Philip Ball reviews The Dialogues: Conversations About the Nature of the Universe by Clifford V Johnson

The dialogue as a method of discourse on philosophical matters has fallen out of favour these days, but that’s a recent development. As Frank Wilczek points out in his introduction to physicist Clifford Johnson’s The Dialogues: Conversations About the Nature of the Universe, the format was preferred by Plato (who often included his teacher Socrates as a protagonist), and was also chosen by Galileo for his epoch-making Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems. Although Galileo’s tract was a self-conscious post-Renaissance echo of the classical form, framing a rational explanation of the world as a discussion between an experienced teacher and an eager but naïve pupil has been popular throughout the history of Western thought. English philosopher Adelard of Bath used it for his Questiones Naturales in the 12th century, one of the books that belies the myth of an irrational Middle Ages. Jane Marcet’s 1805 book, Conversations in Chemistry, in which a teacher-governess instructs her two female pupils, not only challenged the notion that science was a male pursuit but also proved a pivotal influence on the young Michael Faraday, who never forgot the debt.

The appeal of the dialogue form is easy to appreciate. It allows multiple points of view to be explored and interrogated. This is the approach Galileo championed to debate the merits of the Ptolemaic/Aristotelian and Copernican world views, although his bias is painfully clear – Simplicio, who defends the Ptolemaic model with the blinkered mulishness that his name implies, was suspected by Galileo’s opponents of being a lampoon on Pope Urban. And the pupil, whether in Adelard or Marcet, represents the reader, expressing confusion, incredulity or enthusiasm in the face of the teacher’s calm authority.

The ancient and the modern formats turn out to be made for each other

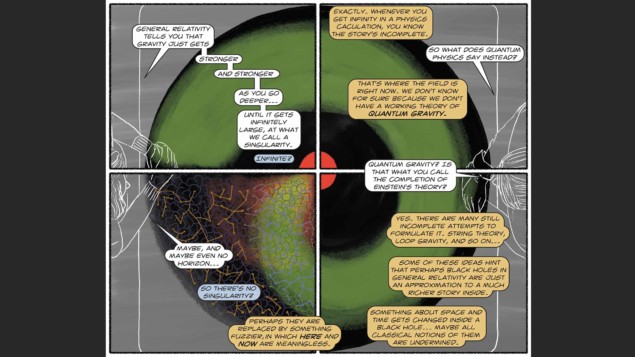

In The Dialogues, Johnson demonstrates how useful and versatile this novice/expert structure can be in conveying complex scientific knowledge, in the form of 11 conversations, on topics ranging from inflation and relativity to simple discussions of experimentation and geometry. But he reinvents the dialogue for our times as a graphic novel. It’s an inspired choice, for the ancient and the modern formats turn out to be made for each other. Not only does the question and answer structure lend itself to dramatization, but the interaction comes alive when the characters are situated in time and space. In the short narratives of Johnson’s book, they meet at a costume party in a natural history museum, or they are siblings at home working out how to conduct a simple experiment to find the answer to a question, or they are two scientific colleagues chatting over a coffee, and so on.

Using the comic-book approach to talk about science isn’t new in itself. Mathematician and illustrator Larry Gonick was one of the first to bring the cartoon to science – most famously in his multi-volume The Cartoon History of the Universe, begun in the late 1970s, and also in his regular “Science Classics” strip for Discover magazine. Sydney Padua’s The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage, first conceived in 2009, offered a hugely popular, knockabout version of the “invention of the computer” by Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage in the 19th century. These and other explorations of scientific themes in comic form were, however, more humour-driven than Johnson’s book, which aims for something more sober and adult-oriented in the tradition of the “mature” graphic novel, the genesis of which is often traced to Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1980–1991), a story of the Holocaust.

Johnson says he was also inspired to use this approach to science popularization by the realization that it is perfectly suited to the material. While mostly his stories adhere to a realist pictorial style, from time to time they mutate into the diagrammatic. In The Dialogues, characters assemble giant pieces of a jigsaw puzzle bearing the fundamental equations of physical law: we segue from a sidewalk to a vista of the deep universe; a character unfolds a protoplanetary disc from between her outstretched hands. This is perhaps the most successful feature of the project, and it makes the traditional illustrations of popular-science books look rather dry and creaky.

The visual innovations are all the more impressive given that Johnson, a specialist on string theory and general relativity at the University of Southern California, taught himself illustration from scratch. It’s easy to discern his passion for the classic comic-book tradition in his use of cinematic perspectives – the close-ups, panning shots and unusual viewing angles – which no doubt also benefitted from Johnson’s experiences as a scientific consultant for Marvel movies such as Thor: Ragnarok. In this regard, the book is just the latest instalment of Johnson’s extensive outreach activities in physics.

Occasionally the ambition of The Dialogues somewhat exceeds the delivery. Even the “naïve” characters tend to have a rather firmer grasp of physics than the average general reader is likely to, and while a readiness to delve into actual equations is a refreshing departure from the orthodoxy of science popularization, it may well prove a step too far once characters start saying things like “So we write their field as Ψ, and working with A and V allows us to write an equation describing how electrons interact with E and B fields”. As that quote suggests, the speech is also rather stilted at times, the visual friendliness not always quite managing to compensate for a lecture-like tone.

But this is, after all, an experiment, with room still for refinement. The Dialogues presents a new and exciting way to communicate sophisticated ideas, full of potential. I can’t help fantasizing now about seeing papers in Physical Review written this way – a thought that will no doubt horrify some, just as the first serious graphic novels horrified folks convinced that the only “true” literature can be words on paper.

- 2017 MIT Press 246pp £24hb