The average greenhouse-gas emissions from the entire life cycle of shale and other “light tight” oils are two-thirds of those for heavy oil and bitumen resources, researchers in the US have found.

The result comes alongside an appeal to policy makers that we should be concerned not just with minimizing our consumption of oil, but on the type of oil that we do use, in order to reduce climate change.

“The main attention is on reducing oil consumption – which is [the] right direction,” said Mohammad Masnadi of Stanford University. “But … policy makers should pay equivalent attention to crude oil type and the corresponding greenhouse-gas emissions for designing future policies and strategies.”

Oils come in various forms, but broadly speaking there are three types: conventional crude, light-tight oil from low-permeability rocks such as shale, or particularly viscous heavy oil and bitumen from sands. In the early part of this century, investment in light-tight oil and heavy oil/bitumen rose dramatically as oil prices boomed.

That’s good news for meeting demand, but less good for the climate. Three years ago, Christophe McGlade and Paul Ekins at University College London in the UK estimated that to keep global temperature rise below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels, in accordance with the Paris agreement, humanity must leave over one-third of current oil reserves unburned.

Like most other climate researchers, Masnadi and colleagues believe that policy makers need to reduce our oil consumption as much as possible. But that is not enough, they say: given the excess of resources, we also need to choose wisely which oils we burn.

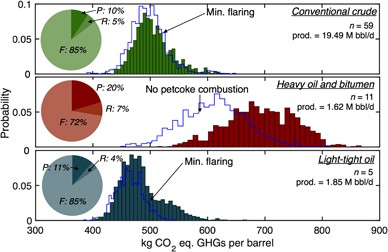

To assess the wisest choices, the researchers developed three oil life-cycle assessment tools to individually compute the greenhouse-gas emissions from oil extraction, oil refinement and final combustion or other usage. After integrating the tools into a single “well to wheel” tool, they applied it to data on 75 different oil fields worldwide.

The average (median) life-cycle emissions for light-tight oils were two-thirds of those for heavy oil/bitumen, a difference of some 200 kg of carbon dioxide equivalent per barrel. Opting for lighter oils could be a climate-change mitigation opportunity worth 10–50 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2050, the team found.

“We know that we have abundant resources to address the supply,” said Masnadi. “Therefore, we need to select the crude types strategically in order to mitigate as much greenhouse-gas emissions as possible.”

Masnadi and colleagues’ work on this is not over yet. They want to expand their analysis from 75 sites to all the world’s oil fields, and understand the global climate implications. Then they want to connect the emissions information to cost indices, to explore the specific mitigation policies that would have most impact.

The study is published in Environmental Research Letters (ERL).

- This article was updated on 11 December 2018 to correct the difference in emissions from “one and a half times lower” to “two-thirds”.