The cost of war is most often framed in terms of the loss of human life and economic devastation. But, as Benjamin Skuse discovers, the world’s militaries also account for over 5% of global greenhouse-gas emissions, with war causing untold and sometimes irreparable damage to the environment

Despite not being close to the frontline of Russia’s military assault on Ukraine, life at the Ivano-Frankivsk National Technical University of Oil and Gas is far from peaceful. “While we continue teaching and research, we operate under constant uncertainty – air raid alerts, electricity outages – and the emotional toll on staff and students,” says Lidiia Davybida, an associate professor of geodesy and land management.

Last year, the university became a target of a Russian missile strike, causing extensive damage to buildings that still has not been fully repaired – although, fortunately, no casualties were reported. The university also continues to leak staff and students to the war effort – some of whom will tragically never return – while new student numbers dwindle as many school graduates leave Ukraine to study abroad.

Despite these major challenges, Davybida and her colleagues remain resolute. “We adapt – moving lectures online when needed, adjusting schedules, and finding ways to keep research going despite limited opportunities and reduced funding,” she says.

Resolute research

Davybida’s research focuses on environmental monitoring using geographic information systems (GIS), geospatial analysis and remote sensing. She has been using these techniques to monitor the devastating impact that the war is having on the environment and its significant contribution to climate change.

In 2023 she published results from using Sentinel-5P satellite data and Google Earth Engine to monitor the air quality impacts of war on Ukraine (IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 1254 012112). As with the COVID-19 lockdowns worldwide, her results reveal that levels of common pollutants such as carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide were, on average, down from pre-invasion levels. This reflects the temporary disruption to economic activity that war has brought on the country.

More worrying, from an environment and climate perspective, were the huge concentrations of aerosols, smoke and dust in the atmosphere. “High ozone concentrations damage sensitive vegetation and crops,” Davybida explains. “Aerosols generated by explosions and fires may carry harmful substances such as heavy metals and toxic chemicals, further increasing environmental contamination.” She adds that these pollutants can alter sunlight absorption and scattering, potentially disrupting local climate and weather patterns, and contributing to long-term ecological imbalances.

A significant toll has been wrought by individual military events too. A prime example is Russia’s destruction of the Kakhovka Dam in southern Ukraine in June 2023. An international team – including Ukrainian researchers – recently attempted to quantify this damage by combining on-the-ground field surveys, remote-sensing data and hydrodynamic modelling; a tool they used for predicting water flow and pollutant dispersion.

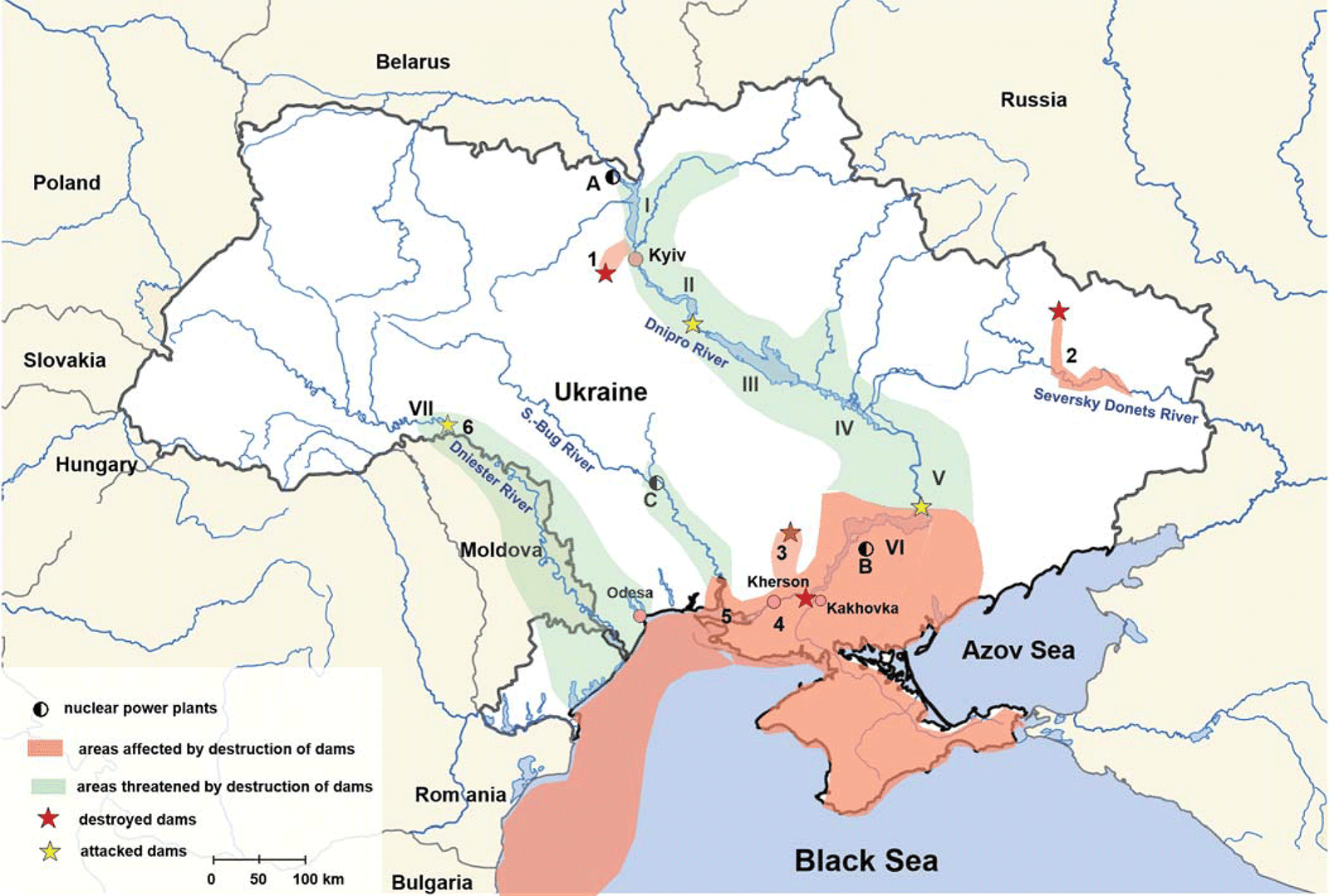

The results of this work are sobering (Science 387 1181). Though 80% of the ecosystem is expected to re-establish itself within five years, the dam’s destruction released as much as 1.7 cubic kilometres of sediment contaminated by a host of persistent pollutants, including nitrogen, phosphorous and 83,000 tonnes of heavy metals. Discharging this toxic sludge across the land and waterways will have unknown long-term environmental consequences for the region, as the contaminants could be spread by future floods, the researchers concluded (figure 1).

1 Dam destruction

This map shows areas of Ukraine affected or threatened by dam destruction in military operations. Arabic numbers 1 to 6 indicate rivers: Irpen, Oskil, Inhulets, Dnipro, Dnipro-Bug Estuary and Dniester, respectively. Roman numbers I to VII indicate large reservoir facilities: Kyiv, Kaniv, Kremenchuk, Kaminske, Dnipro, Kakhovka and Dniester, respectively. Letters A to C indicate nuclear power plants: Chornobyl, Zaporizhzhia and South Ukraine, respectively.

Dangerous data

A large part of the reason for the researchers’ uncertainty, and indeed more general uncertainty in environmental and climate impacts of war, stems from data scarcity. It is near-impossible for scientists to enter an active warzone to collect samples and conduct surveys and experiments. Environmental monitoring stations also get damaged and destroyed during conflict, explains Davybida – a wrong she is attempting to right in her current work. Many efforts to monitor, measure and hopefully mitigate the environmental and climate impact of the war in Ukraine are therefore less direct.

In 2022, for example, climate-policy researcher Mathijs Harmsen from the PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency and international collaborators decided to study the global energy crisis (which was sparked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine) to look at how the war will alter climate policy (Environ. Res. Lett. 19 124088).

They did this by plugging in the most recent energy price, trade and policy data (up to May 2023) into an integrated assessment model that simulates the environmental consequences of human activities worldwide. They then imposed different potential scenarios and outcomes and let it run to 2030 and 2050. Surprisingly, all scenarios led to a global reduction of 1–5% of carbon dioxide emissions by 2030, largely due to trade barriers increasing fossil fuel prices, which in turn would lead to increased uptake of renewables.

But even though the sophisticated model represents the global energy system in detail, some factors are hard to incorporate and some actions can transform the picture completely, argues Harmsen. “Despite our results, I think the net effect of this whole war is a negative one, because it doesn’t really build trust or add to any global collaboration, which is what we need to move to a more renewable world,” he says. “Also, the recent intensification of Ukraine’s ‘kinetic sanctions’ [attacks on refineries and other fossil fuel infrastructure] will likely have a larger effect than anything we explored in our paper.”

Elsewhere, Toru Kobayakawa was, until recently, working for the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), leading the Ukraine support team. Kobayakawa used a non-standard method to more realistically estimate the carbon footprint of reconstructing Ukraine when the war ends (Environ. Res.: Infrastruct. Sustain. 5 015015). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and other international bodies only account for carbon emissions within the territorial country. “The consumption-based model I use accounts for the concealed carbon dioxide from the production of construction materials like concrete and steel imported from outside of the country,” he says.

Using an open-source database Eora26 that tracks financial flows between countries’ major economic sectors in simple input–output tables, Kobayakawa calculated that Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction will amount to 741 million tonnes carbon dioxide equivalent over 10 years. This is 4.1 times Ukraine’s pre-war annual carbon-dioxide emissions, or the combined annual emissions of Germany and Austria.

However, as with most war-related findings, these figures come with a caveat. “Our input–output model doesn’t take into account the current situation,” notes Kobayakawa “It is the worst-case scenario.” Nevertheless, the research has provided useful insights, such as that the Ukrainian construction industry will account for 77% of total emissions.

“Their construction industry is notorious for inefficiency, needing frequent rework, which incurs additional costs, as well as additional carbon-dioxide emissions,” he says. “So, if they can improve efficiency by modernizing construction processes and implementing large-scale recycling of construction materials, that will contribute to reducing emissions during the reconstruction phase and ensure that they build back better.”

Military emissions gap

As the experiences of Davybida, Harmsen and Kobayakawa show, cobbling together relevant and reliable data in the midst of war is a significant challenge, from which only limited conclusions can be drawn. Researchers and policymakers need a fuller view of the environmental and climate cost of war if they are to improve matters once a conflict ends.

That’s certainly the view of Benjamin Neimark, who studies geopolitical ecology at Queen Mary University of London. He has been trying for some time to tackle the fact that the biggest data gap preventing accurate estimates of the climate and environmental cost of war is military emissions. During the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), for example, he and colleagues partnered with the Conflict and Environment Observatory (CEOBS) to launch The Military Emissions Gap, a website to track and trace what a country accounts for as its military emissions to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

At present, reporting military emissions is voluntary, so data are often absent or incomplete – but gathering such data is vital. According to a 2022 estimate extrapolated from the small number of nations that do share their data, the total military carbon footprint is approximately 5.5% of global emissions. This would make the world’s militaries the fourth biggest carbon emitter if they were a nation.

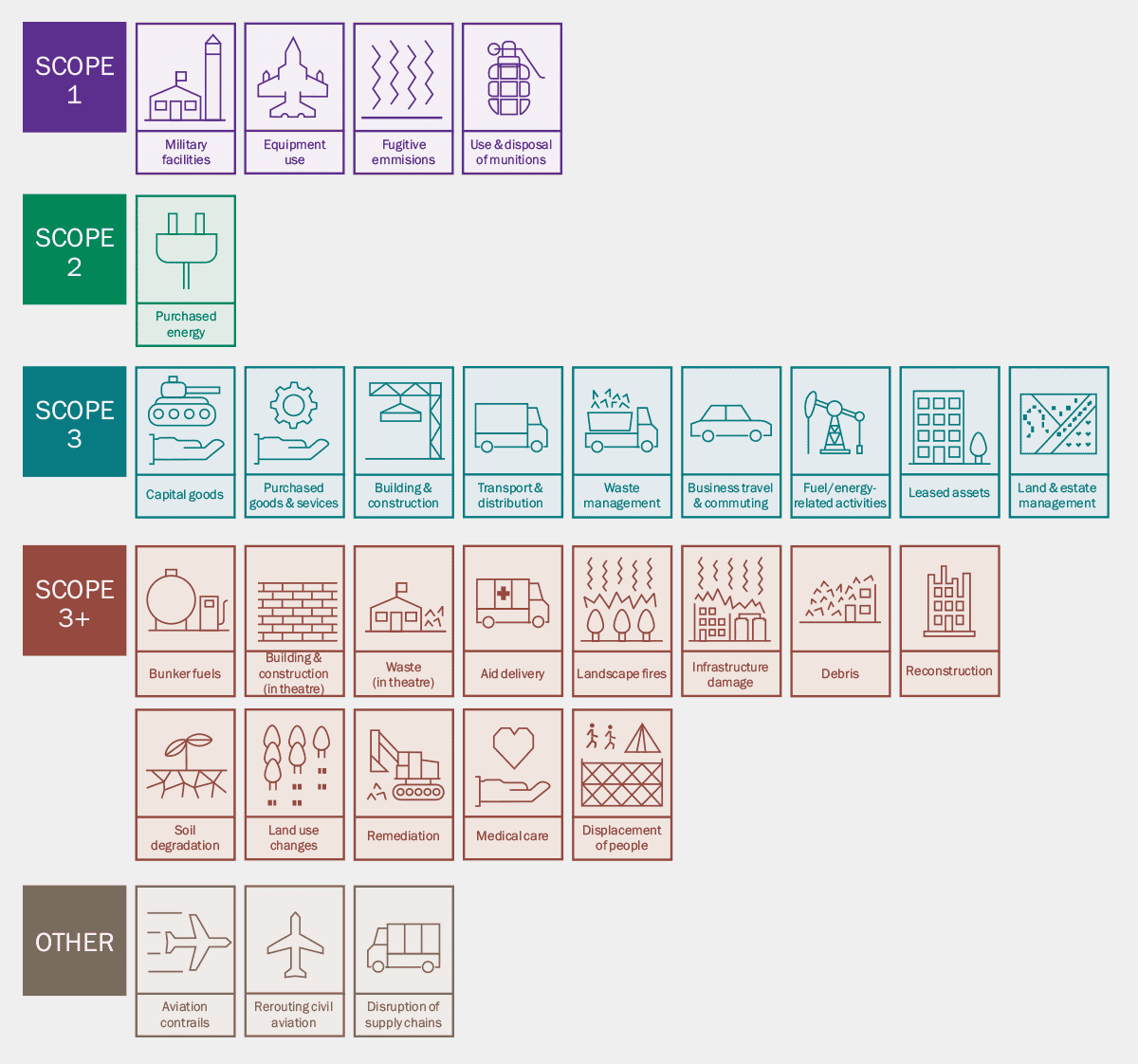

The website is an attempt to fill this gap. “We hope that the UNFCCC picks up on this and mandates transparent and visible reporting of military emissions,” Neimark says (figure 2).

2 Closing the data gap

Current United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) greenhouse-gas emissions reporting obligations do not include all the possible types of conflict emissions, and there is no commonly agreed methodology or scope on how different countries collect emissions data. In a recent publication War on the Climate: a Multitemporal Study of Greenhouse Gas Emissions of the Israel-Gaza Conflict, Benjamin Neimark et al. came up with this framework, using the UNFCCC’s existing protocols. These reporting categories cover militaries and armed conflicts, and hope to highlight previously “hidden” emissions.

Measuring the destruction

Beyond plugging the military emissions gap, Neimark is also involved in developing and testing methods that he and other researchers can use to estimate the overall climate impact of war. Building on foundational work from his collaborator, Dutch climate specialist Lennard de Klerk – who developed a methodology for identifying, classifying and providing ways of estimating the various sources of emissions associated with the Russia–Ukraine war – Neimark and colleagues are trying to estimate the greenhouse-gas emissions from the Israel–Gaza conflict.

Their studies encompass pre-conflict preparation, the conflict itself and post-conflict reconstruction. “We were working with colleagues who were doing similar work in Ukraine, but every war is different,” says Neimark. “In Ukraine, they don’t have large tunnel networks, or they didn’t, and they don’t have this intensive, incessant onslaught of air strikes from carbon-intensive F16 fighter aircraft.” Some of these factors, like the carbon impact of Hamas’ underground maze of tunnels under Gaza, seem unquantifiable, but Neimark has found a way.

“There’s some pretty good data for how big these are in terms of height, the amount of concrete, how far down they’re dug and how thick they are,” says Neimark. “It’s just the length we had to work out based on reported documentation.” Finding the total amount of concrete and steel used in these tunnels involved triangulating open-source information with media reports to finalize an estimate of the dimensions of these structures. Standard emission factors could then be applied to obtain the total carbon emissions. According to data from Neimark’s Confronting Military Greenhouse Gas Emissions report, the carbon emissions from construction of concrete infrastructure by both Israel and Hamas were more than the annual emissions of 33 individual countries and territories (figure 3).

3 Climate change and the Gaza war

Data from Benjamin Neimark, Patrick Bigger, Frederick Otu-Larbi and Reuben Larbi’s Confronting Military Greenhouse Gas Emissions report estimates the carbon emissions of the war in Gaza for three distinct periods: direct war activities; large-scale war infrastructure; and future reconstruction.

The impact of Hamas’ tunnels and Israel’s “iron wall” border fence are just two of many pre-war activities that must be factored in to estimate the Israel–Gaza conflict’s climate impact. Then, the huge carbon cost of the conflict itself must be calculated, including, for example, bombing raids, reconnaissance flights, tanks and other vehicles, cargo flights and munitions production.

Gaza’s eventual reconstruction must also be included, which makes up a big proportion of the total impact of the war, as Kobayakawa’s Ukraine reconstruction calculations showed. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has been systematically studying and reporting on “Sustainable debris management in Gaza” as it tracks debris from damaged buildings and infrastructure in Gaza since the outbreak of the conflict in October 2023. Alongside estimating the amounts of debris, UNEP also models different management scenarios – ranging from disposal to recycling – to evaluate the time, resource needs and environmental impacts of each option.

Visa restrictions and the security situation have prevented UNEP staff from entering the Gaza strip to undertake environmental field assessments to date. “While remote sensing can provide a valuable overview of the situation … findings should be verified on the ground for greater accuracy, particularly for designing and implementing remedial interventions,” says a UNEP spokesperson. They add that when it comes to the issue of contamination, UNEP needs “confirmation through field sampling and laboratory analysis” and that UNEP “intends to undertake such field assessments once conditions allow”.

The main risk from hazardous debris – which is likely to make up about 10–20% of the total debris – arises when it is mixed with and contaminates the rest of the debris stock. “This underlines the importance of preventing such mixing and ensuring debris is systematically sorted at source,” adds the UNEP spokesperson.

The ultimate cost

With all these estimates, and adopting a Monte Carlo analysis to account for uncertainties, Neimark and colleagues concluded that, from the first 15 months of the Israel–Gaza conflict, total carbon emissions were 32 million tonnes, which is huge given that the territory has a total area of just 365 km². The number also continues to rise.

Why does this number matter? When lives are being lost in Gaza, Ukraine, and across Sudan, Myanmar and other regions of the world, calculating the environmental and climate cost of war might seem like something only worth bothering about when the fighting stops.

But doing so even while conflicts are taking place can help protect important infrastructure and land, avoid environmentally disastrous events, and to ensure the long rebuild, wherever the conflict may be happening, is informed by science. The UNEP spokesperson says that it is important to “systematically integrate environmental considerations into humanitarian and early recovery planning from the outset” rather than treating the environment as an afterthought. They highlight that governments should “embed it within response plans – particularly in areas where it can directly impact life-saving activities, such as debris clearance and management”.

With Ukraine still in the midst of war, it seems right to leave the final word to Davybida. “Armed conflicts cause profound and often overlooked environmental damage that persists long after the fighting stops,” she says. “Recognizing and monitoring these impacts is vital to guide practical recovery efforts, protect public health, prevent irreversible harm to ecosystems and ensure a sustainable future.”

- The journal Environmental Research Letters has launched a Focus on Initial and Enduring Environmental Consequences of Armed Conflict, which is accepting authors’ expressions of interest until 28 February 2026.