The Trouble with Physics: The Rise of String Theory, the Fall of a Science, and What Comes Next

Lee Smolin

2006 Houghton Mifflin 416pp £25.00/$26.00 hb

“Hypotheses non fingo,” wrote Isaac Newton 300 years ago in the second edition of his Principia Mathematica. It has been variously translated as “I do not make hypotheses” or “I do not feign hypotheses”. Instead, Newton established laws of nature such as his theory of universal gravitation – simple, economical equations of broad explanatory power able to account for diverse phenomena both known and yet to be observed. His natural philosophy became the dominant paradigm of the mechanical world-view and, more generally, what we call the scientific method.

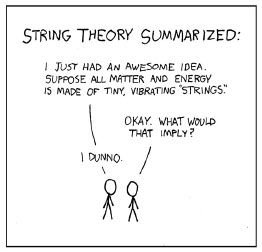

In the last few decades, however, physical theory has drifted away from the professional norms advocated by Newton and other enlightenment philosophers. A vast outpouring of hypotheses has occurred under the umbrella of what is widely called string theory. But string theory is not really a “theory” at all – at least not in the strict sense that scientists generally use the term. It is instead a dense, weedy thicket of hypotheses and conjectures badly in need of pruning.

That pruning, however, can come only from observation and experiment, to which string theory (a phrase I will grudgingly continue using) is largely inaccessible. String theory was invented in the 1970s in the wake of the Standard Model of particle physics. Encouraged by the success of gauge theories of the strong, weak and electromagnetic forces, theorists tried to extend similar ideas to energy and distance scales that are orders of magnitude beyond what can be readily observed or measured. The normal, healthy intercourse between theory and experiment – which had led to the Standard Model – has broken down, and fundamental physics now finds itself in a state of crisis.

Lee Smolin, a theorist at the Perimeter Institute, Waterloo, Canada, has written a thoughtful, provocative book that squarely addresses these problems and advocates a solution in bold new approaches to physics. A principal aim of The Trouble with Physics is to re-engage theory with what actually occurs, or may occur, in the realm of observable phenomena. The book also addresses such core questions as: Why do quarks, leptons and gauge bosons have the diverse masses they possess? What are dark matter and dark energy? How can quantum mechanics and general relativity be combined into a single theory?

String theory originally shared most of these goals, but it got caught up in its own mathematical beauty. Like Narcissus, it increasingly began to contemplate its own reflection, to the exclusion of observable phenomena. To evade comparisons with dross reality, for instance, string theorists have invoked an unseen “metaverse” of parallel universes corresponding to the “landscape” of 10500 possible solutions that might exist. The fact that our universe has spawned galaxies, stars, planets and intelligent life is explained away by the anthropic principle. Of late, a few leading theorists have even begun to suggest a radical new philosophy of science, rejecting Newton, in which hypotheses no longer require observable evidence in order to be accepted as valid theories. To a hardened experimenter like me, this is blasphemy.

So it is refreshing to hear from a theorist – one who was deeply involved with string theory and championed it in his previous book, Three Roads to Quantum Gravity – that all is not well in this closeted realm. Smolin argues from the outset that viable hypotheses must lead to observable consequences by which they can be tested and judged. That is, they have to be falsifiable. Newton’s theory of gravitation, for example, could later account for the orbit of Halley’s Comet – not just those of the Moon and planets for which it was originally formulated. But string theory by its very nature does not allow for such probing, according to Smolin, and therefore it must be considered as an unprovable conjecture.

A worrisome problem is that the general public that follows modern physics does not understand these distinctions and regards string theory as valid science – especially because it gets such broad play in the major media. Recently the US science television programme Nova featured a three-part series on string theory, The Elegant Universe, based on the best-selling book by Brian Greene. Three hours of prime-time television on what is only a hypothesis! And in response to criticism from Smolin and others, Greene recently defended string theory in a prominent essay in the opinion pages of the New York Times.

If we accept string theory as valid while it evades observational tests, how can we legitimately rebut arguments about the “intelligent design” of the universe? The honest answer is that we cannot. For these arguments, too, are not falsifiable; they do not allow testing by measurements. To me, string theory and intelligent design belong in the same speculative, unproveable category, and Smolin apparently agrees. “The scenario of many unobserved universes plays the same logical role as the scenario of an intelligent designer,” he argues. “Each provides an untestable hypothesis that, if true, makes something improbable seem quite probable.”

Towards the end of his book, Smolin suggests other directions fundamental physics can take, particularly in the realm of quantum gravity, to resolve its crisis and reconnect with the observable world. From my perspective, he leans a bit too heavily towards highly speculative ideas such as doubly special relativity, modified Newtonian dynamics and loop quantum gravity. But at least these ideas lead to firm, testable predictions by which they can be judged and – if found lacking – rejected. This is science.

As Smolin recognizes in his concluding chapters, physicists are involved in a struggle for the very definition of what it means to do physics. Is it merely the practice of the men and women who call themselves physicists at any given time? Or are there lasting professional ethics, such as the use of rational argument based on observable evidence accessible to any practitioner? To his credit, Smolin argues forcefully in favour of the latter option. The Trouble with Physics deserves a wide, careful reading by all physicists concerned about the future of our discipline.