A major exhibition at the Science Museum in London (and associated book) brings together an impressive collection of Soviet technologies from the birth of the space age, and tells the cultural story of a nation enchanted by the cosmos. James Dacey reviews the exhibition and discovers some of the biggest logistical and political challenges of bringing together the collection

When the Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin visited the Cosmonauts exhibition at the Science Museum in London, he was characteristically blunt, describing it as the story of a “competitor that lost”. Visitors without a direct link to the space race, however, will probably draw very different conclusions from this exhibit and its associated book. Cosmonauts is not so much a story of winners and losers as an incredible tale of what happened when humans left the planet for the first time.

The first steps of Aldrin and his Apollo comrades on the lunar surface marked a pivotal moment in the space race, but Cosmonauts reminds us that the Soviets had their own string of era-defining achievements. These included the first spacecraft to enter orbit (Sputnik, 1957) and reach the Moon (Luna 2, 1959); the first man and woman in space (Yuri Gagarin in 1961, Valentina Tereshkova in 1963); and the first spacewalk (Alexei Leonov, 1965). Chief among the marvels on display here is Tereshkova’s 2.6 tonne Vostok-6 descent module. It is sometimes possible to look at museum artefacts dispassionately, with a slight historical disconnect, but there is nothing abstract about the charred surface of this humble brown sphere: it really did leave our planet and come hurtling back at 27,000 kilometres per hour.

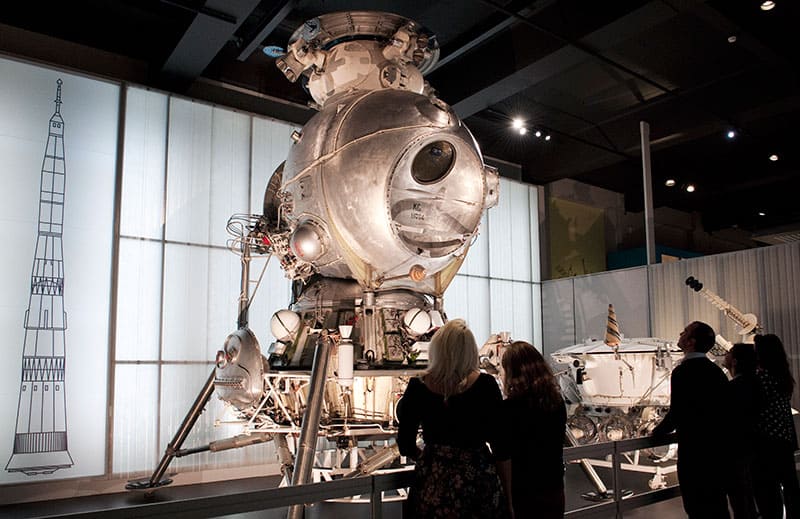

In contrast, the largest item in the Cosmonauts collection – a 3 tonne, 5 m-tall engineering model of the LK-3 lunar lander – remained firmly on the ground. After the death of chief engineer Sergei Korolev in 1966, the Soviet space programme lost its way somewhat, and the LK-3 never put a cosmonaut on the Moon. Still, it looks impressive, with a spherical body and spindly legs that resemble those of a giant metallic insect. It also had to be officially declassified before appearing in the exhibition, as it had previously been kept out of public view at the Moscow Aviation Institute. In fact, the entire crewed lunar programme had been kept secret until 1989.

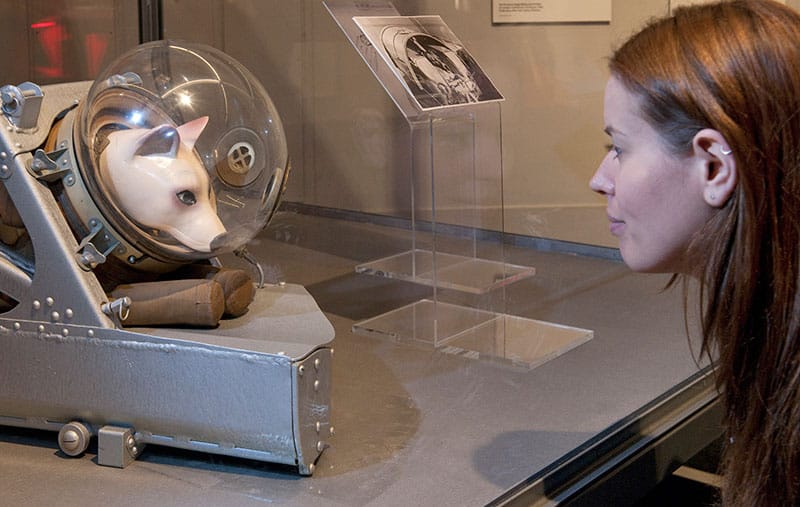

Some of the most fascinating objects in Cosmonauts are the smaller accessories and the stories behind them, such as the first drawing in space (sketched by Leonov on Voskhod 2). Other insights into the cosmonauts’ experience come from the tools meant to help them survive after their descent modules crashed back to Earth: a standard survival kit included both a needle and thread (for repairing clothes) and a pistol (for shooting predatory animals). And an ejector seat used on the earliest Soviet flights, which carried dogs rather than humans, has a certain macabre humour to it: its plastic pooch looks hesitantly out of a plastic bubble hat.

Emma Smith, a member of the curator team, describes Cosmonauts as the most ambitious exhibition the Science Museum has ever undertaken. Part of the reason is that all but two of 150 artefacts were borrowed from Russia, with many coming from closed military enterprises and private collectors. In assembling the collection, the curatorial team made copious trips to Moscow and worked closely with their exhibition partner the State Museum and Exhibition Center (ROSIZO) as well as the British Council and the UK embassy in Moscow.

As well as persuading Russians to part temporarily with their invaluable cultural heritage, the other big challenge was to transport these large heavy objects to the UK without breaking them. In the case of Vostok 6 the challenge became even harder when asbestos was discovered in the heat-proof shielding – a substance forbidden for UK imports. Smith and her team managed to secure an exemption from the UK Health and Safety Executive on the condition that it was transported securely in a sealed environment. She recalls with fondness a training exercise when her team took a giant beach ball – purchased from a leading UK supermarket – wrapped it in cling film and practiced manoeuvring it around the exhibition space. Every little practice helps.

Vostok 6 and several other larger objects were too large to be flown so were transported in 20 m-long trucks by an armed security escort by road across the Finnish border, then by ferry from Helsinki to the UK. “I was quite nervous when we were crossing the Russia–Finland border because it’s quite an unusual object to be transporting,” says Smith. Upon arriving in London, the adventure was far from over as the exhibition is located on the first floor of the museum. Specialists were called in to lift the objects using hoists and gantries and Russian engineers were flown in to help with the reassembly of the LK-3 model.

Cosmonauts also explores Russia’s cultural fascination with space travel. This stretches back to the late 18th century, when the “cosmist” philosophers argued that humanity’s destiny lay in space – the only place that could set us free from the imperfect realities of life on Earth. Later, in the Soviet era, the cultural connection was strengthened by the humble origins of many cosmonauts: both Gagarin and Tereshkova were from rural areas and had parents who worked as labourers. This helps to explain why ordinary citizens felt such a strong link with the missions. A lovely illustration of this is a letter written by a schoolgirl, Maria Kartseva, to Moscow Radio Committee in 1959. In it, she expresses her desire to fly to the Moon in her “warm skiing jacket, felt boots and a warm fur hat”.

Ultimately this is a universal story, and to argue that Cosmonauts makes a case for a Soviet space “victory” is to limit your appreciation of this fine exhibition. It’s a thrilling journey, this business of stepping into the infinite blackness. Why not enjoy the ride?

Cosmonauts: Birth of the Space Age

Science Museum, London

Exhibition runs until 13 March 2016

Scala Arts Publishers £45.00/$75.00hb 256pp

- A version of this article appeared in the December 2015 issue of Physics World.