The Sahara’s spread is now established. Its sands are on the march. The desert is growing, thanks to climate change.

In the last century the region of the Sahara technically defined as desert has increased by at least 10%. And the area that becomes technically desert – with less than 100mm of rain a year – has increased in summer, the wet season, over the same period by 16%.

And if climate change is at work in northern Africa, the same may hold true for some of the world’s other deserts as well, researchers warn.

US meteorologists report in the Journal of Climate that they looked at data from the years 1920 to 2013, to explore the annual trends.

Deserts are natural geographical features with no fixed boundaries: parts of them can bloom in rainier years, and support crops and even foraging animals, only to become extreme arid zones a year or two later.

“The Chad Basin falls in the region where the Sahara has crept southward. And the lake is drying out. It’s a very visible footprint of reduced rainfall not just locally, but across the whole region”

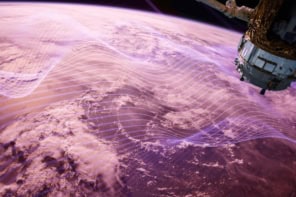

Deserts exist because of the natural circulation of the atmosphere: air rises at the equator and descends in the subtropics to flow back to the equator nearer ground level to establish a pattern of low precipitation: weather experts call this phenomenon the Hadley circulation, after the 18th century British natural philosopher George Hadley.

“Climate change is likely to widen the Hadley circulation causing northward advance of the subtropical deserts,” said Sumant Nigam, a professor of atmospheric and oceanic science at the University of Maryland, one of the authors of the study. “The southward creep of the Sahara however suggests that additional mechanisms are at work as well.”

The other factors probably linked to the shifts in the Sahara sands include a natural climate cycle known to oceanographers and meteorologists as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation.

Overlapping patterns

The headache for climate scientists is to distinguish one natural pattern of change from another, more alarming trend as a consequence of climate change, triggered by global warming as a consequence of the ever-increasing use of fossil fuels by human economies.

And such dissections are not simple: the Sahara expands in the arid winter and shrinks a little with the summer rains. Between the shifting dunes of the Sahara and the fertile savannas of tropical Africa lies the Sahel, a region that straddles 14 nations, from Senegal on the Atlantic coast, through Mali and Chad, to Ethiopia on the Red Sea.

Researchers have repeatedly warned that climate change could bring more famine to this precarious region. But other scientists have detected a trend towards increased rainfall that could make parts of the Sahel flourish again with climate change.

The latest study suggests that on the evidence of water levels in Lake Chad, overall conditions could become harsher for the meagre grasslands and impoverished communities of the Sahel.

Century-long trend

“The Chad Basin falls in the region where the Sahara has crept southward. And the lake is drying out. It’s a very visible footprint of reduced rainfall not just locally, but across the whole region,” said Professor Nigam. The scientists attribute about a third of the shift in the desert’s regime to human-induced climate change, the rest to other cyclic weather patterns.

Researchers have been examining desertification for decades, but this paper is claimed as the first to establish a trend over most of a century, according to Natalie Thomas of the University of Maryland, who led the study.

“Our priority was to document the long-term trends in rainfall and temperature in the Sahara. Our next step is to look at what is driving these trends, for the Sahara and elsewhere,” she said.

“We have already started looking at seasonal temperature trends over North America, for example. Here, winters are getting warmer but summers are about the same. In Africa, it’s the opposite – winters are holding steady but summers are getting warmer. So the stresses in Africa are already more severe.”

- This report was first published in Climate News Network