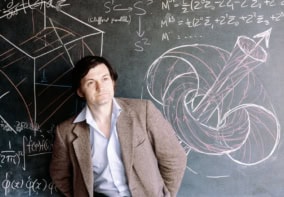

From quarks and complexity to linguistics and ecological diversity, Murray Gell-Mann is a man of many interests, as Peter Rodgers finds out

Murray Gell-Mann’s reputation precedes him as he walks through the lobby of the Shelbourne Hotel in Dublin for an interview with Physics World. Gell-Mann received the Nobel prize in 1969 for his contributions to elementary particle theory, most notably for the development of the quark model, and there are countless stories about how clever he is. “He has a more profound knowledge of a wider range of subjects than anyone living” wrote fellow Nobel laureate Philip Anderson in a review of Gell-Mann’s popular book The Quark and the Jaguar.

In his prime, Gell-Mann enjoyed a “two-decade reign as emperor of elementary particles” according to Sheldon Glashow, also a Nobel laureate in particle theory. But there is another side to him, as Glashow explained in a review of Strange Beauty, a recent biography of Gell-Mann written by George Johnson of the New York Times. “Not only did Gell-Mann devise the lion’s share of today’s particle lore,” wrote Glashow, “but on first acquaintance you would soon learn, through his painfully in-your-face erudition, that he knew far more than you about almost everything, from archaeology, birds and cacti to Yoruban myth and zymology.”

There are countless myths about Gell-Mann, and every time a book or an article by or about him is published, more stories and anecdotes are added to the legend. Indeed there are so many stories about Gell-Mann that it would be easy to write an article about him without ever actually meeting him. And at one stage it looked as if that might happen as Gell-Mann – trying to complete a lecture that he was due to give the following day – cancelled an interview with Irish radio and re-arranged his encounter with Physics World for a second time.

But when Gell-Mann does arrive, it is hard to disagree with Johnson’s claim in the prologue to Strange Beauty that “contrary to so many of the legends, Gell-Mann likes people and conversation”. However, his mood changes towards the end of the interview when the conversation turns to Johnson’s biography. Has he read it? “I have looked through it,” Gell-Mann winces, “but it is so painful.”

So what is the truth about some of the most famous myths? Did Gell-Mann really not write up his Nobel lecture? “I did have a written version of the lecture that I gave in Sweden, but I was not satisfied with it and did not submit it,” he explains. “I tried to write a better one, including an adequate discussion of quarks, and agonized over it for months, but in the end, I did not finish it in time for it to be included in the volume.”

Gell-Mann says that he often agonizes over writing projects. “On many occasions it has delayed my writing up research, often by a year or more. By that time, it has sometimes happened that another theorist has had a similar idea and has written it up more quickly.” Why does he agonize? “I often have a neurotic difficulty with deciding how to put things and in what order. It may stem from my father’s criticism of my writing when I was young – he was a perfectionist and I became one too.”

Quirks and quarks

Another common claim is that Gell-Mann did not actually believe that quarks were real physical entities. “That is baloney,” he says. “I have explained so many times that I believed from the beginning that quarks were confined inside objects like neutrons and protons, and in my early papers on quarks I described how they could be confined either by an infinite mass and infinite binding energy, or by a potential rising to infinity, which is what we believe today to be correct. Unfortunately, I referred to confined quarks as ‘fictitious’, meaning that they could not emerge to be utilized for applications such as catalysing nuclear fusion.” Gell-Mann says that he “did not want to get into debates with philosophers over whether particles that cannot emerge singly can be regarded as real”.

So did Gell-Mann get on with the late Richard Feynman when they were both at Caltech and probably the two most famous physicists in the world? “I was initially a great admirer of Dick Feynman, and I know that he thought highly of me and of my research,” he recalls. “We worked together for a number of years, but I found that he had difficulty thinking in terms of ‘us’. He acted as if the only thing that mattered was his understanding of what was going on. It was all ‘I, I, I,’ and eventually it got on my nerves.” Matters came to a head when Feynman published a book of anecdotes called Surely You’re Joking, Mr Feynman. “Some of the sentences in the book were outrageous and I made him change them in the paperback version.”

Gell-Mann’s contributions to particle physics are immense, as Sidney Coleman of Harvard University made clear in a review of The Quark and the Jaguar: “Strangeness, the renormalization group, the V-A interaction, the conserved vector current, the partially conserved axial current, the eightfold way, current algebra, the quark model, quantum chromodynamics – and this is the shortlist.”

Does Gell-Mann still follow developments in physics? “I do not keep up with the details of particle physics,” he says, “but I try to have a general idea of what is going on.”

When he wrote The Quark and the Jaguar back in the early 1990s, Gell-Mann was confident that superstring theory would ultimately be successful in combining the general theory of relativity with quantum mechanics. Is he still confident that superstring theory – now known as M-theory (see Physics World March 2002 p8) – will ultimately be successful? “I still think that it is very likely,” he replies, “but it is essential to describe M-theory and to extract its predictions.” And does he think that progress in superstring theory is moving fast enough? “You know how it is with human endeavours,” he replies. “Enthusiasm is followed by disappointment and even depression, and then by renewed enthusiasm.”

So when and why did Gell-Mann move away from the simple – if quarks and the Standard Model of particle physics can be called simple – and start getting interested in the complex? “I have been interested in phenomena involving complexity, diversity and evolution since I was a young boy,” he says, “but it so happened that I took up elementary particle theory. Now, at the Santa Fe Institute, I can do research on both the simple and the complex.” Gell-Mann chose the title of his book – The Quark and the Jaguar – to reflect his interest in both the simple and the complex, and also his concerns about sustainability and the maintenance of biological and ecological diversity

So what is complexity? “There are many different definitions of complexity,” he says, “but when we talk about it in ordinary conversation – and in most scientific discourse as well – we really mean what I call ‘effective complexity’. This is the algorithmic information content – a kind of minimum description length – of the regularities of the entity in question.”

Gell-Mann illustrates what he means with his neck tie. “A simple pattern – say one with regimental stripes – has regularities that take only a short time to describe. The regularities of a complex necktie – like one designed by the late Jerry Garcia [leader of the Grateful Dead rock band] – require a much longer description,” he explains. “But how do we know that the regularities we are discussing are those of the pattern? What about the soup stains, wine stains and so on? If you are a dry cleaner, you might be interested in those and not in the pattern.”

Radio astronomy is another example. “We tend to think of music on the radio as regular,” says Gell-Mann, “while static is random. But when researchers at Bell Labs discovered that static tends to come from particular places in the sky, the whole field of radio astronomy opened up.”

Some researchers have dismissed effective complexity as being too context dependent, or even subjective, but Gell-Mann disagrees, pointing out that similar judgements are routinely made in statistical mechanics.

Language

Gell-Mann has always been interested in languages and recently received funding to organize a group of linguists to explore distant relationships among human languages. The idea is to place the acknowledged families of languages – such as Indo-European, Uralic and Austronesian – into “superfamilies” and so on back to a possible proto-language for the whole world. The project also involves archaeologists, physical anthropologists and geneticists.

Gell-Mann confesses that “many professors of historical linguistics claim that this kind of work is unscientific”, but, not surprisingly, he disagrees. Critics of Gell-Mann’s approach claim that the evidence for larger families of languages is too sparse. It is not possible, they say, to establish relationships between different languages that involve “time depths” of greater than the six or seven thousand years.

But if his critics are correct, Gell-Mann counters, then the evidence for the language families that are widely accepted would be marginal. “But we know that is not the case,” he says. “The evidence for Indo-European, Uralic, Austronesian and so on is overwhelming, and there is no reason not to go deeper.”

Gell-Mann explains that the project – which relies both on powerful computer techniques and the expertise of professional linguists – has to cope with the fact that both the meaning and the sound of a word can change over time. “Take the root of the word for ‘woman’ in many Indo-European languages,” he says. “It is ‘gyne’ (as in gynaecology) in ancient Greek, ‘zhena’ in Church Slavic, ‘bean’ (as in banshee) in Irish and ‘kvinna’ in Swedish.”

Final words

Gell-Mann’s interest in words was evident at an early age. He was only 10 years old when he first leafed through a copy of Finnegans Wake – the novel by James Joyce that later provided him with the word “quark” – and was able to study Joyce’s original manuscript for the novel during a visit to Dublin in the middle of last year (see Physics World September 2002 p9).

But if Joyce is one of Gell-Mann’s favourite writers, then his biographer George Johnson is anything but. If you are not Murray Gell-Mann, Johnson’s biography is an engrossing portrait of a brilliant physicist who happens to be a complex and, at times, troubled character. Strange Beauty was greeted by glowing reviews and is more than a match for James Gleick’s acclaimed biography of Gell-Mann’s great rival Feynman.

Gell-Mann, however, was not impressed. “He got many things wrong about physics, about my family and my personal life, and about my motivations in writing papers the way I did. I could so easily have set him straight,” he says. “He even got wrong the part of New York where I lived when I was a baby. A number of reviews were headlined ‘Boy from the Lower East Side’.”

Despite his misgivings about the biography, Gell-Mann has no plans to publish an autobiography, although he might write a book of anecdotes with a collaborator. He is also writing up his Ulam lectures on simplicity, complexity, regularity and randomness – which he gave at the Santa Fe Institute in 1999 – at a popular level.

Gell-Mann also continues to work on at least one physics problem – an interpretation of quantum mechanics that is suitable for quantum cosmology. However, he is no fan of the standard or Copenhagen interpretations of quantum theory. “The idea that quantum mechanics depends on having a physicist outside the system making repeated measurements – or measurements on repeated copies – is clearly absurd when you are talking about the universe,” he says. “Is it imaginable that in the 13 or 14 billion years before human life appeared there was no quantum mechanics? That is ludicrous.”