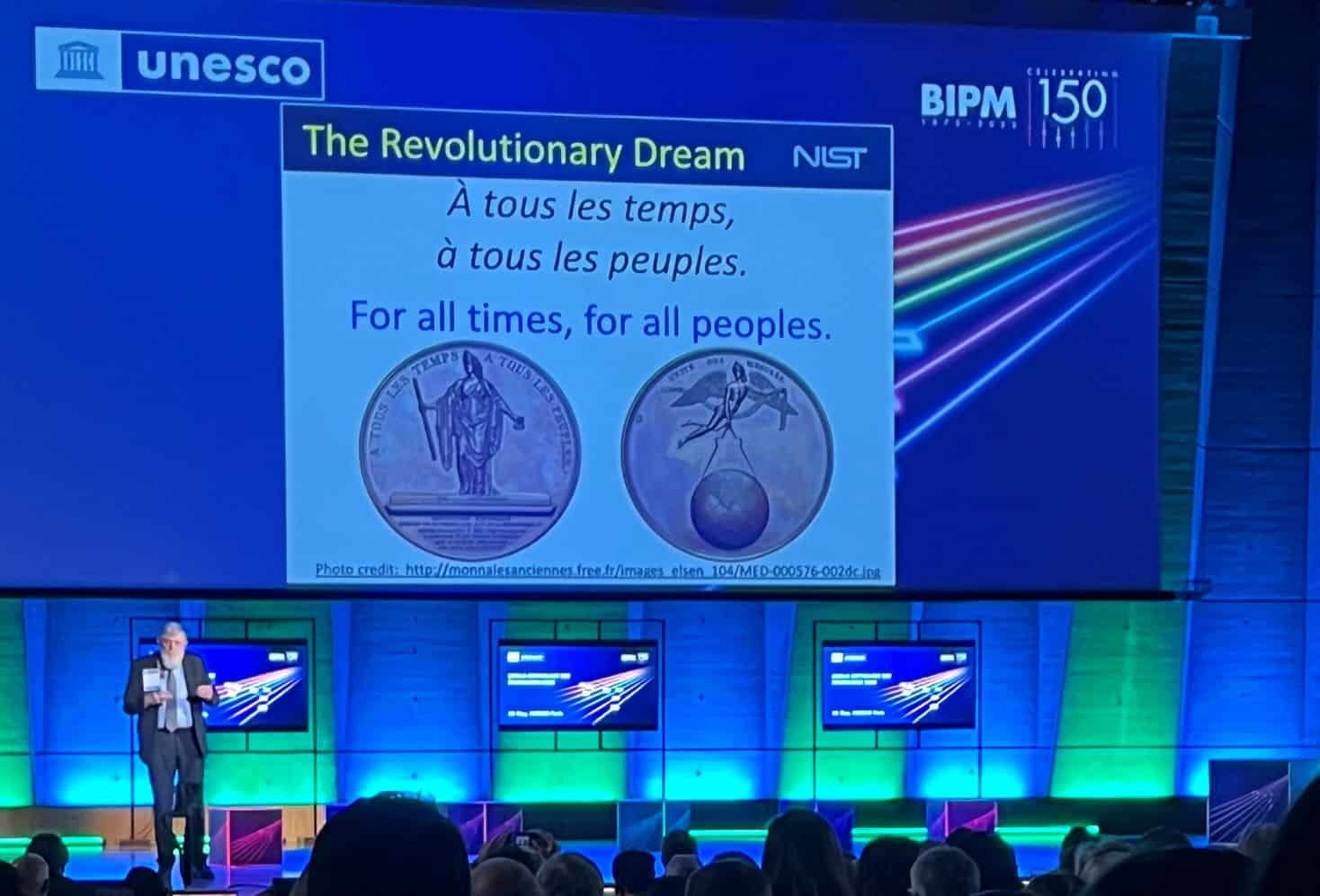

The 20th of May is World Metrology Day, and this year it was extra special because it was also the 150th anniversary of the treaty that established the metric system as the preferred international measurement standard. Known as the Metre Convention, the treaty was signed in 1875 in Paris, France by representatives of all 17 nations that belonged to the Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (BIPM) at the time, making it one of the first truly international agreements. Though nations might come and go, the hope was that this treaty would endure “for all times and all peoples”.

To celebrate the treaty’s first century and a half, the BIPM and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) held a joint symposium at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris. The event focused on the achievements of BIPM as well as the international scientific collaborations the Metre Convention enabled. It included talks from the Nobel prize-winning physicist William Phillips of the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the BIPM director Martin Milton, as well as panel discussions on the future of metrology featuring representatives of other national metrology institutes (NMIs) and metrology professionals from around the globe.

A long and revolutionary tradition

The history of metrology dates back to ancient times. As UNESCO’s Hu Shaofeng noted in his opening remarks, the Egyptians recognized the importance of precision measurements as long ago as the 21st century BCE. Like other early schemes, the Egyptians’ system of measurement used parts of the human body as references, with units such as the fathom (the length of a pair of outstretched arms) and the foot. This was far from ideal since, as Phillips pointed out in his keynote address, people come in various shapes and sizes. These variations led to a profusion of units. By some estimates, pre-revolutionary France had a whopping 250,000 different measures, with differences arising not only between towns but also between professions.

The French Revolutionaries were determined to put an end to this mess. In 1795, just six years after the Revolution, the law of 18 Geminal An III (according to the new calendar of the French Republic) created a preliminary version of the world’s first metric system. The new system tied length and mass to natural standards (the metre was originally one-forty-millionth of the Paris meridian, while the kilogram is the mass of a cubic decimetre of water), and it became the standard for all of France in 1799. That same year, the system also became more practical, with units becoming linked, for the first time, to physical artefacts: a platinum metre and kilogram deposited in the French National Archives.

When the Metre Convention adopted this standard internationally 80 years later, it kick-started the construction of new length and mass standards. The new International Prototype of the Metre and International Prototype of the Kilogram were manufactured in 1879 and officially adopted as replacements for the Revolutionaries’ metre and kilogram in 1889, though they continued to be calibrated against the old prototypes held in the National Archives.

A short history of the BIPM

The BIPM itself was originally conceived as a means of reconciling France and Germany after the 1870–1871 Franco–Prussian War. At first, its primary roles were to care for the kilogram and metre prototypes and to calibrate the standards of its member states. In the opening decades of the 20th century, however, it extended its activities to cover other kinds of measurements, including those related to electricity, light and radiation. Then, from the 1960s onwards, it became increasingly interested in improving the definition of length, thanks to new interferometer technology that made it possible to measure distance at a precision rivalling that of the physical metre prototype.

It was around this time that the BIPM decided to replace its expanded metric system with a framework encompassing the entire field of metrology. This new framework consisted of six basic units – the metre, kilogram, second, ampere, degree Kelvin (later simply the kelvin), candela and mole – plus a set of “derived” units (the Newton, Hertz, Joule and Watt) built from the six basic ones. Thus was born the International System of Units, or SI after the French initials for Système International d’unités.

The next major step – a “brilliant choice”, in Phillips’ words – came in 1983, when the BIPM decided to redefine the metre in terms of the speed of light. In the future, the Bureau decreed that the metre would officially be the length travelled by light in vacuum during a time interval of 1/299,792,458 seconds.

This decision set the stage for defining the rest of the seven base units in terms of natural fundamental constants. The most recent unit to join the club was the kilogram, which was defined in terms of the Planck constant, h, in 2019. In fact, the only base unit currently not defined in terms of a fundamental constant is the second, which is instead determined by the transition between the two hyperfine levels of the ground state of caesium-133. The international metrology community is, however, working to remedy this, with meetings being held on the subject in Versailles this month.

Measurement affects every aspect of our daily lives, and as the speakers at last week’s celebrations repeatedly reminded the audience, a unified system of measurement has long acted as a means of building trust across international and disciplinary borders. The Metre Convention’s survival for 150 years is proof that peaceful collaboration can triumph, and it has allowed humankind to advance in ways that would not have been possible without such unity. A lesson indeed for today’s troubled world.