Kate Gardner reviews Queen of Codes: the Secret Life of Emily Anderson, Britain’s Greatest Female Codebreaker by Jackie Uí Chionna

It is strange to think that for decades after the Second World War, most British people were not aware of the important role played by codebreakers at the Buckinghamshire country house, Bletchley Park. While there had been rumours about the UK’s Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) – later renamed Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) – since its inception in 1920, it wasn’t until the 1990s, when some records were declassified, that the pivotal actions of the secret organization came to light. Suddenly, there was a flood of memoirs, histories and biographies; mathematician Alan Turing became a household name; and Bletchley Park became a popular tourist destination as a museum dedicated to its wartime role.

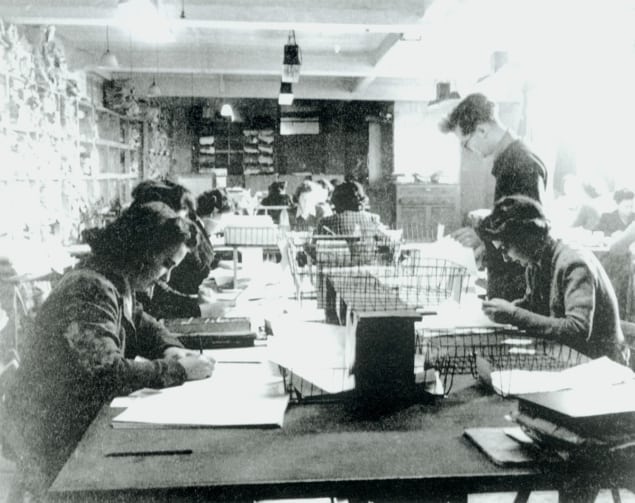

With this influx of revealed secrets, something that may have escaped public notice was that those memoirs were invariably written by men, and the names that became semi-well-known alongside Turing were also all men. But by 1945, three-quarters of the staff at Bletchley Park were women – many of them skilled codebreakers themselves, sometimes running teams and departments. So who were these women and why don’t we know about them?

Jackie Uí Chionna – a historian based in Ireland – has begun to fill this void with her new biography of Irish linguist and codebreaker Emily Anderson. Queen of Codes: the Secret Life of Emily Anderson, Britain’s Greatest Female Codebreaker describes how Anderson – born in 1891 – was raised on the grounds of Queen’s College, Galway (now the University of Galway) by her parents Alexander Anderson, a physicist, and Emily Gertrude Anderson, a suffragist. Though Anderson chose to pursue modern languages – she was fluent in German, French and Italian, and studied in Germany after graduating from University College, Galway – she was also skilled in mathematics and the classics.

It was an irresistible combination for her recruitment in 1917 into MI1(b), a British military intelligence organization created during the First World War. Anderson’s family publicly supported British rule over Ireland, which at the time was a key factor if an Irish citizen was to be hired for a British military role. The Easter Rising of 1916 – when Irish republicans led a rebellion against British rule – had triggered political discontent that would later, in 1919, erupt into the Irish War of Independence.

When Anderson was approached by MI1(b) to become a codebreaker, she was only 26 and had just returned to University College, Galway to take up a professorship. She was set for a glittering academic career, so she only accepted a role with the Foreign Office “for the duration of the war”. However, she ended up staying with them for the remainder of her working life.

After the First World War, Anderson was asked to remain in her codebreaking role. She was the only woman hired for the newly created GC&CS at the level of junior assistant (a deceptive title, as she was in fact a codebreaker, not an administrator or interpreter). However, she did not accept the job until it was agreed that she would be paid at the same rate as men for the role. This was an unprecedented demand and shows how exceptional her skills must have been in her first years of learning the art of codebreaking.

While the story of Anderson joining GC&CS is fascinating, what is sadly lacking in this memoir is detail about codebreaking at this time. Uí Chionna explains some basic concepts such as cyphers and cribs but I would have liked to learn more about exactly what Anderson and her colleagues did, especially in those early years. In fairness, Uí Chionna is hampered by all the records of MI1(b) having been destroyed in 1920. This, coupled with the almost entire absence of surviving personal correspondence to or from Anderson, does at times make Queen of Codes feel like it is itself an exercise in codebreaking, piecing together the clues of Anderson’s life from the fragments available.

What the public saw

This lack of available sources would leave Uí Chionna with a rather slim pool of facts about Anderson were it not for her having, remarkably, a whole second career alongside her secret one.

In 1923 she became the head of the Italian diplomatic section of GC&CS, where she and her team decoded diplomatic telegrams between the Italian government and its military. Anderson felt Italian “wasn’t her best language” so in her free time she set about translating Benedetto Croce’s Goethe – a work in Italian about the German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe – into English.

Though it may have begun as a skill-honing exercise, Anderson’s translation of Goethe was published in 1923. She followed this up with a challenge that combined all her linguistic and codebreaking skills but, crucially, one that she was able to perform publicly and receive credit for – she decided to track down, translate and publish all the letters of the composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Mozart (and some of his family) wrote letters in Italian and German, and in codes of sorts. As Anderson herself described them, there are “passages which are curiously involved, words written backwards, phrases reversed [and many of them] are untidily written, larded with erasures and splashed with ink-blots”. Not only did translating the letters take work, tracking them down required extensive travel to mainland Europe, which was not always straightforward in the 1930s and Anderson almost certainly took advantage of contacts she made through her more secretive line of work.

In 1938 the three volumes of Letters of Mozart and His Family were published to great acclaim and, indeed, are still a key reference work. Anderson enjoyed minor fame as a musicologist and decided to follow this up with a translation of the complete letters of Ludwig van Beethoven. But this project was interrupted by the Second World War.

Back to secrets

The chapters about Anderson’s time at Bletchley Park (1939–1940), and then at the Combined Bureau Middle East (1940–1943), are where Uí Chionna provides the most detail of Anderson’s “day job” of codebreaking – no doubt because these records have survived and been made public. From her base in Cairo, Anderson broke Italian codebooks and provided intelligence that changed the course of the war in North Africa – and she was awarded an OBE for this work. In 1943 she returned to the diplomatic section of GC&CS at its new offices in Berkeley Street, London, and remained there until she retired in 1950.

It is to Uí Chionna’s credit that she discusses, but does not linger on, the question of Anderson’s sexuality. She never married (indeed, she would not have been able to retain her job if she had done so) and there is some limited evidence of her having relationships with women. Being gay would in some ways have made her a perfect candidate for military intelligence, as the legal and social situation at the time would have necessitated a life of discretion. But we cannot know for sure about this aspect of Anderson’s private life, and Uí Chionna doesn’t press the point.

What Uí Chionna does spend some time analysing is why female war-time codebreakers never wrote memoirs or spoke about their work publicly, as so many of their male counterparts did. The main reason, she argues, is that men felt a need to prove what they had been doing during the wars. Women could say they’d become civil servants for the duration and no-one would think twice of it, but men were expected to have gone overseas to fight. Men with money and a private education – which was the case for many who were recruited to GC&CS – were expected to have had a commission, to have held military titles and earned medals. It could cause real, lasting damage to a man’s reputation if word got out that he had stayed in Britain, even with cover stories about vital work for the Foreign Office.

For my taste, Queen of Codes spends a little too much of its time on Anderson’s musicology research and speculation about her relationships with her immediate family. It is also repetitive in places and, conversely, hides some fascinating details in its extensive endnotes. But on the whole, this is a thoroughly researched and highly readable account of a woman who may have appeared to the world as the epitome of ordinary, but was in truth anything but.

- 2023 Headline 418 pp £25hb