Physicists in the US and Japan have seen the best evidence to date for a new form of superconductivity. Ying Liu and co-workers at Pennsylvania State University and Kyoto University have observed "odd-parity" superconductivity in strontium ruthenate. Although first predicted by theorists some 40 years ago, all previous evidence for this new superconducting state had been indirect (K D Nelson et al. 2004 Science 306 1151).

A common feature of all superconductors – both the low-temperature and high-temperature varieties – is that electrons in the material somehow overcome their mutual electrostatic repulsion to form Cooper pairs below a certain transition temperature. These pairs can then condense into a single quantum state and move without electrical resistance.

In a low-temperature superconductor the total orbital angular momentum of the two electrons in a Cooper pair is zero – a so-called s-wave state. By contrast the Cooper pairs in a high-temperature superconductor exist in a d-wave state with L=2, where L is the total orbital angular momentum. The latest results confirm that the Cooper pairs in strontium ruthenate form a p-wave state with L=1. States with p-wave symmetry are also formed when liquid helium-3 becomes a superfluid.

According to the laws of quantum mechanics, the wave function of a pair of electrons must change sign when the electrons are exchanged. This means that only certain combinations of orbital and spin angular momentum are possible. If the L is an even number, then the two spins must point in opposite directions to form a “spin-singlet” or “even-parity” state. However, if L is an odd number, the spins must point in the same direction in a “spin-triplet” or “odd-parity” state. Although evidence for odd-parity superconductivity has been seen in strontium ruthenate before, other explanations are also possible.

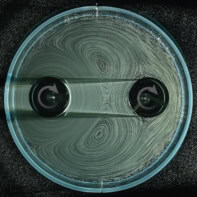

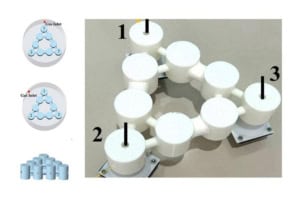

Liu and colleagues connected a sample of superconducting strontium ruthenate to a conventional superconductor through two Josephson junctions. Cooper pairs are able to tunnel through the junctions in both directions and the entire ensemble is known as a superconducting quantum-interference device (SQUID). By measuring the current through the SQUID as a function of an applied magnetic field, the Penn State-Kyoto team was able to confirm that the Cooper-pair currents passing through each junction had interfered destructively. This is only possible if the Cooper pairs in the strontium ruthenate are in a spin-triplet state.

“Our work completes a 40 year quest to find an odd-parity superconductor,” Liu told PhysicsWeb. “We now have a new playground to study such superconductors, which may lead to further discoveries.”