It’s well known that cities tend to be warmer than surrounding rural areas, as a result of the urban heat island effect. Now research indicates they may also be windier. This “urban wind island” phenomenon sees warmer urban air and the extra roughness created by buildings add energy to the lowest layer of the atmosphere and increase wind speed.

These slightly faster urban winds may be beneficial to city residents. “They could provide a refreshing breeze on hot days and it might promote ventilation of air pollution,” says Arjan Droste from Wageningen University in the Netherlands. The extra zip in the wind might also make small-scale wind turbines more viable in urban areas.

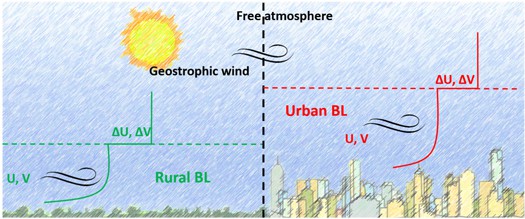

Until now most studies concentrated on localised urban wind effects such as the blasts created by street canyons, or the turbulence close to buildings. But cities cover large areas so to better understand how they affect wider wind patterns, Droste and colleagues modelled the atmospheric boundary layer over urban and rural sites under ten different conditions. The boundary layer is the lowest portion of the atmosphere that is influenced by the Earth’s surface; it’s generally around 1 km deep.

“Enhanced turbulence in the urban area deepens the atmospheric boundary layer, and effectively mixes momentum into the boundary layer from aloft,” the scientists write in their paper in Environmental Research Letters (ERL).

Curiously, the model showed that the urban wind island effect was greatest in areas of low-rise buildings that were up to 12 m high. “Buildings create friction which slows down the wind, so lower buildings are more favourable for the formation of the urban wind island effect,” explains Droste.

Droste and colleagues verified their model using measurements from central London in the UK, the Swiss city of Basel, and Cabauw, a rural area in the Dutch province of Utrecht. Then they used the model to investigate how the urban wind island effect responded to changes in surface roughness.

The team found that over urban areas the boundary layer is usually deeper, and the mean wind speed higher than in surrounding rural areas. The effect is strongest at the beginning of the afternoon, increasing wind speed by an average of 0.5 m/s.

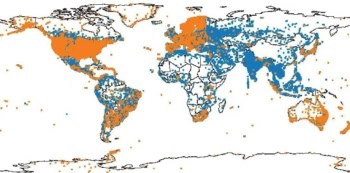

It’s still early days for understanding the urban wind island effect, and there is much work to do. Droste and colleagues are interested in exploring how local meteorology influences urban wind, and how much location matters, for example tropical regions versus temperate, or mountainous areas versus the coast.