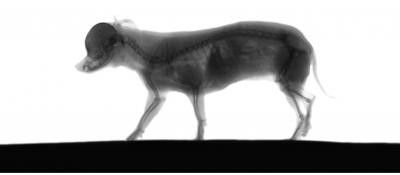

Chihuahua pacing, captured by X-ray video (Courtesy: Martin Fischer)

By James Dacey

They have been our best friends for a long time, so surely we know everything there is to know about dogs. Wrong!

According to researchers in Germany we still have a very patchy knowledge of how dogs move. Of course, we know they scamper along on four legs, occasionally balancing on their back two when they decide to press their muddied front paws against your freshly cleaned shirt. But apparently we are still thin on details when it comes to the precise sequence of movements within their locomotive system.

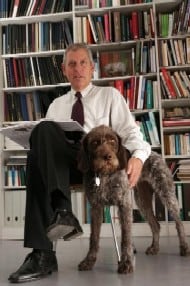

To redress this situation, zoologist Martin Fischer (see picture, right) and colleagues at the University of Jena in Germany have carried out what they claim is the most extensive survey to date of dog movement. They have studied in fine detail the motions of 327 dogs from 32 different breeds by deploying a variety of imaging technologies.

The dogs were filmed from the front and side using high-speed cameras as the animals walked using two different gaits. Following this, the dogs’ movements were captured in 3D by attaching reflecting markers to different parts their bodies before the researchers filmed them using infrared cameras. Then finally, to build a picture of the dogs’ skeletal movements, the researchers recorded the moving dogs using a high-speed X-ray video system.

One interesting discovery to emerge from the X-ray footage is that regardless of the total length a dog’s legs, its upper leg is always the same length – and this appears to be important in linking the movements of the shoulders with the lower legs. For this reason, the researchers conclude that dogs of all sizes run very similarly, whether they are a greyhound or a Schnauzer.

Another key finding relates to how different parts of a dog’s anatomy correlate with each other to enable the front and back legs to move in circular motions. Fischer and his team found that the shoulder blades and the thighs act as centres of rotation for the front and back legs, which contradicts earlier studies that had located these centres at the shoulder joint and hip.

Fischer’s group has compiled its findings and images in a newly published book, Dogs in Motion, which the researchers hope will also be of interest beyond the scientific community. “We explicitly want to reach all dog owners and people who love dogs in general,” says Fischer.

Meanwhile, in other dog-related news, a pair of researchers at Harvard University have used high-speed video combined with X-ray footage to study another aspect of canine motion – how dogs drink. Alfred Crompton and Catherine Musinsky have shown that dogs take the same approach as their arch rivals, cats, when lapping up liquids by allowing water to adhere to the tips of their tongues. Earlier work had suggested that dogs simply “scooped up” water with vigorous swipes of the tongue. Crompton and Musinsky describe their work in a paper recently published in the journal Biology Letters, and you can see the dog-drinking action in this related video.