Popularity isn’t everything. But it is something, so for the second year running, we’re finishing our trip around the Sun by looking back at the physics stories that got the most attention over the past 12 months. Here, in ascending order of popularity, are the 10 most-read stories published on the Physics World website in 2025.

10. Quantum on the brain

We’ve had quantum science on our minds all year long, courtesy of 2025 being UNESCO’s International Year of Quantum Science and Technology. But according to theoretical work by Partha Ghose and Dimitris Pinotsis, it’s possible that the internal workings of our brains could also literally be driven by quantum processes.

Though neurons are generally regarded as too big to display quantum effects, Ghose and Pinotsis established that the equations describing the classical physics of brain responses are mathematically equivalent to the equations describing quantum mechanics. They also derived a Schrödinger-like equation specifically for neurons. So if you’re struggling to wrap your head around complex quantum concepts, take heart: it’s possible that your brain is ahead of you.

9. Could an extra time dimension reconcile quantum entanglement with local causality?

Einstein famously disliked the idea of quantum entanglement, dismissing its effects as “spooky action at a distance”. But would he have liked the idea of an extra time dimension any better? We’re not sure he would, but that is the solution proposed by theoretical physicist Marco Pettini, who suggests that wavefunction collapse could propagate through a second time dimension. Pettini got the idea from discussions with the Nobel laureate Roger Penrose and from reading old papers by David Bohm, but not everyone is impressed by these distinguished intellectual antecedents. In this article, Bohm’s former student and frequent collaborator Jeffrey Bub went on the record to say he “wouldn’t put any money on” Pettini’s theory being correct. Ouch.

8. And now for something completely different

Continuing the theme of intriguing, blue-sky theoretical research, the eighth-most-read article of 2025 describes how two theoretical physicists, Kaden Hazzard and Zhiyuan Wang, proposed a new class of quasiparticles called paraparticles. Based on their calculations, these paraparticles exhibit quantum properties that are fundamentally different from those of bosons and fermions. Notably, paraparticles strikes a balance between the exclusivity of fermions and the clustering tendency of bosons, with up to two paraparticles allowed to occupy the same quantum state (rather than zero for fermions or infinitely many for bosons). But do they really exist? No-one knows yet, but Hazzard and Wang say that experimental studies of ultracold atoms could hold the answer.

7. Shining a light on obscure Nobel prizes

The list of early Nobel laureates in physics is full of famous names – Roentgen, Curie, Becquerel, Rayleigh and so on. But if you go down the list a little further, you’ll find that the 1908 prize went to a now mostly forgotten physicist by the name of Gabriel Lippmann, for a version of colour photography that almost nobody uses (though it’s rather beautiful, as the photo shows). This article tells the story of how and why this happened. A companion piece on the similarly obscure 1912 laureate, Gustaf Dalén, fell just outside this year’s top 10; if you’re a member of the Institute of Physics, you can read both of them together in the November issue of Physics World.

6. How to teach quantum physics to everyone

Why should physicists have all the fun of learning about the quantum world? This episode of the Physics World Weekly podcast focuses on the outreach work of Aleks Kissinger and Bob Coecke, who developed a picture-driven way of teaching quantum physics to a group of 15-17-year-old students. One of the students in the original pilot programme, Arjan Dhawan, is now studying mathematics at the University of Durham, and he joined his former mentors on the podcast to answer the crucial question: did it work?

5. A great physicist’s Nobel-prize-winning mistake

Niels Bohr had many good ideas in his long and distinguished career. But he also had a few that didn’t turn out so well, and this article by science writer Phil Ball focuses on one of them. Known as the Bohr-Kramers-Slater (BKS) theory, it was developed in 1923 with help from two of the assistants/students/acolytes who flocked to Bohr’s institute in Copenhagen. Several notable physicists hated it because it violated both causality and the conservation of energy, and within two years, experiments by Walther Boethe and Hans Geiger proved them right. The twist, though, is that Boethe went on to win a share of the 1954 Nobel Prize for Physics for this work – making Bohr surely one of the only scientists who won himself a Nobel Prize for his good ideas, and someone else a Nobel Prize for a bad one.

4. Reconciling the ideas of Einstein and Newton

Black holes are fascinating objects in their own right. Who doesn’t love the idea of matter-swallowing cosmic maws floating through the universe? For some theoretical physicists, though, they’re also a way of exploring – and even extending – Einstein’s general theory of relativity. This article describes how thinking about black hole collisions inspired Jiaxi Wu, Siddharth Boyeneni and Elias Most to develop a new formulation of general relativity that mirrors the equations that describe electromagnetic interactions. According to this formulation, general relativity behaves the same way as the gravitational described by Isaac Newton more than 300 years ago, with the “gravito-electric” field fading with the inverse square of distance.

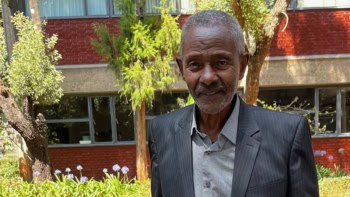

3. A list of the century’s best Nobel Prizes for Physics – so far

“Best of” lists are a real win-win. If you agree with the author’s selections, you go away feeling confirmed in your mutual wisdom. If you disagree, you get to have a good old moan about how foolish the author was for forgetting your favourites or including something you deem unworthy. Either way, it’s a success – as this very popular list of the top 5 Nobel Prizes for Physics awarded since the year 2000 (as chosen by Physics World editor-in-chief Matin Durrani) demonstrates.

2. Building bridges between gravity and quantum information theory

We’re back to black holes again for the year’s second-most-read story, which focuses on a possible link between gravity and quantum information theory via the concept of entropy. Such a link could help explain the so-called black hole information paradox – the still-unresolved question of whether information that falls into a black hole is retained in some form or lost as the black hole evaporates via Hawking radiation. Fleshing out this connection could also shed light on quantum information theory itself, and the theorist who’s proposing it, Ginestra Bianconi, says that experimental measurements of the cosmological constant could one day verify or disprove it.

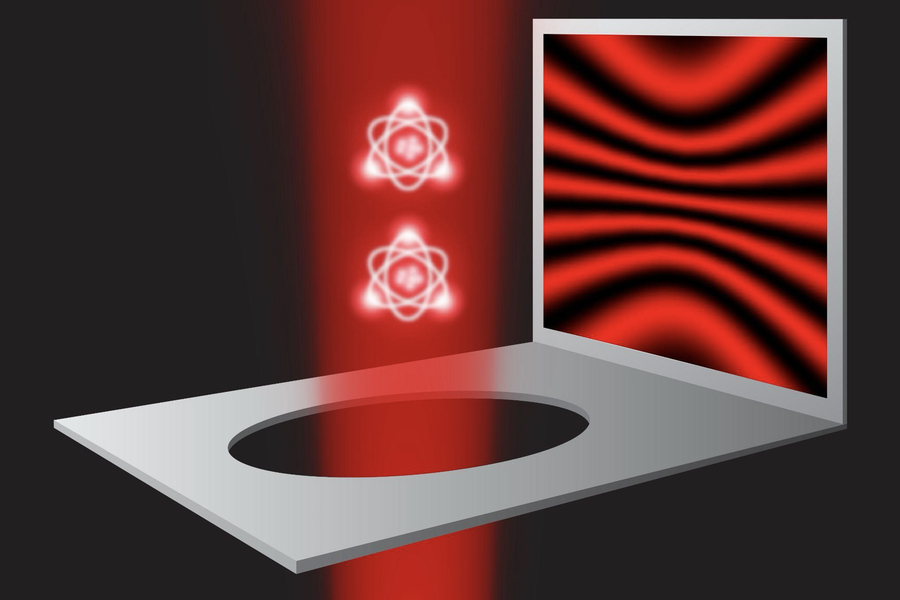

1. The simplest double-slit experiment

Back in 2002, readers of Physics World voted Thomas Young’s electron double-slit experiment “the most beautiful experiment in physics”. More than 20 years later, it continues to fascinate the physics community, as this, the most widely read article of any that Physics World published in 2025, shows.

Young’s original experiment demonstrated the wave-like nature of electrons by sending them through a pair of slits and showing that they create an interference pattern on a screen even when they pass through the slits one-by-one. In this modern update, physicists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), US, stripped this back to the barest possible bones.

Using two single atoms as the slits, they inferred the path of photons by measuring subtle changes in the atoms’ properties after photon scattering. Their results matched the predictions of quantum theory: interference fringes when they didn’t observe the photons’ path, and two bright spots when they did.

Exploring this year’s best physics research in our Top 10 Breakthroughs of 2025

It’s an elegant result, and the fact that the MIT team performed the experiment specifically to celebrate the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology 2025 makes its popularity with Physics World readers especially gratifying.

So here’s to another year full of elegant experiments and the theories that inspire them. Long may they both continue, and thank you, as always, for taking the time to read about them.