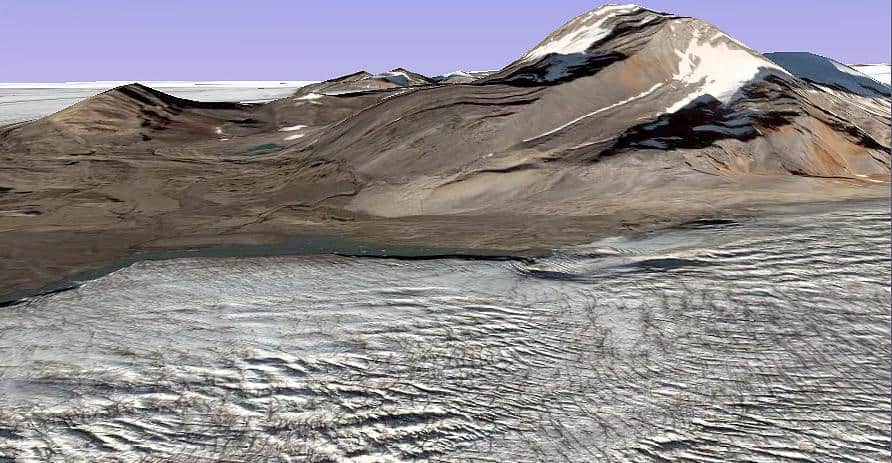

Svalbard Credit: NASA

By James Dacey

Where do we come from? Are we alone? Where are we going? They’re certainly not shying away from the big questions here at the AAAS conference in San Diego. This morning we were celebrating 50 Years of Astrobiology, which is basically the study of the origin and evolution of life on Earth and the search for signs of extraterrestrial life. The research is about as multidisciplinary as you can get drawing on expertise from astronomy, physics, biology, chemistry, geology, and the planetary sciences at the very least.

As interesting as those big questions are, however, I’m usually left frustrated by the vagueness of the actual research. The scientists seem to be staring hard at images and spectra from planets in search of signs of habitable conditions like on Earth, but they don’t really seem to know what they’re looking for. “We can’t say exactly what the conditions necessary for life are. We don’t know whether extraterrestrial life would have evolved in the same way. We don’t really know where to look,” they say.

Well this morning I was pleased to encounter one astro-scientist who seemed a lot less defeatist and was taking a much more down to Earth approach to the search for extraterrestrial life. Pamela Conrad, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, spends her days surveying desolate places on Earth in search of key indicators of habitability. In essence, she goes out into the field and assesses the large-scale physics and chemistry of a remote location before moving in to see whether the site can support life.

In her talk she described one adventure that took her to the remote archipelago of Svalbard, located between mainland Norway and the North Pole. After extensive surveying, Conrad came to conclude that a range of factors including temperatures, light, and even the steepness of slopes had an influence over which parts of the land could support life. One interesting factor is the type of underlying geology – dolerite, an igneous rock, is a good place for life on Svalbard because it can warm up easily then contain heat over time.

And this research is more than speculative because the findings could be used in NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) mission, which is due to launch in 2011. Once the craft has landed, a NASA rover will collect samples to see whether the planet could have supported life at some point in its history. It is important, therefore, to choose a site that at least has a fighting chance of being habitable – that is assuming we want to find those little green men!