In 2022, more than 10.5 million people fell ill with tuberculosis (TB) and an estimated 1.3 million people died from this curable and preventable disease. TB is currently diagnosed using clinical evaluations and lab tests. While spit (sputum) tests and chest X-rays are common, a physician may also recommend a PET scan.

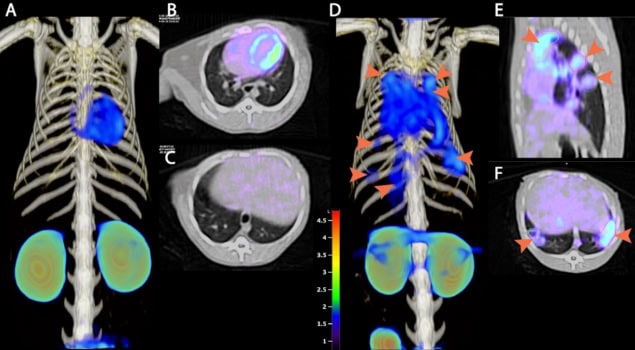

Current PET scans use radiotracers that could indicate TB or other diseases. A PET scan that targets TB bacteria specifically could enable more effective treatment, say researchers at the Universities of Oxford and Pittsburgh, the Rosalind Franklin Institute and the NIH.

“TB normally requires quite long treatment regimens of many months, and it can be tricky for patients to stay enrolled in these,” explains Benjamin Davis, science director for next generation chemistry at the Rosalind Franklin Institute and a professor of chemical biology at the University of Oxford. “The ability now to readily track the disease and convince a patient to stay engaged and/or for the physician to know that treatment is complete we think could prove very valuable.”

Davis and his team have developed a radiotracer, called FDT (2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxytrehalose), that is taken up by live tuberculosis bacteria. FDT-PET scans show signal where tuberculosis bacteria are active in a patient’s lungs and measure the metabolic activity of the bacteria, which should decrease as a patient receives treatment.

“We came up with a way of designing a selective sugar for tuberculosis by understanding the enzymology of the cell wall of TB,” Davis says. “Specifically, we target enzymes in the cell wall that modify FDT, so that it effectively embeds itself selectively into the bacterium. If you like, this is a sort of self-painting mechanism where we get the pathogen to use its own enzymes to modify FDT and so ‘paint itself’ with our radiotracer.”

The researchers have characterized FDT and tested the radiotracer in preclinical trials in rabbits and non-human primates. Phase I clinical trials in humans are set to begin in the next year or so. “We are in the process of identifying partners and sites as well as addressing the differing modes of trial registration in corresponding countries,” says Davis.

PET scans could help develop shorter TB treatments

Another benefit of FDT is that it can be produced from FDG – a common PET radiotracer – without specialist expertise. FDT could thus be a viable option in low- and middle-income countries with less developed healthcare systems, the researchers say, though it does require that a hospital have a PET scanner.

Writing in a press release, Clifton Barry III from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the NIH, says: “FDT will enable us to assess in real time whether the TB bacteria remain viable in patients who are receiving treatment, rather than having to wait to see whether or not they relapse with active disease. This means FDT could add significant value to clinical trials of new drugs, transforming the way they are tested for use in the clinic.”

The research is published in Nature Communications.