Geek Nation: How Indian Science is Taking Over the World

Angela Saini

2011 Hodder & Stoughton £20.00/$26.75hb 280pp

“India was once one of the most powerful scientific nations of all,” writes Angela Saini in the preface to Geek Nation. She bases her claim on the fact that Indians were using algebra, the zero and square roots centuries before the West, and that Indian astronomers are believed to have been the first to realize that day and night are caused by the Earth’s rotation. Then Indian science went into a slump, Europe had its Enlightenment and modern science ended up being shaped mostly in the West. But now, Saini writes, “this impoverished tea- and cotton-growing backwater is starting to reclaim the scientific legacy that it lost thousands of years ago”, and she is “here to learn about this rediscovered nation of geeks”.

Unfortunately, this highlights one of the problems with Geek Nation, which is that Saini, a UK-based science journalist, seems to know from the outset what she wants to find in India. In her first interview on arriving in the country, she tells one of the pioneers of India’s space programme that her book is to be titled Geek Nation and explains that, to her, “geekiness is all about passion. It’s about choosing science and technology or another intellectual pursuit…and devoting your life to it.”

The first few people she meets do not live up to her expectations. One of them is a physics prodigy who turns out not to be curious or brilliant but just hard-working and dreary. She spends a week in one of the most selective engineering colleges in India, the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi (IITD), but finds the place dilapidated and the students uncreative and unresponsive. She visits India’s largest software company, Tata Consultancy Services, and finds no trace of innovation. Saini is disappointed at not finding any geeks: “All I can see are drones.”

Then, just when Saini wonders if “India is genuinely turning into a geeky, scientific society, or whether it’s just hype”, she visits IBM’s India research lab and sees the development of the Spoken Web, a voice-based version of the Internet that can be accessed through a phone call by the underprivileged or illiterate. She visits a start-up in Bangalore where she finds innovation. And she goes back to IITD and finds that things there are not as bad as she initially thought. She even finds a student who is interested in design and is writing a novel about robots, and enthusiastically hails him as “a real geek”.

Despite her (belated) success in finding someone who conforms to it, this narrative created around “geekiness” feels forced. Even Saini’s constant use of the word “geek” – perhaps to justify the book’s title – becomes tiresome. Hers is a “geeky mission”; the founder of India’s space programme, Vikram Sarabhai, was a “good-looking geek”; and a tuberculosis researcher whose work may have damaged her health is saluted as a “true geek”.

A bigger problem, though, is Saini’s grasp of the facts. In her introductory chapter, for example, she writes that the first Indian prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, “even wedged a plea into the Indian constitution, announcing, ‘It shall be the duty of every citizen of India to develop the scientific temper’.” She repeats this claim in a later chapter, but although this line does appear in the Indian constitution, it was introduced more than a decade after Nehru’s death. Elsewhere, an environmental activist tells Saini that “quantum theory teaches you that things are connected”. Saini guesses that the activist is mixing up unrelated branches of science by invoking the idea of quantum entanglement, “which says that every particle in the universe is connected to every other, however distant it is, on a fundamental level” – yet this quasi-mystical definition is scarcely better than the activist’s claim. Then there is a stray factoid that turns out to be only three-quarters true: “[Tuberculosis] killed Chekhov, Kafka, Keats and Napoleon.”

In other places, Saini comes across as fanciful in her perceptions, writing of one interviewee that he “spends so much time designing computer programs that he speaks in peculiarly clipped sentences”. When she meets a professor who has chosen science over religion, and comes across as calm and well adjusted, Saini even appears to indulge in a bit of “hot reading” when she says that behind his “happy, baggy eyes, I can see how hard the tension between the two must have been for him”.

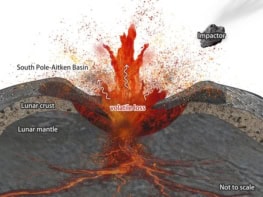

There are too many instances of error and imprecision in Geek Nation to list, but a particularly flagrant episode is Saini’s description of India’s first Moon mission. According to Saini, the probe Chandrayaan-1 was launched from “a remote island” and it “wandered the lunar surface for months” before being “forced to come back to Earth”. But the launch site, Sriharikota, is just off the Indian coast and is easily accessible by road. Chandrayaan-1 was an orbiter with an impact probe, had no rover capable of wandering and only its radio signals ever came back to Earth. These errors end up compromising the wider argument they are part of. In addition to factual errors, the book contains unattributed perceptions about the Chandrayaan-1 mission, such as this (p5): “Nobody was sure whether the project would be a success or a waste of time, but the reputation of Indian science depended on it. Many in the scientific community had always assumed that India would never be able to afford a space mission.” Statements such as these call upon the reader to trust Saini’s command of relevant facts and judgement, but this becomes increasingly difficult as the book progresses.

Despite its limitations, Geek Nation does manage to provide a broadly impressionistic view of Indian science today. The book’s sub-title, “How Indian Science is Taking Over the World”, is debatable, but there is no doubt that steady progress is being made. Saini has chosen material that is rich in its potential to yield insights about science and technology in India and the cultural battles being fought around it: the education system; genetically modified crops; the sometimes overlapping boundaries between science, superstition and religion; the possibilities created by electronic governance in a country reeling from corruption; open-source drug discovery; and nuclear power. She also meets an array of people – industrialists, scientists, students, academics and traditional scholars – whose ideas are often interesting or insightful. With some better fact-checking and with a less predetermined view, Geek Nation might have been a very good book.