First announced 10 years ago, cold fusion has been largely dismissed by the scientific community. But, as David Voss discovers, some researchers remain adamant that this supposed new energy source is real, and are pressing ahead with their own experiments.

Most physicists can probably remember where they were when they first heard of Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischmann. On 23 March 1989 the two electrochemists grabbed the world’s attention by announcing at a press conference in Salt Lake City, Utah, that they had observed controlled nuclear fusion in a glass jar. The excess heat measured in the experiment offered the promise of a new power source for the planet, as well as huge financial rewards.

However, it is clear that world energy production has not been affected in any way by cold fusion. No experiment has so far convinced the sceptics that cold fusion is real, and most of the big funding sources, which threw money at quick experiments in the early days of cold fusion, have pulled out. Retired particle physicist Douglas Morrison, one of the more persistent critics of cold fusion, says that after ten years there is “less science, fewer scientists, fewer funds, [although there are] more potential investors”.

But cold fusion is not dead and buried. A dedicated circle of enthusiasts has kept the flame alive to varying degrees, carrying out jury-rigged experiments in garages and basements, and one or two more conventional institutions still have an interest. Although governments such as those of the US and Japan have officially pulled out, the cold-fusion faithful say that several government agencies are still giving money to the field, including the US Department of Defense. And the Italian and French governments are still supporting research in a small number of labs, according to one cold-fusion insider.

Fusion on a lab bench

A couple of palladium electrodes in heavy water and any high-school kid could do it, it was said. Pons, in the chemistry department at the University of Utah, and his mentor Martin Fleischmann, of Southampton University in the UK, claimed at the press conference in 1989 that they had fused deuterium nuclei using routine electrochemical techniques on their lab bench. This was a huge claim to make – nuclear fusion had been thought possible only at temperatures in excess of a million degrees, when nuclei could overcome Coulomb repulsion. The only cold fusion that had been detected until then was the kind mediated by muons, seen in accelerator experiments in the 1950s, and then only at minuscule rates.

Indeed, questions were soon raised about the reliability of Pons and Fleischmann’s nuclear measurements, given their lack of experience in quantitative isotope analysis. Soon after they announced their findings, laboratories around the world tried but failed to replicate their results. In the rush to duplicate the cold-fusion results, chemists began attempting nuclear physics, and physicists tried to be electrochemists. In the months that followed many labs rushed into experiments, and hastily announced confirmation of cold fusion before they had carried out adequate controls. They then had to make equally speedy retractions when the experiments did not succeed.

Eventually, a group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) found serious flaws in the gamma-ray spectra that Pons and Fleischmann offered as proof. This was to be the death knell, and the final nails in the coffin of cold fusion were hammered in by a US Department of Energy panel that concluded in October 1989 that there was nothing to cold fusion. This in turn spawned bitter accusations that hot-fusion physicists and particle physicists were out to get the cold-fusion community.

The University of Utah continued to press forward with a cold-fusion research institute, but that lab was eventually disbanded in 1991 when it failed to replicate the earlier results. Pons and Fleischmann departed in 1992 for the south of France, where the Technova company, a subsidiary of the Toyota car company, funded a new laboratory called IMRA. As time went on, all but the diehards gave up, and the major reputable labs lost interest and dropped out of the experimental game.

Work on cold fusion continued in several countries, notably Japan, and this was often cited by cold-fusion believers as evidence that that US would be left in the dust when the new world energy order finally dawned. But in 1997 Japan’s government finally gave up. And in 1998 IMRA was closed, having spent something like £12m on cold-fusion work. Then in March 1998 something of a milestone may have been reached. The University of Utah finally gave up its struggle to obtain worldwide patents on Pons and Fleischmann’s work, having been legally bound to pursue patents until last year. The rights now revert to Pons and Fleischmann themselves, should they choose to continue the pursuit of patents.

Sporadic reports have continued to trickle in from various small research efforts, but in each case the results have proved erratic or impossible for other groups to replicate. It appeared to be a classic case of what the Nobel chemist Irving Langmuir called “pathological science”, in which the results are always near the limit of detectability and the proponents always have an ad hoc answer as to why. Yet the defenders of cold fusion have soldiered on, a number of them merging with a network of conspiracy theorists, psychic spoon-benders, UFO enthusiasts and believers in other exotic physical phenomena outside the ken of science.

Cold fusion: the culture

Cold fusion may have been written off by the scientific community at large, but it has entered cultural consciousness in interesting ways. Hollywood embraced the subject in 1997 in the action movie The Saint. Just before the female physicist and the leading man fall into bed for the happy ending, a mythical post-Yeltsin Russia is saved from demented Moscow mafia types by limitless energy generated by electrodes in a bottle. Pons and Fleischmann, though only invoked in the early scenes of the film, stand vindicated. Another film called Breaking Symmetry has just been produced by former MIT materials science professor Keith Johnson. Here, the evil hot-fusion scientists, attempting to protect their millions of tokamak research dollars, engage in various dirty tricks to squelch the discovery of real cold fusion at a fictional lab.

Cold fusion has even been turned into a game. Trevor Pinch of the Science and Technology Studies Department at Cornell University created a hypertext game in which you pretend to be an experimenter trying to replicate the Pons and Fleischmann experiment. Depending on what choices you make, you end up either with your reputation intact or a career in tatters. Cold fusion lives on in other ways too: there is a software product called Cold Fusion for hooking databases to Web sites, a rock band with that name in the US, and a sports equipment company that makes snowboards.

Cold fusion ten years on

What has become of the original protagonists? Martin Fleischmann apparently had a nasty falling out with Stanley Pons over the direction of research at IMRA and returned to Southampton in1995, where he is still working on theoretical models of cold fusion. In a recent phone interview, Fleischmann told Physics World that he just got fed up with his ideas being ignored. He is apparently still collaborating with scientists in the UK and working with Italian scientists to set up a cold-fusion programme. Looking back, he insists that he was thoroughly opposed to any public announcement of the cold-fusion results from the very beginning, but that the University of Utah insisted on a press conference.

Less is known about the activities of Stanley Pons. He has reportedly become a French citizen and now lives on a farm somewhere in the south of France. Owing to bitterness at his treatment by the press and the scientific establishment, he will not speak with anyone outside a small circle of friends and sympathetic cold-fusion researchers. But sources close to Pons say that he is attempting to re-establish himself in electrochemistry research by collaborating with scientists in France, although not in cold fusion.

There are, however, people still active in cold-fusion research. A company in Sarasota, Florida, called Clean Energy Technology (CETI) has reported a process that, they say, produces excess heat and converts radioactive isotopes into non-radioactive material, all in an electrochemical cell containing common-or-garden water. Because cold fusion is the phenomenon that dare not speak its name, CETI is careful to distance itself from the original Pons and Fleischmann work. The principals of CETI are James Patterson, a retired chemist, and his grandson James Reding, a former investment banker. In contrast to Pons and Fleischmann, who were not able to gain patents in the US, CETI has been granted a number of patents for its devices.

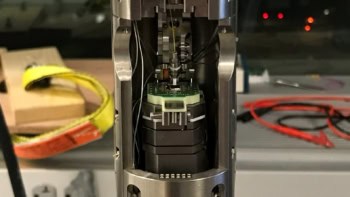

The CETI cell contains palladium-coated plastic beads in a glass flow chamber through which an electric current is passed. Reding says that the company has raised several million dollars to develop the device. On its Web site, CETI says that the US Department of Energy visited them and wrote an encouraging letter, but a spokesman at the DOE says that this was just a standard letter thanking CETI for their invitation to tour the company. One independent researcher who tried to reproduce the work, Barry Merriman of the University of California at San Diego, reports that no excess heat was seen in his experiment. At one time, CETI sold kits to interested researchers, but that has apparently ceased.

One of the early collaborators with CETI, George Miley, a professor of nuclear engineering at the University of Illinois, claims that he has been able to obtain results with the CETI cell in his own laboratory and, moreover, says that he has observed transmutation of elements. Using beads coated with layers of nickel and palladium, Miley says he has observed a range of elements being created electrochemically. Even so, the results have not convinced other researchers, who raise questions about contamination and misinterpretation of the data. For instance, Richard Blue, formerly of Michigan State University, believes the processes going on inside the CETI cell are purely chemical, rather than nuclear. “There are several different elements in the secondary ion mass spectrum, all with the correct natural abundance ratios, ” he says. “The source is an assorted mess of chemical contaminants deposited on the beads through long hours of electrolysis. This is not evidence for any nuclear reaction process.”

Another claim that has attracted attention comes from Les Case, a retired chemical engineer in New Hampshire. Case claims that he has constructed a closed system consisting of palladium-coated carbon pellets and deuterium gas that creates helium-4, one of the possible products of deuterium fusion, when heated. However, Case’s cells were examined at Lockheed Martin Energy Systems, in Oak Ridge, by Lynn Marshall, who says that the amount of helium he measured was the same as background levels. “There was a substantial amount of air in the sample, ” says Marshall, “so there must have been leakage at some point.” Moreover, he explained, the metal bottles that Case sent had fairly low-tech valves that could have easily passed helium either in or out.

The Case cell is now being studied by veteran cold-fusion researcher Michael McKubre at the Stanford Research Institute, using mass spectroscopy to evaluate the helium production. He says that the results are so far inconclusive, but he is planning to discuss his findings at the meeting of the American Physical Society in Atlanta this month. “I’m not going to report anything that I’m not 100% sure of, ” he says. “The field has been embarrassed by premature announcements too many times in the past.”

Overall, the experimental situation remains murky. In spite of the claims by cold-fusion proponents that “hundreds of successful experiments” have provided evidence of tabletop nuclear reactions, the results are not clear cut and are beset by complexity. Hundreds of erratic findings do not necessarily add up to solid proof.

One excuse given for the lack of clear results is low funding. Estimates of cold-fusion funding are difficult at best, but when all the salaries and lab equipment are added up, the cost may total hundreds of millions of dollars – a large number for a phenomenon supposedly achievable on a tabletop. The retort is often given that hot-fusion research has run into the billions, but no one doubts the existence of deuterium-tritium fusion in a hot plasma. No such statement is possible about cold fusion.

Proponents also bemoan lack of access to scientific journals to communicate their work, yet we now have the Internet. Could they not distribute all of the experimental results on-line for critical comment, perhaps on one of the many pre-print servers now available? Part of the problem is that, from the start, many cold-fusion researchers have wanted it both ways – scientific acceptance as well as untold riches via proprietary patent rights. Whatever the next ten years will hold for cold fusion, the field will continue to be a feast for the sociologists of science studying the many ways that research findings become reality, or not.