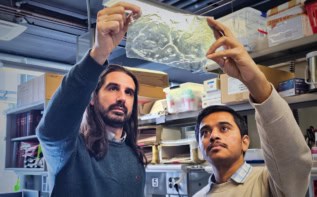

Scientists have invented the aquatic equivalent of the electronic integrated circuit. Todd Thorsen and colleagues at the California Institute of Technology in the US have made a "microfluidic chip" by carving micrometre-sized valves and channels in a slice of silicon-based compound. By directing water along these channels, the chips could be used to manipulate tiny amounts of substance for biological analysis. They could also be used to make a new kind of liquid display (T Thorsen et al. Science to be published).

Biologists have already started to use microfluidic systems to scale down a number of laboratory techniques, but to date these systems have been stand-alone devices. On the other hand, integrated workstations for biologists take up entire laboratories and are expensive and time-consuming to operate. In contrast, Thorsen and colleagues used established lithographic techniques to produce two microfluidic devices from single slabs of polydimethylsiloxane that have an area of just a few square centimetres and can be used to carry out a range of operations.

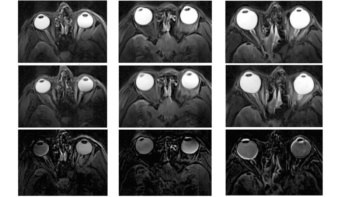

The researchers used their first chip as a memory device. It consists of 1000 cells, arranged in a grid of 25 rows and 40 columns. Each cell serves as a binary bit and is initially full of a sample liquid. To add data to the device a micromechanical valve is opened in every cell within the first column, allowing the contents of each cell – if it is to be set to zero – to be flushed out by a stream of water passing along the respective row. This process is repeated for each column in the grid.

Thorsen and co-workers’ real innovation was being able to restrict the number of electrical inputs needed to control the device. Rather than control the flow of water in each row and column using a separate valve, the researchers arranged groups of valves across multiple channels. In principle, this technology can be easily scaled up since an increase in the number of electrical inputs permits an exponential increase in the number of water channels.

To demonstrate the principles of the chip, the researchers loaded dye into each cell and flushed out the dye from those cells needed to produce the letters “CIT”. In this way, the chip can function as a display, and has the advantage that it requires very little power to retain an image.

The researchers designed the second chip so that it can perform more complex operations, allowing them to study many copies of the same chemical reaction. Two different sample liquids are loaded into each cell and initially separated using a barrier valve. These valves can be turned on and off individually and the contents of each cell inspected one at a time.