Robert P Crease discusses a book by a theoretical-physicist-turned-philosopher that seeks to upend some long-standing views

Quantum mechanics, writes the US philosopher Karen Barad, seems to inspire “all the right questions”. So how come we can’t seem to get the answers? Writing specifically about Michael Frayn’s play Copenhagen, for instance, Barad notes that it leaves the audience with the “empty feeling that quantum theory is somehow at once a manifestation of the mystery that keeps us alive and a cruel joke that deprives us of life’s meaning”.

Barad received her PhD in theoretical physics from Stony Brook University (though I do not know her) and pursued a physics career before joining the feminist-studies department at the University of California, Santa Cruz. In 2007 she wrote a book, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, that is fascinating for the vigilance it pays to the philosophical implications of physics. After discovering the book, I’ve made parts of it required reading for my science-philosophy students.

Faulty inheritance

Philosophers are in many ways like scientists, in that each generation inherits various assumptions, concepts and methods that it uses to try to understand our world. Inevitably, some elements prove inadequate, creating paradoxes and mysteries that force us to continually revise that inheritance.

Barad’s book attacks a specific philosophical inheritance known as “representationalism”. It’s the idea that knowledge consists of theories and concepts that represent – but are not connected to – real things such as lumps of metal or ocean waves. At the heart of what’s wrong, Barad argues, is the assumption that knowledge involves a subject over here, an object over there, and a space to be crossed to connect them.

Barad’s alternative position, which is not new, is known as “naturalism”. It’s the view that “we are part of that nature that we seek to understand” – knowers and known are bound up in a single process. What’s novel is that Barad articulates her view from insights into quantum physics. Taking it seriously, she suggests, means that “every aspect of how we understand the world, including ourselves, is changed”.

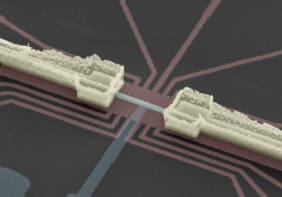

Ambitious stuff. Barad starts her discussion with Niels Bohr’s point that, to understand nature, we interact with it. Barad argues, wielding the double-slit experiment as the classic illustration, that quantum phenomena are events produced by interactions between component parts of nature, including the experimental set-up itself. Barad extends Bohr’s insight using an elaborate analogy involving diffraction (she uses the word interchangeably with interference) to show how experimental practices cannot be subtracted from a result to leave an “objective” residue that was there all along.

Barad, however, finds that Bohr did not go far enough. He wanted to view human beings as part of nature, but ended up treating an experimentalist as a subject who “stands fully formed before the action and chooses a particular apparatus as part of doing an experiment”. In other words, Bohr saw the person doing an experiment as “an external observer, a spectator, removed from the scene of action”.

Barad in fact thinks humans are a bit like quantum phenomena. She regards us as “emergent phenomena like all other physical systems”, who arise within larger configurations of social practices and material worlds. Human cognition and “agency” (the ability to exert force) cannot be ascribed to single, dimensionless consciousnesses but are distributed among and exerted by these configurations. In fact, she doesn’t think “knowing” is exclusive to human subjects; it is “not a human-dependent characteristic”. She calls her position “agental realism”.

Barad’s most remarkable illustration of agency not being located in a single consciousness but distributed in a material context – her “Exhibit A” – is the brittlestar, an invertebrate marine creature that is a relative of the starfish. Brittlestars flee from predators, knowing and acting intelligently without eyes. They do so thanks to arrays of microlenses that collect and focus light on nerve bundles. “Brittlestars don’t have eyes; they are eyes,” Barad writes. “The brittlestar is a living, breathing, metamorphizing optical system” – a live diffraction grating. “For a brittlestar, being and knowing, materiality and intelligibility, substance and form, entail one another,” she says. It is a brilliant use of a scientific image for philosophical effect.

Barad compares her own book to a diffraction grating, producing a design that cannot be understood without taking into account all the individual elements. Skipping over parts, she warns, makes it “difficult to appreciate the intricacies of the pattern”. I’ve left out much of that overall pattern, but many of the book’s intriguing features – and how it puts physics to philosophical effect – appear in the curtailed view I’ve provided.

The critical point

Still, it is a jump from brittlestars to humans; how big a jump? A weak point is that Barad does not fully address the “nature” to which we belong and that we seek to understand. Does it include the entire realm of what it is to be human, including how we enjoy, say, rainbows or are outraged by injustice? If so, naturalism is hardly a position at all, and rather tautological. Or does the word “nature” involve a more scientific conception of the real, what experimental scientists find in the laboratory? If so, then we’re effectively relegating many aspects of human life to secondary status. Barad’s emphasis on the distributed and material character of agency sometimes makes it hard to tell which perspective she is writing from. In fact, that ambiguity led one student of mine to complain (while acknowledging that this is not Barad’s intent) that suddenly “racism, sexism and homophobia are no more problematic than waves grinding rock into sand”.

Barad sometimes writes as though solving long-standing philosophical problems were just a matter of watching what scientists do and heeding the implications. It is indeed impressive how much she accomplishes by following that path. Still, “What do we mean by nature?” is among the right questions that we have to ask.