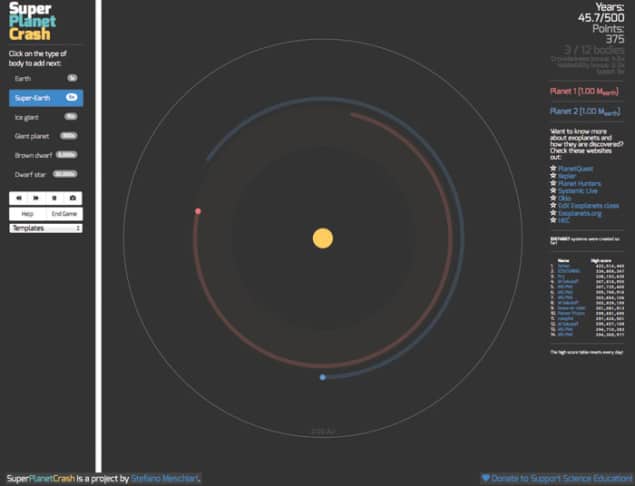

URL: www.stefanom.org/spc

So what is the site about?

Super Planet Crash is a deceptively simple game based on the dynamics of planetary systems. Players start out with a single Earth-sized planet orbiting a Sun-sized star and gain points by adding additional celestial bodies. Bigger objects such as dwarf stars, brown-dwarf planets and gas-giant planets earn more points than smaller ones like ice giants and super-Earths, but be warned: adding the wrong planets at the wrong time or in the wrong places will quickly lead to chaotic behaviour. If your planets crash into each other and/or go rocketing off beyond a certain distance (currently set, somewhat arbitrarily, at 2 AU – twice the distance between the Earth and the Sun), you’ll lose the game and have to start again.

Who is behind it?

The creator of Super Planet Crash, Stefano Meschiari, is a PhD student at the University of Texas at Austin in the US. As part of his “day job”, he maintains a scientific software package called Systemic Console that astronomers use to identify potential exoplanet signals within data sets acquired via Doppler observations of stars. After creating a stripped-down version of Systemic designed for educational use, Meschiari decided that his next project would be even more outreach-oriented. “I had been thinking for a long time about how to use my expertise developing Systemic to create an outreach game that would be appealing to a larger audience,” he told Physics World, adding that he wanted “something that would be fun and easily understandable at a more visceral level than Systemic”.

How much physics is involved?

The science behind the “digital orrery” simulation is pretty basic – these are strictly Newtonian systems, with no adjustments for general relativity. It is also not currently possible to extract numerical data (such as orbital velocities or distances) from games or to “rewind” to the moment just before a crash to study the collision dynamics in more detail. However, Meschiari says that the current game (which has already been played millions of times) is essentially a prototype. He hopes to add more features in the future, and he and some colleagues have applied for funding to develop the game into a full package of “edu-tainment” applications. In the meantime, though, Meschiari hopes that the game will work like a “gateway drug”, stimulating players to learn more about gravity and exoplanets.

What’s it like to play?

Addictive, if sometimes frustrating. To achieve a high score, you really need to chuck a dwarf star into the mix. But while certain binary systems – particularly those where the original star and the added dwarf star are very close together – produce stable orbits, getting there requires “some art and some luck”, Meschiari says. A lot depends on the position of the first planet, which is generated by the game and is therefore random rather than player-determined; hence, in some games, the odds are stacked against you from the start. However, that is perhaps the point, since in real life, as in the game, not all planetary systems are created equal. For example, we do not observe many quadruple-star systems precisely because they are much more likely than binaries to be unstable. And if your reviewer’s efforts are any indication, we shouldn’t expect to see many systems of eight brown dwarf stars either. “Super” planet crash indeed.