With the world economy struggling, physics graduates might be tempted to ride out the recession by doing a PhD or postdoctoral research. But as Margaret Harris reports, the academic sector has its own career problems

Barnaby Rowe is a 29-year-old postdoctoral researcher at University College London. An astrophysicist by training, he came to London after a 19-month stint at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, having previously done a two-year-long postdoc at the Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris in France. By the time his contract runs out in 2014, he will have spent nearly seven years in academia, chasing job opportunities and research funding across three countries and two continents. But his current academic post, Rowe has decided, will be his last. “Some of my colleagues laugh about this, because I’ve been saying it for a long time,” he explains. “But this time I think I’ll do it.”

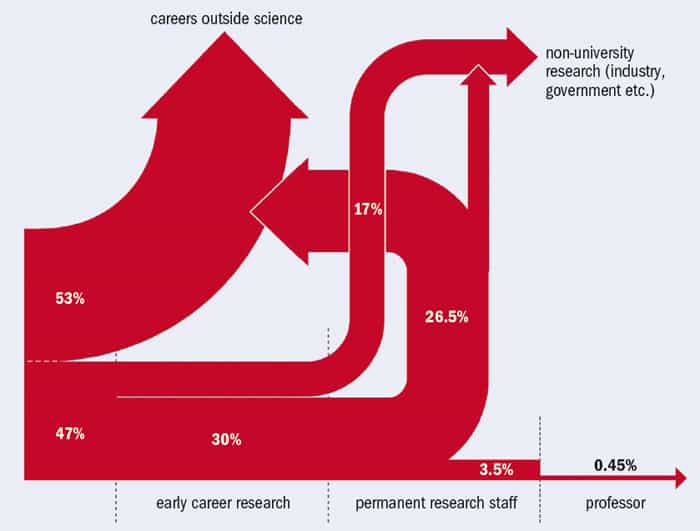

Rowe’s story is not unusual. Statistics suggest that the vast majority of people who complete science PhDs will never obtain a permanent academic post. This is vividly illustrated in a diagram published in 2010 by the Royal Society as part of a report on the future of scientific careers in the UK (figure 1). Drawing on data from various UK sources, the diagram follows a “typical academic career” through a series of post-PhD transition points, when large numbers of people leave the university environment for careers in, say, government or industrial research. These data show that less than 0.5% of science PhD students will ever become full professors, while just 3.5% will obtain lower-ranking permanent positions as research staff at universities.

For physicists, that 3.5% figure is probably a little low. Slightly older data collected by the Institute of Physics and the US National Science Foundation suggest that the fraction of physics PhD students who obtain permanent academic jobs has historically hovered between 10 and 20%. Yet even this higher number still indicates a yawning gap between the aspirations of early-career physicists and the realities of the academic job market. Indeed, according to an August 2012 survey carried out by the American Institute of Physics (AIP), nearly half (46%) of new physics PhD students at US institutions want to work in a university. The next most popular career plan among those surveyed, attracting 18% of responses, was “unsure”.

The mass departure of PhD-level physicists from academia is not, in itself, a bad thing – either for society or for individuals. “The knowledge and skills developed [in a physics PhD] are first rate, and can be applied across many disciplines to a huge set of potential problems,” notes Steve Hsu, a physicist and vice-president for research and graduate studies at Michigan State University in the US. Jobs in finance and technology, he points out, are usually better paid and more stable than the series of temporary posts that has become the norm for postdocs and other early-career researchers (ECRs). As a result, Hsu says, he often advises PhD students who have an interest in applied research to seek careers in industry, rather than academia.

But for many, the decision to leave the ivory tower is not entirely voluntary, and some postdocs have expressed concerns about their lack of preparation for alternative careers. One person interviewed for this article noted that although most postdocs do make contingency plans, “having a plan B can be seen as lacking commitment to an academic career”, and might therefore harm their chances of obtaining that elusive permanent post. There are also indications that a career structure built on a series of short-term contracts is hurting science as a whole, by depriving it of talented people who leave for reasons that have nothing to do with aptitude or enthusiasm.

All of these factors – the shortage of permanent academic posts, the gap between expectations and reality, the anxieties about training and the fact that “success” depends on much more than talent and hard work – have prompted a groundswell of concern for ECRs. In July an article in the Washington Post about the lack of career opportunities for PhD-qualified scientists in the US attracted more than 3500 comments from readers, many of whom shared personal experiences of the tough academic job market. Meanwhile, in the UK, a consultation exercise carried out in mid-2011 by the pressure group Science is Vital received nearly 700 responses from scientists troubled about the structure of academic careers. Their answers to a questionnaire indicated widespread dissatisfaction about the prevalence of short-term contracts, the perceived or actual need to emigrate or relocate for jobs, and the impact of mobility on families and relationships (see “On the move” below). Some of those who responded – including senior scientists as well as ECRs – compared academic research to a pyramid scheme that produces a tiny handful of “winners” and a huge number of “losers” in the scramble for permanent posts.

A paradoxical situation?

When the American baseball player Yogi Berra was asked why he no longer frequented a particular restaurant, he replied, “Nobody goes there anymore. It’s too crowded.” In some ways, the situation for ECRs seems to echo Berra’s words. In essence, the sheer number of junior researchers limits their long-term career prospects, but this does not seem to be stopping people from joining the queue. To put it bluntly, if career progression is so poor, why does the field remain so competitive?

One answer is that an academic career holds many significant attractions. “What I love about working an academia is the independence,” says Sarah Kendrew, an astrophysics postdoc at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. “Not just in terms of working hours and not having to conform to some corporate image, but independence of thought. In research, we’re not just ‘allowed’ to have our own opinions – we’re actively encouraged to develop and pursue our own ideas.” In comparison with other posts she has held – including an engineering job and an internship in a scientific press office – the independence of academia is “an amazing luxury”.

Others echo her views. “The best thing about being a postdoc is having the freedom to do something you are passionate about,” says Aimee McNamara, a medical-physics researcher at the University of Sydney in Australia. “Even if you are employed for a particular project, you get the freedom to pursue your own research interests as well. Not many jobs in the world offer that.”

But there are also some less pleasant factors contributing to the crowded postdoc pool. One is the economy. Many employers that traditionally offered well-paid research work outside a university environment have shed jobs in recent years, limiting alternative career options. For example, a report carried out in June by the scientific data firm Battelle found that the number of biotech jobs in the US shrank by 1.4% between 2007 and 2011, while employment in aerospace-related jobs fell by 2.4%. Both figures compare favourably with the 6.9% drop across the US private sector as a whole, yet there are signs that cuts in key industries have hit some early-career scientists hard. Indeed, the American Chemical Society found that only 38% of new chemistry PhDs who responded to its annual careers survey had found permanent non-academic jobs since graduating in 2011 – the lowest fraction for seven years. The fraction employed as postdocs, in contrast, went up slightly, rising from 45% in 2010 to 47% in 2011.

Another factor boosting the number of postdocs relative to the number of permanent jobs concerns the “pyramid” structure of scientific funding. At entry level, funding for PhD studentships, research assistantships and postdoctoral fellowships is often relatively plentiful. At more senior levels, however, funding tapers off and competition becomes much more intense. According to Athene Donald, a condensed-matter physicist at the University of Cambridge who often discusses career issues on her personal blog, the “pyramid” problem is particularly acute for biomedical researchers. “So much money has been thrown at ‘let’s cure cancer’ or whatever that there are lots of entry-level positions for students and postdocs that don’t go anywhere,” she told Physics World. “And they will never go anywhere because there aren’t enough jobs higher up.”

Advice and training

Funding for physics research is not quite as pyramidal as it is in biomedicine, chiefly because there are fewer entry-level posts available. However, physicists are not immune to other factors driving the postdoc boom. One of these is a lack of advice about possible alternative careers. A recent paper by researchers in the US examined how “adviser encouragement” affects career preferences among PhD students (H Sauermann and M Roach PLoS ONE 7 e36307). They found that while academic physicists, as a group, generally encourage their students to seek university-based employment, they tend to adopt a more neutral or discouraging stance towards non-academic work (figure 2a). This was the case even though the students themselves became slightly less interested in physics research and teaching over the course of their PhDs (figure 2b). According to a 2010 report by the UK research organization Vitae, physicists may also be at a disadvantage in their knowledge of alternative careers. The report found that only 24% of physical-science students had a permanent job directly before beginning their PhDs, compared with 57% of students in the biomedical sciences and 49% of biologists.

Donald acknowledges that senior academics are partly to blame for the shortage of advice, especially when they give the impression that students who leave academia have failed or “wasted” their scientific training. “That is a terrible message [but] it’s pretty pervasive,” she says. “I think it happens because professors love what they do and they can’t imagine how anyone wouldn’t want to do it.” However, she adds, the lack of advice can also stem from simple ignorance. “I think there’s a real problem with principal investigators who have only ever been in academia not knowing what the job situation is like for people with particular qualifications,” she says. “I’m not good at knowing what – other than academia – is out there.” To fill this gap, Donald says she often refers students to Cambridge’s careers service, which employs a dedicated adviser for postdocs in the physical sciences.

As well as offering better advice, Hsu believes that universities should also be offering more training to ECRs. “We could do more to prepare students specifically for careers outside physics by requiring them to take courses in, for example, computer science and management,” he suggests. Exposing students to the career experiences of their predecessors who left academia would help, Hsu says.

Tending the academic dream

There is just one problem with providing better training and advice on non-academic careers: many PhD students and ECRs are not interested, or feel they do not have the time to investigate their options. “I really don’t have a back-up plan,” says Alan Duffy, an astrophysics postdoc at the University of Melbourne, Australia. “It’s something that I often find myself briefly thinking about, but then other tasks in my day demand my attention and it’s set aside.” David Nataf, an astronomy PhD student at Ohio State University, agrees. “My PhD training was tightly focused on academic careers, but that’s what I chose,” he says. “Had I been planning to opt out, I would have asked for more teaching duties, or taken some programming and statistics courses…[but] I hope to continue in academia and specifically in research for a very long time.”

Duffy and Nataf are not alone. In an informal poll carried out on Physics World‘s Facebook page last month, respondents were asked to pick which action would be most helpful to physics postdocs. Only 17% chose options related to training or advice on non-academic jobs. The overwhelming favourite, with 73% of the vote, was longer-term contracts – something that would help keep more physicists in academic research, rather than helping them succeed outside it.

Rowe, however, thinks that longer-term contracts would be a major improvement even for physicists who, like him, decide to leave academia. “I can’t help but think that the annual-to-every-two-years round of writing applications and proposals to stave off your pre-determined unemployment is bad for productivity,” he says. Fewer, longer contracts for postdocs would also benefit scientific projects that have long lifetimes compared with a typical two- or three-year contract, he adds.

Intriguingly, some recent research supports the idea that longer-term contracts would be better for science. After analysing the productivity of 300 physicists, a group of complexity theorists in Italy and the US found that short-term contracts can “amplify the effects of competition and uncertainty” and thus make academic careers “more vulnerable to early termination, not necessarily due to lack of individual talent and persistence, but because of random negative production shocks” (Petersen et al. PNAS 109 5213). The theorists also found evidence of a “rich get richer” system, in which an initial bit of luck – publishing a single outstanding paper, for example – can mushroom into a career-long advantage over less fortunate (but no less talented) colleagues.

Changing the pattern

In its report on science careers in the UK, Science is Vital takes the idea of longer postdoc contracts to its logical conclusion by recommending the creation of permanent postdoc-level jobs. Kendrew agrees that this would be a good idea. “A lot of postdocs are involved in what I could describe as ‘infrastructure work’,” she explains, citing software development, data management and instrument building as examples. “These people often get little credit for their contribution, and as they don’t publish as many papers…they fall by the wayside.”

Others, however, are more sceptical. “I can see the attraction, and I know a few people for whom a permanent postdoc would be ideal,” says Donald. “But if you have a mature team – a professor, a couple of senior lieutenants and a long-term postdoc – they will get into a pattern where it’s terribly hard for them to do lateral thinking. Whereas if a new person comes in and asks an incredibly naive question, they can kick-start enquiry in a different way.”

One alternative would be to reduce competition for permanent jobs by limiting the number of PhDs and postdocs being offered. Among those advocating this strategy is Jonathan Katz, a physicist at Washington University in St Louis, Missouri. In 1999 Katz posted an essay on his website entitled “Don’t become a scientist!” In it, he outlined reasons not to pursue an academic career – including poor job prospects – and he told Physics World that his advice was still applicable today.

But there are problems with this approach too, Rowe argues. “I got a good degree, but I think there were people who had less aptitude as undergraduates who have subsequently shown more aptitude as researchers,” he says. “So I would be wary about throttling back the numbers of PhD students.” A better strategy, he suggests, would be to make sure that PhD students know they have other options if they choose not to stay in academia. Above all, he adds, they should not feel like their years as researchers were a waste of time.

That sentiment is echoed by Phillip Helbig, a former research assistant who now works as a systems analyst at the stock exchange in Frankfurt, Germany. When asked via e-mail whether his stint as a full-time academic researcher was “useful” to him, his reply began with the words “Define ‘useful’!” and the opening lines of Charles Dickens’ novel A Tale of Two Cities (“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…”). “I don’t think it was useful in terms of preparing me for other work,” he continued. “This aspect is exaggerated. Doing a degree that requires a thesis and programming experience is good for many things, [but] anything beyond that is not helpful in any technical sense, and might be counterproductive among employers who prefer hiring younger people.” Still, he wrote, “I am extremely glad that I spent the time I did in academia. It was worth it even if I didn’t stay.”

On the move

“When I started out with my PhD, the need to move around to pursue a career in science was actually appealing to me,” says Aimee McNamara, a South Africa-born medical physicist who is currently doing a postdoc at the University of Sydney in Australia. “I liked the idea of experiencing different research environments as well as different cultures, and I still believe it’s a very important thing to experience as a scientist.”

Moving from one location to another is relatively common for physicists. When Physics World asked – via an unscientific poll on the magazine’s Facebook page – what steps physicists had taken to pursue their careers, 38% of the 111 respondents said they had moved more than 500 miles at least once, while an additional 13% had moved a shorter distance. A separate poll on the most important factor for choosing a postdoctoral position found that “location” got the lowest score of all the options offered, attracting a measly three votes out of 63.

The problem is that after a while, moving around becomes more problematic. “Being on two or three-year contracts throughout our late 20s and early 30s means it’s really hard to plan a long-term future – buying a house, having children and so on,” says Sarah Kendrew, an astrophysicist who moved from London to the University of Leiden in the Netherlands before obtaining her current post at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. “I really find that I’ve had to be flexible and readjust my goals and expectations according to where work takes me.”

Moving around can be particularly trying for early-career researchers with spouses, children or other relatives who depend on them. After obtaining his PhD from the University of Manchester in the UK, Alan Duffy – who was, at the time, single – moved to Perth, Australia, to do postdoctoral research at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy. That decision was easy, he says, but now that he has a partner, his subsequent 3000 km move to the University of Melbourne required some hard thinking. “It was too good an offer to refuse, but only because my partner was able to make it work for her career,” he says. “Some postdocs just won’t be this lucky.”

In addition to the infamous “two-body problem”, in which academic couples struggle to find two research jobs in the same location, there is also a less well-known dilemma affecting physicists who are gay. Legislation on civil partnerships and social attitudes towards homosexuality varies widely among different countries and US states, observes Elena Long, a PhD student at Kent State University in Ohio who has worked on raising awareness of gay, lesbian and transgender issues in physics. Because of this variation, she says, gay physicists may have to balance an attractive job offer with concerns about being accepted in the local community.

In some cases, the need for mobility can prompt or hasten a decision to leave academic research. “One reason why academia doesn’t appeal to me so much is the lack of real freedom to choose where you want to live,” says Barnaby Rowe, an astrophysics postdoc at University College London who plans to leave research to train as a secondary-school teacher. “There are a number of places where you can do astronomy, but they’re quite thinly spread. If a job comes up, you may not get another job offer, so you take it…That lack of flexibility is tough on family members, and research is not something that I love enough to wish to inflict that on them anymore.”

- For more information on mobility in physics careers, listen to our podcast “Going where the beam is good”

Further information

www.vitae.ac.uk

http://scienceisvital.org.uk

www.nsf.gov/statistics