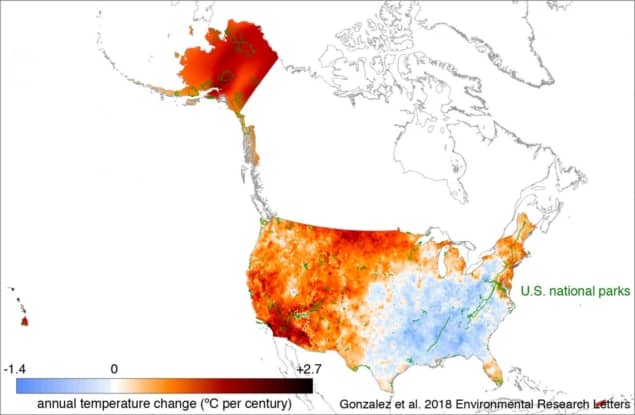

National parks in the US are typically more exposed to changes in climate than other parts of the country, according to a study of all 417 sites. Between 1895 and 2010, historical mean annual temperature of the national park area increased at double the average US rate.

“The disproportionate exposure of national parks derives from the location of extensive park areas in extreme environments,” says Patrick Gonzalez of the University of California Berkeley, US. “A higher fraction of the national park area is in the Arctic, at high elevations, and in the arid southwestern US.”

By the end of the century, rising levels of greenhouse gas emissions could push up average temperatures in US national parks – which cover 4% of the country – by as much as 9 °C, according to estimates by the researchers.

“Changes could occur faster than the abilities of many plant and animal species to migrate to stay in suitable climate spaces,” says Gonzalez, who carried out the research with colleagues from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, US.

Consequences of rising temperatures include increased wildfire in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, extensive mortality of Joshua trees (Yucca brevifolia) in Joshua Tree National Park, California, and possible extirpation of the pika, a small alpine mammal, from Lassen Volcanic National Park, California.

Records show that annual precipitation has declined significantly across 12% of the national park area. Annual rainfall across the US as a whole has increased, in contrast.

The team reports that national parks in Alaska are most exposed to temperature increases while Hawaii, the Virgin Islands, and the southwestern US are most exposed to precipitation decreases.

The extent to which these scenarios play out is considered to be strongly dependent on the amount of greenhouse gases emitted from vehicles, power plants, and other human sources between now and 2100.

“Compared with the highest emissions scenario, reduced emissions would lower the rate of temperature increase in the national parks by one-half to two-thirds by 2100,” says Gonzalez.

The scientists hope their findings will help develop adaptation measures for fire management and invasive species control, and other ways to protect parks against hotter and drier conditions.

“The next steps involve helping national parks apply the data to specific issues,” says Gonzalez. “For example, based on the analyses of climate change vulnerability, parks can preemptively target prescribed burning and manage wildland fire to reduce future fire risks.”

The team published their findings in Environmental Research Letters (ERL).