Will a world that’s 1.5 °C warmer experience more hurricanes and typhoons? How much will mountain glaciers retreat? Which regions will suffer more frequent drought and crop failure? Not only are there questions about what this level of temperature rise will look like but also what we’d have to do to limit warming to this amount, and whether it’s worth pulling out all the stops to do so.

In October 2018 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) releases its Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C (SR15). The need for this report arose from the Paris Agreement of December 2015, when the 195 members of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) agreed to try to limit the temperature increase to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and, crucially, to aim for a 1.5 °C rise at most. Before the Paris meeting, much of the focus had been on examining how much warming might occur by a particular time; 2050, 2080 or 2100, say. “The Paris Agreement made the scientific community reframe the questions they ask, to examine what could the world be like when it reaches a particular temperature,” says Kristie Ebi from the University of Washington, US, who’s a lead author on the 1.5 °C report.

There’s been extensive research investigating the impact of 2 °C of warming, but 1.5 °C hadn’t been looked at in detail. “The 1.5 °C global warming target caught many scientists off guard,” says Dann Mitchell, a climate scientist at the University of Bristol, UK, who also contributed to the 1.5 °C report. “We had performed lots of analysis for climate impacts at higher temperature limits, but not this limit.”

We needed to ask ‘are impacts in societally relevant sectors detectable between the two temperature limits?’ And given the answer to that, are the costs of limiting global warming to 1.5 °C justified?

Dann Mitchell

Over the last two years, scientists have worked frantically to estimate the impacts of 1.5 °C of warming and publish their findings in peer-reviewed journals. The SR15 authors have had to assess this body of research and compose an accurate, comprehensive and objective report. Three major questions loomed large. “Given the political willpower needed, and the considerable cost of stabilizing climate at the lower limit, the report needed to ask whether 1.5 °C was even possible given how much carbon we have already emitted into the atmosphere?” explains Mitchell. “Also we needed to ask ‘are impacts in societally-relevant sectors detectable between the two temperature limits?’ And given the answer to that, are the costs of limiting global warming to 1.5 °C justified?”

Fine-scale findings

Here it is the detail that is important: whether floods in Bangladesh will be significantly worse with 2 °C warming than 1.5 °C; whether wildfire risk in California will be amplified by the extra half degree of temperature rise; and whether tropical storms will cause noticeably more damage at the 2 °C threshold than at 1.5 °C.

One such question was how much European summers are likely to change. To answer it, Laura Suarez of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Germany, and her colleagues used a coupled climate model to simulate the evolution of the Earth’s climate under 1.5 °C and 2 °C conditions. “The ‘Grand Ensemble’ features a hundred potential Earths, and produces a hundred potential futures to robustly sample the influence of internal variability in the chaotic climate system,” says Suarez.

The Paris Agreement made the scientific community reframe the questions they ask

Kristie Ebi

The researchers found that, because of that large degree of internal variability, the difference between 1.5 °C and 2 °C of warming was not as great as you might expect, with only 10% of the warmest European summers avoided by keeping within the 1.5 °C limit. But that small difference could still be worth achieving. “These events would correspond to the most extreme and severe heat waves, the ones with the most critical consequences,” says Suarez. The team published their findings in Environmental Research Letters (ERL).

What’s more, Suarez and her colleagues showed that the differences between extreme summer temperatures are not evenly distributed across the continent. For moderately extreme events – the kind of heatwave experienced once in every 20 years –Southern Europe was the most vulnerable, but for once in a century heatwaves Central Europe was most at risk. “All in all, at 2 °C of warming, extreme events will become warmer in Southern and Eastern Europe; around 1.5 °C warmer than at 1.5 °C of global warming,” says Suarez. “Also, at 2 °C of warming there is an increased probability of very extreme events over countries like France, Germany and Poland, and these extremes could be up to 3 °C warmer than at 1.5 °C of warming.”

Sustainable development

As well as understanding what 1.5 °C of warming will feel like, the report explicitly assesses climate change mitigation and adaptation in the context of sustainable development. “My hope would be that this report can provide insights into how one can work towards achieving the full set of sustainability objectives that governments identified in 2015, including climate change protection,” says Joeri Rogelj of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria and Imperial College London, who co-ordinated one of the 1.5 °C report’s chapters. In particular, the report examines the complex interactions that occur when adaptation and mitigation measures are put in place, and the trade-offs associated with some decisions. “When we work out the cost of mitigation policies we also need to look at the co-benefits,” explains Ebi. “For example, the health benefits of a particular mitigation policy will often pay for the policy.”

1.5 °C warming limit needs ‘unprecedented changes in all aspects of society’

Preliminary findings certainly indicate that there are substantial economic benefits associated with meeting the 1.5 °C target. In a paper published in Nature in May 2018, Marshall Burke from Stanford University, US, and his colleagues, calculated that meeting the 1.5 °C target by the end of this century, instead of the more common 2 °C goal, would save the world $20 trillion.

Nonetheless, many scientists are sceptical that the 1.5 °C goal can be met. “I have to confess that I am doubtful that we can achieve this target, but I do believe that we may be in reach of 2 °C, albeit with a bit more luck and a huge amount more effort,” says Paul Valdes from the University of Bristol, UK. In particular, countries like China give Valdes optimism. “Although the pollution and emissions are high, China is clearly showing major commitments to change.”

But Valdes also cautions against being too fixated on the temperature targets themselves. “Sometimes I fear that these targets are seen as scientific absolutes,” he says. “For example, believing that if global temperatures exceed 2 °C, then we have ‘dangerous’ climate change, but that less than 2 °C will be okay; the reality is that there is no scientific definition of ‘dangerous’ climate change and, as far as we are aware, there is no sudden threshold. The impacts of climate change will become more and more serious as temperatures rise, but there is no sudden universal change at 1.5 or 2 °C.”

The most recent studies indicate that even if we do manage to keep a lid on rising temperatures, some key parts of the Earth system might be more sensitive to warming than previously thought. “Recent literature has consistently revised estimates to imply stronger and faster impacts with ice-sheet loss and sea-level rise,” says Rogelj.

However, relative to the “business as usual” scenario of 4 °C of warming, 2 °C will significantly reduce the high risks associated with climate change. The 2 °C limit has been chosen with care. As the recent UNFCCC Structured Expert Dialogue puts it, “2 °C of warming is better seen as an upper limit, a defence line that needs to be stringently defended, while less warming would be preferable”.

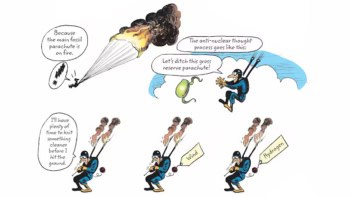

All these factors must be weighed up when deciding which path of action to take. Carbon removal or geoengineering might be ways forward, or maybe we need to accept that we will overshoot the 1.5 °C target but make plans to ramp the temperature back down as soon as possible. Once they’ve read the report, policymakers and governments have some hard thinking to do.