To successfully diagnose diseases and disorders, doctors need the best possible tools to see inside the human body. Imaging the body’s tightest spaces without causing damage, however, can be tricky and necessitates camera-like devices that are smaller than was previously possible to engineer. An international team of researchers has now overcome these technical challenges to produce a camera that is small enough to see inside even the narrowest blood vessels.

The team, led by researchers from the University of Adelaide and the University of Stuttgart, has manufactured the smallest 3D imaging probe ever reported. They used 3D micro-printing to put a miniature lens onto the end of an optical fibre that is the same thickness as a human hair. Together with a sheath to protect the surrounding tissue and a special coil to help it rotate and create 3D images, the entire probe is less than half a millimetre across – the same thickness as a few sheets of paper.

Heart disease plaques come into focus

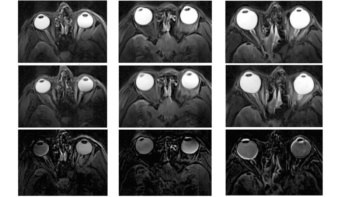

Such a small device can reach into miniscule spaces deep inside the body. The team even managed to see inside the tiny blood vessels of a diseased mouse and a severely narrowed human artery. The ability to look inside these blood vessels gives the researchers hope that their probe could improve the way we understand and treat heart disease.

“A major factor in heart disease is the plaques, made up of fats, cholesterol and other substances that build up in the vessel walls,” explains Jiawen Li, a co-author of the study, published in Light: Science and Applications. “Miniaturized endoscopes, which act like tiny cameras, allow doctors to see how these plaques form and explore new ways to treat them,” she says.

3D micro-printing opens new doors

The new device is not just the smallest, though. It also overcomes many issues that caused other small imaging devices to produce poor-quality images. Previously, the smallest lenses that could be made were simple and often spherical in shape. This led to unwanted effects such as spherical aberration and astigmatism, which prevent the image from being properly focussed and render it blurry. The small designs also struggled to find a good balance between high resolution and good depth-of-field, a measure of how much of the image is in focus.

The new technique of 3D printing more complex micro-optics straight onto a fibre overcomes these issues. Simon Thiele from the University of Stuttgart was responsible for producing these tiny lenses. “Until now, we couldn’t make high-quality endoscopes this small,” he says. “Using 3D micro-printing, we are able to print complicated lenses that are too small to see with the naked eye.”

Given that heart disease kills one person every 19 minutes in Australia, Li predicts that these new devices could be set to make a big impact. “It’s exciting to work on a project where we take these innovations and build them into something so useful,” she explains. “It’s amazing what we can do when we put engineers and medical clinicians together. This project not only brought disciplines together, but researchers from institutions around the world.”