The US should begin planning a next generation electron-ion collider (EIC) to study the structure of protons and neutrons in unprecedented detail. That is according to a 15-strong committee of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. It’s 115-page report, commissioned by the US Department of Energy (DOE), says that an EIC with high energy and luminosity as well as highly-polarized electron and ion beams “would be unique to greatly further our understanding of visible matter”.

The science that can be addressed by an EIC is compelling, fundamental, and timely

Gordon Baym

By accelerating and smashing together electrons with protons or ions, an EIC, the report says, would address profound questions about nucleons such as how their mass and spin arise and what is the role of gluons, the carrier of the strong force. The report calls for a machine that can accelerate electrons up to 20 GeV and ions with an energy up to 300 GeV at high luminosity.

“The science that can be addressed by an EIC is compelling, fundamental, and timely,” says Gordon Baym from the University of at Urbana-Champaign, who co-chaired the committee. “The realization of an EIC is absolutely crucial to maintaining the health of the field of US nuclear physics and would open up new areas of scientific investigation.”

That view is backed up by panel member Richard Milner, a physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He told a press briefing that the EIC “would have a substantial impact on US accelerator science, and in the production of breakthroughs in understanding materials and in life science”.

Compelling questions

The committee emphasizes that no specific design for the facility is under way and that the committee’s remit did not include any estimate of the US EIC’s costs or location. However, the long-range plan for nuclear physics — as set out in 2015 by the DOE and the National Science Foundation — identifies construction of a high-luminosity polarized EIC as the highest priority following the completion of Michigan State University’s Facility for Rare Isotope Beams in 2020.

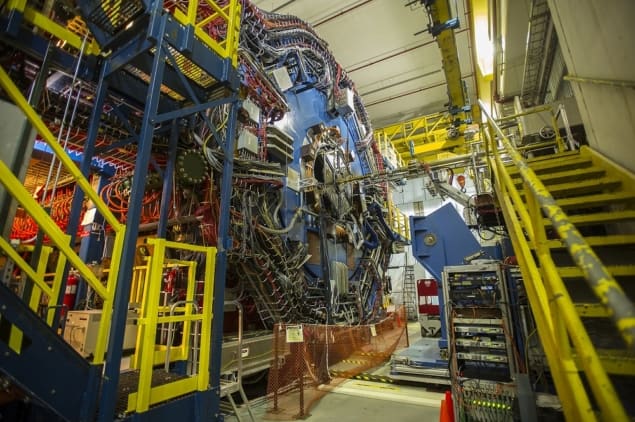

Indeed, the panel asserts that significant and relevant accelerator infrastructure and expertise already exists in the US. The Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) operates the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider, which smashes together heavy ions to study quark-gluon plasma, while the Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Laboratory’s recently upgraded Continuous Beam Accelerator Facility accelerates electrons before firing them into fixed targets. The spin of a proton

The report notes that both labs have proposed design concepts for an EIC “that can use existing infrastructure and both laboratories have significant accelerator expertise and experience”. However, it cautions that “neither of the existing designs can fully deliver on the three compelling science questions” that the EIC would need to address.

Stuart Henderson, director of the Jefferson Lab, BNL director Doon Gibbs and Bernd Surrow from Temple University, who is chair of the electron ion collider user group, note in a joint statement that they are “very pleased” with the report’s conclusions. “Just as studies of fundamental particles and forces have driven scientific, technological, and economic advances for the past century -from the discovery of the electrons that power modern life to the understanding of the structure of the cosmos [so] research conducted with an EIC will spark innovation and enable widespread technological advances,” they note.

China is the only other country that has tentative plans for such a facility, but it would be much lower in energy and intensity that the US machine. “At the moment we are the only one,” panel co-chair Ani Aprahamian from the University of Notre Dame told Physics World. “That would ensure global leadership for this project.”