By Margaret Harris

Last Sunday I went up to Cheltenham for the final day of the town’s annual Science Festival. My plan was to meet the University of Maryland theorist Jim Gates before lunch and then stay to hear his lecture on science and policy.

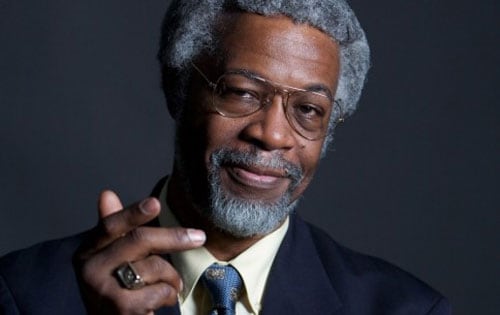

I was already somewhat familiar with Gates’ research thanks to a feature he wrote for Physics World in June 2010. I could also have made an educated guess about his activities as a member of the President’s Council of Advisers on Science and Technology (PCAST). However, I knew very little about his personal history before his evening lecture, when he was interviewed by the physicist and science presenter Jim Al-Khalili.

Gates was born in 1950 and grew up during a period when African-Americans faced severe institutionalized discrimination across the US. However, being from a military family helped insulate him from some of the worst effects, and he told the audience that he didn’t feel the full impact until his family moved to Florida after he turned 11. For the first time, he attended a racially segregated school, and there, he said, he had “the very curious experience of having to learn how to be black”.

This experience was partly positive, Gates joked, since it meant he had to stop liking the Beach Boys and start liking the Temptations (“That’s an improvement,” Al-Khalili replied, to ripples of laughter from the audience). Soon, however, Gates said he “came to understand how segregation diminishes people who are subjected to it”. When one of his (black) classmates told him “You’re smart, but you’ll never be as smart as a white boy”, Gates said at first he was shocked. But by the time he was a senior in high school, he’d come to believe that, while he excelled in science and mathematics, he should not bother applying to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) because, as he told his father, “you know they do not let people like us go to places like that.”

Fortunately, Jim Gates Senior was having none of it. According to his son, the elder Gates never attended college, but he had taught himself advanced mathematics from textbooks and his long Army career included service in northern France during the Second World War. He was not, in short, the kind of person you said “no” to, and he forced his son to apply to MIT anyway. About a month later, Gates said, “I came home to find Dad sitting on the porch, smiling the biggest smile ever…I knew I’d been accepted [and] we had one of those awkward, ‘man-hug’ things.”

For Gates, getting into MIT was just the start. He followed his Bachelor’s degrees with a PhD at MIT and postdocs at Harvard and Caltech, and has gone on to win numerous honours, including a National Medal of Science and membership of PCAST. But to achieve all that, I realized, he must have managed to shake off the diminishing attitudes he’d absorbed as a child in the segregated South. So at the end of his talk, I asked him how he’d done it.

Gates replied that it didn’t happen right away. When he arrived at MIT, he thought he would be “the dumbest kid in every class”. But when he found out that he wasn’t, it gave him a confidence boost. Then, during a summer job at an electronics firm, a senior engineer told him to stop solving problems so quickly because it was making everyone else look bad. Gates responded by spending some of his working hours studying his textbook on differential equations. By the end of the summer, he’d managed to solve the Coloumb wave equation on his own. His confidence soared, and from there, he, said, he never really looked back – not even when he struggled to understand integral calculus.

Jim Gates’ cure for self-doubt won’t work for everyone. Even for him, I doubt it was easy. It is, however, easy to understand. It’s called success.