So what is the site about?

If you think you’re pretty knowledgeable about the history of space exploration, then this blog will make you think again. It will also send you down one of those Internet “rabbit holes” that spits you out, several hours later, with a newfound appreciation for a subject and a disquieting sense of disbelief about what time it is. (You have been warned.) The person responsible for this particular rabbit hole is the science writer and space aficionado David S F Portree, a veteran of the science blogosphere whose previous sites include the similarly themed Beyond Apollo, which was part of Wired magazine’s science blog network until earlier this year. Like Beyond Apollo, Portree’s new site focuses on the lesser-known aspects of space exploration, including missions and programmes that never got off the ground.

Isn’t that a bit of a downer?

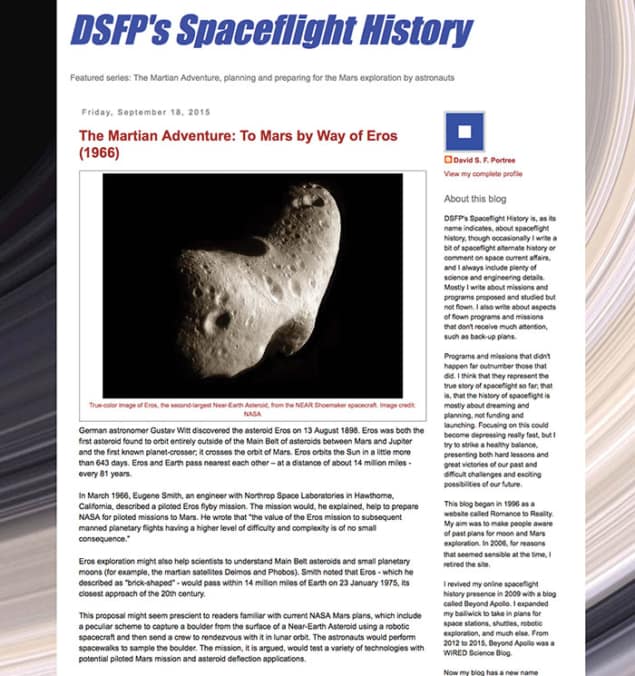

“The history of spaceflight is mostly about dreaming and planning, not funding and launching,” Portree writes. “Focusing on this could become depressing really fast, but I try to strike a healthy balance, presenting both the hard lessons and great victories of our past, and the difficult challenges and exciting possibilities of our future.” It is also interesting to see how particular dreams and plans have cropped up repeatedly (albeit with variations) in the decades since humans began venturing outside the Earth’s atmosphere. For example, NASA’s current plans for capturing an asteroid and landing astronauts on it are reminiscent of a 1966 proposal by one Eugene Smith, an engineer at Northrop Space Laboratories. As Portree explains, Smith pointed out that the asteroid Eros was due to make a close approach to the Earth on 23 January 1975, and suggested that a flyby might make good practice for a future Mars mission.

Who is it aimed at?

The posts on DSFP’s Spaceflight History are written in clear, accessible prose, and most of the physics in them (orbital mechanics, some kinematics, bits of astrophysics and planetary science) is not hard to grasp, at least on a conceptual level. Some of the historical, political and spacecraft-engineering details do get rather technical, however, and you’ll need a high tolerance for acronyms and mission numbers to get through some of the longer, more complex essays. In short, this is a blog for people whose interest in space exploration goes beyond pretty pictures and dramatic stories, although there are plenty of those, too.

Anything else?

Now and then, Portree pokes his nose into topics with a more tangential connection to spaceflight. In one of these, he speculates on what would have happened if astronomers had discovered Pluto in the late 1970s, rather than in 1930. This alternative version of history is plausible, Portree notes, because “only a series of astronomical errors led us to believe that a planet might exist beyond Neptune”. Without those errors, early 20th-century astronomers would have had no reason to hunt for an additional planet, and the object we know as Pluto would probably have been found in 1978 (together with its moon, Charon, which was in fact discovered that year). At that point, we would have realized immediately that Pluto was too small to be a planet – thus avoiding the “dwarf planet” controversy entirely.

Can you give me a sample quote?

From an August 2015 post entitled “Failure was an option: what if Apollo astronauts could not ride the Saturn V rocket?”: “The Saturn V was the largest rocket ever developed. It had engines of unprecedented scale and power: the F-1 engines in the 33-foot-diameter S-IC first stage, which burned RP-1 kerosene fuel and liquid oxygen, remain today the largest ever flown. The J-2 engines in the top two stages, the 33-foot-diameter S-II second stage and the 22-foot-diameter S-IVB stage, gulped down temperamental liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants. Cautious engineers could see many opportunities for trouble, and they were aware that problems they could not foresee might be the most difficult to solve. Many believed that NASA should have in place backup plans in case the Saturn V suffered development delays.”

- Enjoy the rest of the November 2015 issue of Physics World in our digital magazine or via the Physics World app for any iOS or Android smartphone or tablet. Membership of the Institute of Physics required