Physicists Adam Kirrander at the University of Edinburgh and Jon Marangos at Imperial College London are backing a proposal to build the UK’s first X-ray free electron laser, as Hamish Johnston discovers

What is an X-ray free electron laser (XFEL) and what kind of science can be done there?

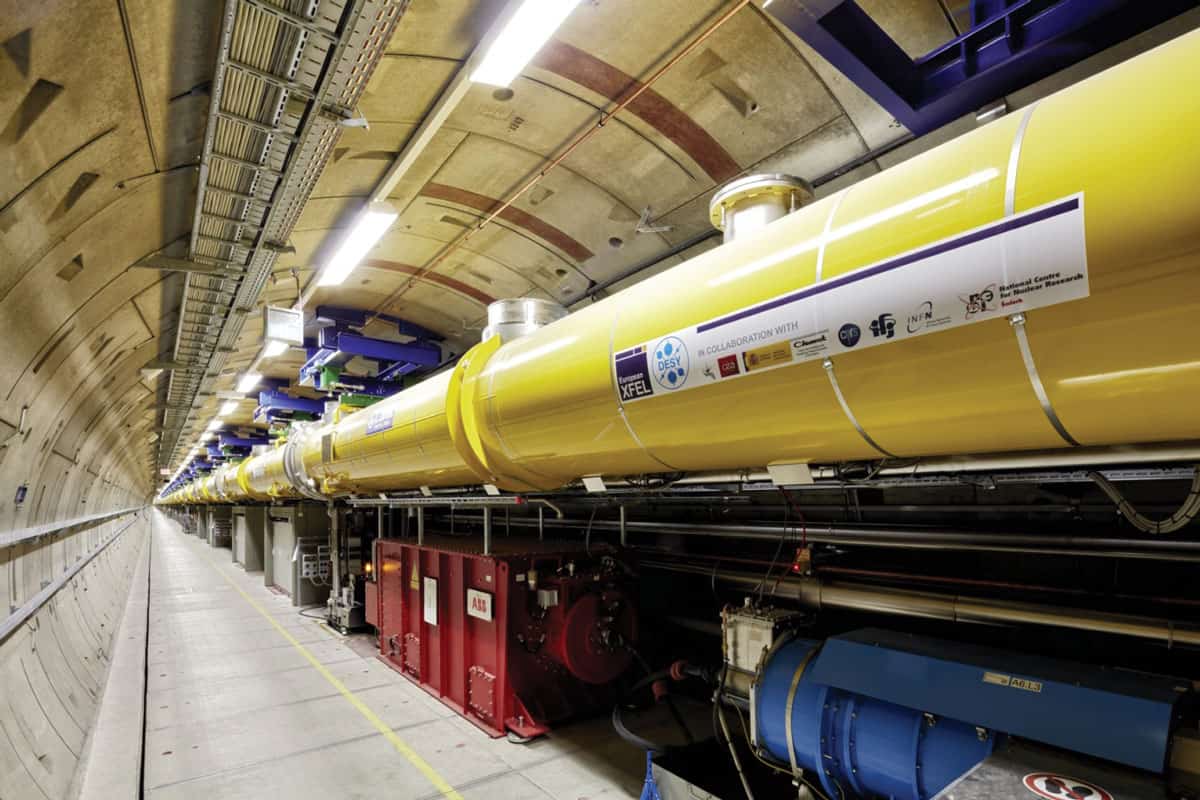

Adam Kirrander: An XFEL is a linear electron accelerator that generates light via a process called self-amplified spontaneous emission or SASE. As a technology it falls somewhere between lasers and synchrotrons and produces light at energies from hundreds of electron volts up to many thousands of electron volts. The light is coherent and emerges in extremely short (sub-femtosecond) pulses. XFELs are also very bright, being many, many orders of magnitude brighter than a synchrotron.

These unique properties open the door for new research across a broad range of physics, chemistry and biology. We can study chemical processes such as catalysis, study quantum materials and determine the structures of biological molecules. Moreover, XFELs can be used to study matter under extreme conditions that normally only exist in the interiors of stars or giant planets – and they can also be used to probe beyond the Standard Model of particle physics.

The UK is a member of the European XFEL in Germany and British scientists can have access to other XFELs worldwide. Why does the UK need its own facility?

Jon Marangos: Existing and future XFELs all have different characteristics, they are not all the same. I use the Linac Coherent Light Source XFEL in California because I need its sub-femtosecond pulses to study really fast electronic dynamics. So today I can’t really use the European XFEL, but that will change in the future.

The number of UK scientists using XFELs has grown rapidly in the past decade from zero to about 500. While many of these scientists use the European XFEL, they move from one international facility to another to get the best possible experimental conditions for their research. If we were to build a next-generation XFEL in the UK, we would expect it to be a fully international facility.

What would the UK-XFEL look like?

AK: The facility’s electron accelerator would be about 1km long and would probably be built in a cut-and-cover tunnel. We want to build a superconducting accelerator with a very high pulse rate. Today’s XFELs run at about 100 Hz but we want to reach the 100 kHz level. The accelerator will drive multiple undulators so we can simultaneously deliver X-rays at different energies to many different experiments in a process called multiplexing.

Our vision is a next-generation facility that does some things that are not currently possible at existing XFELs. One thing we are looking at is the possibility of bringing two X-ray pulses of completely different photon energies together in one experiment or combining electron beams with X-ray photons.

What have you and your colleagues done so far to make the case for UK-XFEL?

AK: This is an ambitious undertaking, and it must be done properly. Over the past 18 months, a large team of scientists has made a very broad assessment of how an XFEL could benefit science and technology in the UK and beyond. This science case has been carefully evaluated by an international panel, which has found it convincing. Now, we need to start thinking about the technical design and eventually there will be a discussion about a location but it is premature to do that now.

JM: At this point in our campaign, we are asking for money to do the conceptual design. We will use this money for technical designs, options analysis and to build our business case carefully. Our proposal would be reviewed by the UK government in about two or three years to decide whether the country will invest in UK-XFEL. The review is conditional on an agreement to fund the next stage of development.

What is next for your campaign?

JM: The next phase will last between two and three years. And it will require some pretty intensive work by some of the UK’s top accelerator scientists and people involved in lasers and photon systems. After that, and if we get the green light, we will go into what’s called a technical design phase where the full details of the facility will be worked out. That will typically take another two years and result in an even heftier volume of material, which would essentially become the blueprint for building the facility. A site can be selected while the technical design is being prepared and construction can start. If everything goes smoothly, we could have first light at UK-XFEL in 10 years, which would be consistent with the timescales of other XFELs

You mentioned choosing a location. Do you see UK-XFEL located at a national lab like Daresbury or Rutherford Appleton, or could the facility be built at a university?

JM: Because of the size of the machine, it’s probably not going to be easy to locate it near the average university. But in principle, yes, it could be built in many locations in the country. It could also be built at one of the existing national research facilities – but it doesn’t have to be. Given the UK government’s current agenda to “level up” deprived parts of the country UK-XFEL could even become part of a new regional science facility – which I think could be a very good thing.