Courtesy: US Federal Government

By James Dacey

“Carbon in its light form will seek its way out of the ground or seabed. The present situation in the Gulf of Mexico is a poignant reminder of that fact.”

These are the words of Gary Schaffer, a geophysicist who works between three academic institutions in Chile and Denmark, referring to the idea of carbon sequestration.

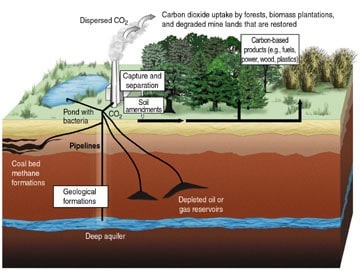

Large-scale sequestration projects would involve storing vast quantities of carbon dioxide beneath the ground as a way of reducing atmospheric levels of this greenhouse gas. Several types of site have been mentioned as potential carbon bunkers, including the deep ocean and depleted oil and gas reservoirs.

In fact, the idea is so popular that the European Union plans to invest billions of dollars within the next 10 years to develop large scale carbon capture and storage (CCS) facilities. The US is also keen with the Department of Energy funding 12 industrial CCS projects to conduct feasibility studies, four of which will be given the go-ahead to become operational by 2015.

But despite the political enthusiasm, it is not yet clear what the long term consequences of this solution would be and the potential impacts of gas leaking back into the atmosphere.

Schaffer has addressed this issue in a new paper published in Nature Geoscience.

By modelling a number of sequestration/leakage scenarios using a well known earth system model, Schaffer reaches several firm conclusions. These include the warning that CO2 stored in the deep ocean will return to the atmosphere within little time, so it will merely delay the inevitable warming effect. He also fears that this strategy would be unacceptably damaging to deep-sea wildlife.

Schaffer also looked at CO2 stored in reservoirs on land or beneath the ocean floor, finding that this may be more effective so long as CO2 leakage is restricted to 1% or less per thousand years.

He warns against thinking we can simply bury the gas again through “resequestration” because there are various engineering challenges in monitoring the rate of leakage. He is also worried about the burden resequestration would leave on future societies, comparing it to the long-term management of nuclear waste.

“The dangers of carbon sequestration are real and the development of this technique should not be used as an argument for continued high fossil fuel emissions,” says Schaffer.

“On the contrary, we should greatly limit CO2 emissions in our time to reduce the need for massive carbon sequestration and thus reduce unwanted consequences and burdens over many future generations from the leakage of sequestered CO2.”