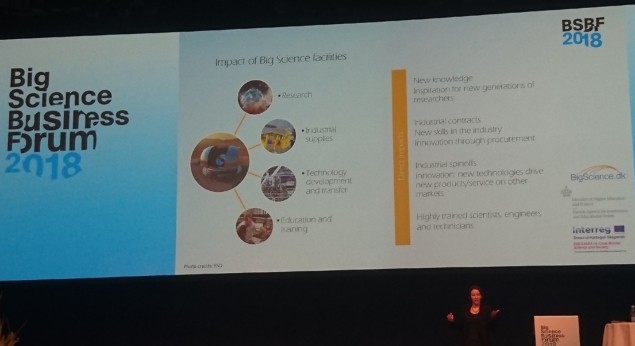

Speakers at the Big Science Business Forum in Copenhagen, Denmark explore the ways that companies and scientific facilities can work together

What do a particle accelerator, a space agency, a free-electron laser lab and an experimental fusion reactor have in common?

The answer – or, at least, the most relevant answer for the inaugural Big Science Business Forum (BSBF) here in Copenhagen, Denmark – is the network of companies that supply them with equipment and services. Although the scientific goals of CERN, ESA, the European XFEL and the ITER fusion project are very different, when you get down to the nuts and bolts of everyday operations, the technologies required to probe the fundamental nature of the universe and to explore our little corner of it are strikingly similar. And if your company can make instruments that can withstand the harsh environment of space, then maybe you ought to consider building some that can operate in a fusion reactor, too.

That was one of the messages at the BSBF plenary session on “Big Science as a Market”, which featured speakers from several companies where big science is also big business. Among them was Gaizka Murga-Llano, astronomy business manager at the Bilbao-based engineering and construction firm IDOM. Their involvement in the big-science market dates back to 2005, when IDOM took part in a design contest for the dome of the Extremely Large Telescope. At the time, the instrument known as the E-ELT (it’s now just the ELT, in a rare example of an inverse relationship between acronym complexity and time) was intended to be 100 m in diameter, and a traditional dome was not considered feasible. Over the subsequent decade, however, both budget and technical constraints forced managers at the European Southern Observatory (ESO) to scale back their plans. Throughout that period, Murga-Llano explained that IDOM worked with the ESO to develop designs that met the instrument’s evolving needs; today, construction on a 39 m ELT is under way at the ESO site in Cerro Armazones, Chile, with first light expected in 2024.

The story of IDOM and the ELT nicely illustrates some of the challenges that companies – especially small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) – face in working with big-science facilities. “If you are in the development phase, and every three months, you have to tell your bosses or your shareholders that the interesting commercial returns will come in five years, it is not very easy,” said Kurt Ebbinghaus, who is now an industry liaison officer at Fusion 4 Energy (the umbrella organization for ITER) but was previously managing director at the industrial-services firm Bilfinger Noell. Another of the session’s speakers, Jens William Larsen, made a similar point, explaining that when his small coatings firm, Polyteknik AS, works with industrial customers, they measure timelines in hours, days and weeks. With their big-science customers, however, they have to talk about months, years and decades.

In some cases, there are cultural barriers, too. Big-science facilities are interested in scientific discoveries and grand challenges, Larsen observed, but “we are just practical guys who want to run a business, who want to make some products. How do we combine those perspectives?” Although the rewards of interacting are significant for both sides – contracts for the companies; expertise and a more robust supplier base for the scientific organization – the overwhelming message from the speakers is that these interactions don’t happen on their own.

“We are just practical guys who want to run a business, who want to make some products. How do we combine those perspectives?”

Jens William Larsen, Polyteknik AS

Toward the end of the session, one of the BSBF co-organizers, Juliette Forneris, offered some concrete suggestions for improving the state of the big-science market. Forneris is the Industrial Liaison Officer (ILO) for both CERN and the ESO in Denmark, where the national government set up an umbrella group several years ago to help Danish firms engage with all of the Big Science organizations mentioned above, plus the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) and the European Spallation Source under construction across the Øresund in Sweden. In her view, one of the biggest barriers, especially for small firms, is the maze of different procurement procedures in operation at the different scientific facilities. In many cases, these procedures are written into the facility’s founding documents, so changing them would be next to impossible. However, Forneris believes that facilities could do a better job of communicating their rules to companies – especially those that haven’t worked with big science organizations before, and need an entry point.

That last part is important, because as IDOM’s example shows, one big-science project often leads to another. Barely a decade after they submitted their first ELT design to the ESO, the firm now has a client portfolio that reads like a who’s who of major scientific facilities. “Our previous work on the astronomy field, and especially the ELT, made it easier to work on the ITER programme,” said Murga-Llano. “If you are thinking of doing something, my advice is, go for it. It’s fascinating.”