She was also struggling to cross the divide between many disciplines, some of which, such as molecular biology, were at the time only just coming into being. But was she a flawed genius whose central thesis about cyclols was wrong, so the rest of her work, important though it was, has been allowed to sink into obscurity? Maybe – but then, Pauling himself made a glaring mistake late in his life, yet his reputation has survived pretty well intact. One might reasonably conclude that Wrinch’s gender was a factor in the way she was treated. But does this make her a brilliant woman in science, ahead of her time, whose strong personality led her to dare to challenge a patriarchal society and come off worst? Or was she just a run-of-the-mill scientist with an awkward character and a colourful personal life, whose vanishing from the list of the period’s “great and good” is justified? I suspect Senechal herself is ambivalent on these questions, but it is a pity that she doesn’t give readers enough solid information to allow us to form our own firm judgement.