Hooke’s masterpiece

By Hamish Johnston

Most physicists are either theorists, who solve problems using mathematics, or experimentalists who make measurements. While the two disciplines are intertwined (except perhaps in fields such as cosmology, where measurements are difficult to make) the two tend to operate in very different ways — which can sometimes lead to tension.

When did this distinction (and occasional animosity) arise in modern science, you might wonder?

One early example is the considerable friction between the greatest theorist and experimentalist of the English Enlightenment — Isaac Newton and Robert Hooke respectively.

Newton remains a celebrity to this day. However, Hooke’s considerable contributions to science (and architecture) remain mostly unsung — with the possible exception of his spring law.

On Thursday evening BBC 4 aired a programme called Robert Hooke: Victim of Genius, which tries to set the record straight. For some reason, the BBC has not made it available for viewing online, so you will have to wait for a repeat.

I came to the conclusion that many of Hooke’s problems were related to his humble beginnings — or more precisely, the fact that Hooke began as an apprentice painter, paid his way through university working as a servant to fellow students, and then earned his living by building scientific equipment for the Royal Society.

When this lowly chap informed the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics that he had formulated the inverse square law of gravitation years before the publication of Principia, Newton is said to have flown into a rage. The two had already sparred over their optical theories, and when Newton took over as president of the Royal Society in 1703 (the year of Hooke’s death), he began erasing all traces of Hooke. Famously, he tossed the only contemporary portrait of Hooke onto a fire.

It would be disingenuous to describe Hooke as a man of modest means — he made a fortune surveying London after the Great Fire — and he was a colleague of many great scientists of the day including Robert Boyle, Edmund Halley and John Flamsteed. Who apparently made liberal use of Hooke’s intellect and experimental skills, sometimes without giving due credit.

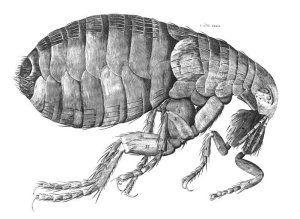

However, Hooke was a man who got his hands dirty building wonderful machines such as vacuum pumps and telescopes. He was also a skilled artist — consider the sketches in his masterpiece Micrographia (above).

In other words he was an experimentalist, and history of physics tends to remember the theorists.

The BBC programme was presented by Oxford’s Allan Chapman, and you can read his essay

England’s Leonardo: Robert Hooke (1635-1703) and the art of experiment in Restoration England on a website dedicated to Robert Hooke that has been set up by Westminster School.