- This story is part of Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 250 news outlets to strengthen coverage of the climate story.

Each professor at the University of Montreal in Canada travels on average more than 33,000 km a year, according to a recent study. That makes their carbon footprint nearly double that of most Canadians.

The travel – 90% by plane – is equivalent to three trans-Atlantic trips from Montreal to Paris and back per person each year. The amount of travel varies greatly between professors, however, with some scarcely leaving the university walls while others clock up some 175,000 km, the study found.

“Flying around the world comes at a high environmental price,” says Julien Arsenault of the University of Montreal. “It is very easy to be hyper-mobile, but we should really think hard about how much of this travelling is actually necessary or even beneficial to science.”

Together with co-authors at the University of Montreal and McGill University, both in Canada, Arsenault decided to assess the travel habits of his colleagues as he was involved in a cross-institutional project to reduce the environmental footprint of universities. Although the University of Montreal could supply him and his co-authors with figures for its own environmental footprint – drawn, for example, from its energy usage and food sold – there was no information available on long-distance academic travel.

Reducing air travel does not impact academic productivity, claims study

To generate this information themselves, Arsenault and his co-authors sent a survey to faculty members, research staff and graduate students. The survey set out to establish not just the carbon footprint of academics and students, but also their nitrogen footprint – a metric, gaining in usage, that reflects how much nitrogen a person is responsible for releasing into the environment from crop fertilization, fossil-fuel combustion and other processes. Nitrogen has a range of harmful effects on the environment, including smog, river pollution, and the creation of nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas that is some 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Professors leave nearly 11 tonnes of carbon dioxide and 2 kg of nitrogen in annual per-person footprints, the researchers found, while international students leave nearly 4 tonnes of carbon dioxide and 0.5 kg of nitrogen. “We were surprised by those numbers,” says Arsenault.

A 2015 study by a team at the Lanzhou Library of the Chinese Academy of Sciences found that in 2007 the average Canadian emitted about 13 tonnes of carbon dioxide from their household a year. Assuming academics generate similar household emissions, says Arsenault, their professional travel nearly doubles their overall carbon footprint, from 13 to 24 tonnes.

Arsenault expects the academic footprint to be lower in Europe, where academic institutions are grouped closer together, and larger in Australia, where students and professors seeking to network and attend conferences must travel farther. He also believes the footprint is likely to be much lower in developing countries, where there is less funding available for travel.

“We believe travelling is necessary in many cases: for field research, for young researchers who need to secure employment through networking, or for researchers from developing countries who may benefit from presenting their work in international conferences,” Arsenault explains. “However, established academics from developed countries have, in our opinion, a responsibility to reduce their travel or to minimize its environmental impact.”

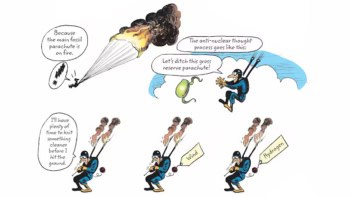

Earlier this year, researchers at the University of British Columbia found no link between air travel emissions and academic productivity, although they did find a link to salary.

Arsenault recommends that the “internationalization” of someone’s research activities should not be rated so highly when recruiting new staff. He also suggests that universities could require their researchers to buy carbon offsets for air travel, and for shorter distances only provide expenses for travel by rail or bus. But, he adds, “the decision to travel is also an individual one. Researchers need to rethink their travel habits.”