Each year, two million people – mostly children – die from water-borne diseases, such as diarrhoea and cholera, according to the United Nations. The particularly vulnerable include those people trapped in disaster-stricken areas, such as victims of the recent earthquake in Haiti, who struggled to get clean water after damage to water resources. However, a technique that produces drinking water from seawater, using just small amounts of energy, could lead to a portable technology that could help to address this dire situation.

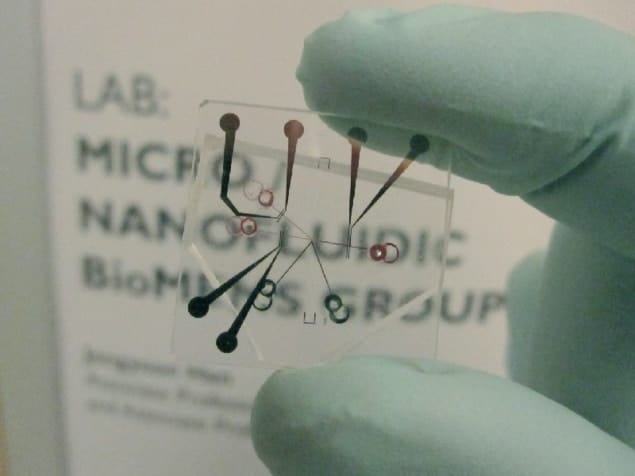

The technique, developed by researchers in the US and Korea, manages to desalinate water using a simple electronic system on a tiny chip. The process starts by passing water along a tiny channel on a polymer chip – with a width of just 500 µm – until it reaches a junction, which then splits off into two separate tubes. By applying an electric potential along one of these tubes, salt ions are dragged towards this channel in the form of brine, while desalinated water flows down the second channel under the force of gravity.

To demonstrate the technique, the researchers created one chip that successfully converted seawater, with a salinity of 30,000 mg/l, into fresh water with a salinity of less than 600 mg/l, which meets the international standards for water purity.

Highly efficient

The technique, dubbed ion concentration polarization (ICP), compares favourably with established methods of water desalination in terms of energy consumption, requiring less than 3.5 Wh/l. Reverse osmosis, for example, which works by forcing seawater through a membrane at high pressures to capture the salt, requires 10–15 Wh/l. And electrodialysis, which works by transporting salt ions from one solution to another by means of ion-exchange membranes, requires 5 Wh/l.

In addition to removing salts, ICP can also remove potentially harmful larger molecules such as cells, viruses and bacteria. Reverse osmosis and electrodialysis can also remove these particles too but, in both cases, the membranes become heavily clogged by these particles.

The next challenge for the researchers is to scale up their device into a viable technology. Because one unit produces just 10 μl per minute, the researchers estimate that they will need 10,000 combined units to produce a useful amount of water, while keeping the device portable – they estimate it would be 30×20 cm.

Scaling up

Sung Jae Kim, one of the researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, tells physicsworld.com that building a larger device should be relatively straightforward, and they will have produced a 100-unit device within two years. “We have already experienced a lot of interest from companies – we welcome discussions, but we need first to undergo more testing,” he says. One important aspect is to ensure that all dangerous hydrocarbons and heavy metals are also removed from the seawater, which is not guaranteed with the existing device.

Mark Shannon, a water purification researcher at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign sees great potential in the new technique. “The people of first benefit will be travellers in the developing world, and small scale medical clinics and emergency shelters and orphanages in times of crisis, such as Haiti.”

Shannon agrees, however, that more development is needed to ensure the purity of the desalinated water. “You would still likely need a barrier such as a nanofiltration membrane to ensure near zero pathogens coming through, which is essential for highly contagious enteric viruses and microbes like cholera that can cause severe illness and death if any gets through.”

This research is published in Nature Nanotechnology.