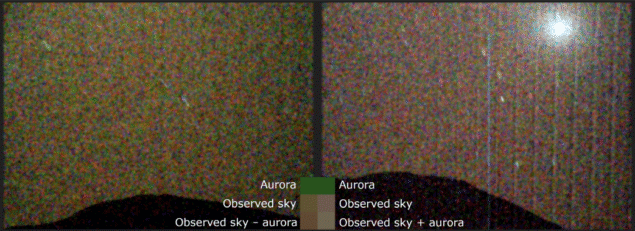

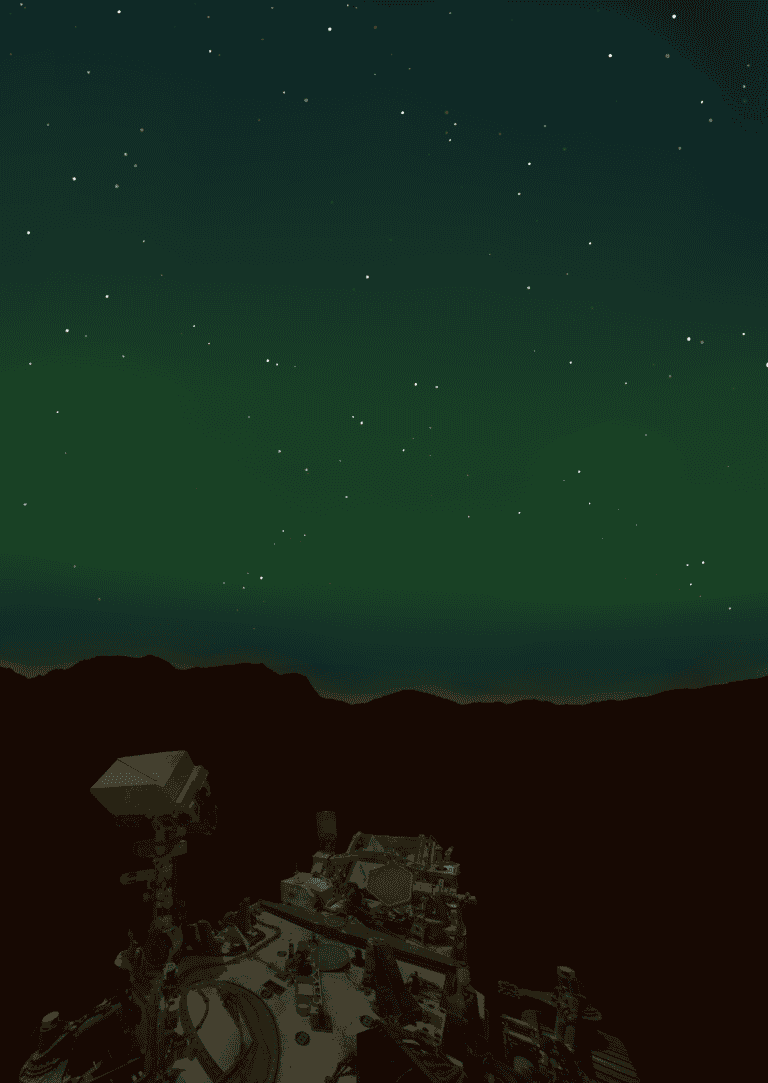

The Mars rover Perseverance has captured the first image of an aurora as seen from the surface of another planet. The visible-light image, which was taken during a solar storm on 18 March 2024, is not as detailed or as colourful as the high-resolution photos of green swirls, blue shadows and pink whorls familiar to aurora aficionados on Earth. Nevertheless, it shows the Martian sky with a distinctly greenish tinge, and the scientists who obtained it say that similar aurorae would likely be visible to future human explorers.

“Kind of like with aurora here on Earth, we need a good solar storm to induce a bright green colour, otherwise our eyes mostly pick up on a faint grey-ish light,” explains Elise Wright Knutsen, a postdoctoral researcher in the Centre for Space Sensors and Systems at the University of Oslo, Norway. The storm Knutsen and her colleagues captured was, she adds, “rather moderate”, and the aurora it produced was probably too faint to see with the naked eye. “But with a camera, or if the event had been more intense, the aurora will appear as a soft green glow covering more or less the whole sky.”

The role of planetary magnetic fields

Aurorae happen when charged particles from the Sun – the solar wind – interact with the magnetic field around a planet. On Earth, this magnetic field is the product of an internal, planetary-scale magnetic dynamo. Mars, however, lost its dynamo (and, with it, its oceans and its thick protective atmosphere) around four billion years ago, so its magnetic field is much weaker. Nevertheless, it retains some residual magnetization in its southern highlands, and its conductive ionosphere affects the shape of the nearby interplanetary magnetic field. Together, these two phenomena give Mars a hybrid magnetosphere too feeble to protect its surface from cosmic rays, but strong enough to generate an aurora.

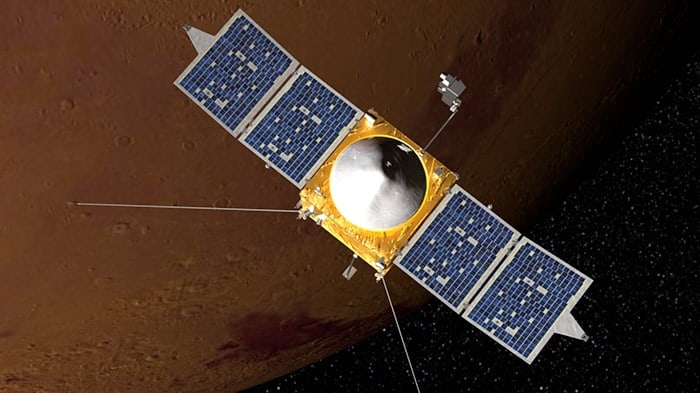

Scientists had previously identified various types of aurorae on Mars (and every other planet with an atmosphere in our solar system) in data from orbiting spacecraft. However, no Mars rover had ever observed an aurora before, and all the orbital aurora observations, from Mars and elsewhere, were at ultraviolet wavelengths.

How to spot an aurora on Mars

According to Knutsen, the lack of visible-light, surface-based aurora observations has several causes. First, the visible-wavelength instruments on Mars rovers are generally designed to observe the planet’s bright “dayside”, not to detect faint emissions on its nightside. Second, rover missions focus primarily on geology, not astronomy. Finally, aurorae are fleeting, and there is too much demand for Perseverance’s instruments to leave them pointing at the sky just in case something interesting happens up there.

“We’ve spent a significant amount of time and effort improving our aurora forecasting abilities,” Knutsen says.

Getting the timing of observations right was the most challenging part, she adds. The clock started whenever solar satellites detected events called coronal mass ejections (CMEs) that create unusually strong pulses of solar wind. Next, researchers at the NASA Community Coordinated Modeling Center simulated how these pulses would propagate through the solar system. Once they posted the simulation results online, Knutsen and her colleagues – an international consortium of scientists in Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, the UK and the US as well as Norway – had a decision to make. Was this CME likely to trigger an aurora bright enough for Perseverance to detect?

Mysterious dust and diffuse aurorae envelop the red planet

If the answer was “yes”, their next step was to request observation time on Perseverance’s SuperCam and Mastcam-Z instruments. Then they had to wait, knowing that although CMEs typically take three days to reach Mars, the simulations are only accurate to within a few hours and the forecast could change at any moment. Even if they got the timing right, the CME might be too weak to trigger an aurora.

“We have to pick the exact time to observe, the whole observation only lasts a few minutes, and we only get one chance to get it right per solar storm,” Knutsen says. “It took three unsuccessful attempts before we got everything right, but when we did, it appeared exactly as we had imagined it: as a diffuse green haze, uniform in all directions.”

Future observations

Writing in Science Advances, Knutsen and colleagues say it should now be possible to investigate how Martian aurorae vary in time and space – information which, they note, is “not easily obtained from orbit with current instrumentation”. They also point out that the visible-light instruments they used tend to be simpler and cheaper than UV ones.

“This discovery will open up new avenues for studying processes of particle transport and magnetosphere dynamics,” Knutsen tells Physics World. “So far we have only reported our very first detection of this green emission, but observations of aurora can tell us a lot about how the Sun’s particles are interacting with Mars’s magnetosphere and upper atmosphere.”