Doctor Atomic

John Adams and Peter Sellars

Metropolitan Opera, New York, US

The American composer John Adams uses opera to dramatize controversial current events. His 1987 work Nixon in China was about the landmark meeting in 1972 between US President Richard Nixon and Chairman Mao Zedong of China; The Death of Klinghoffer (1991) was a musical re-enactment of an incident in 1985 when Palestinian terrorists kidnapped and murdered a wheelchair-bound Jewish tourist on a cruise ship. Adams’s latest opera, Doctor Atomic, is also tied to a controversial event: the first atomic-bomb test in Alamogordo, New Mexico, on 16 June 1945. The opera premièred in San Francisco in 2005, had a highly publicized debut at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in 2008, and will have another debut on 25 February — with essentially the same cast — at the English National Opera in London.

Was there ever more operatic material? The Manhattan Project to build the bomb involved several powerful and charismatic individuals who worked amid all-out war to develop a weapon of mass destruction before the German enemy (that also had an excellent scientific-engineering establishment) could do the same. The weapon could potentially kill hundreds of thousands of civilians, but the cost of not developing it seemed greater. The project would have profound social, political and military consequences sure to reshape the world in unforeseen ways. If this is not the stuff of opera, the art form is dead.

Yet historical drama is itself contentious. If the subject is long ago and far away, it does not matter if facts are altered or characterizations changed. While a historian of 16th-century Spain might have trouble with Verdi’s history in Don Carlos, a modern operagoer does not. But when historical drama involves people whose words and deeds continue to affect the present, tampering with elements of history can make the drama collide with our experience of the world and our concerns about historical accuracy. This is what provokes discomfort with works like Oliver Stone’s biopic JFK and Michael Crichton’s novel State of Fear. The former feels like grave robbing, the latter like propaganda.

Doctor Atomic also invites judgement on the issue of historical accuracy, with its libretto announcing that it is “drawn from original sources”. This issue is especially acute for physicists, who may have different reactions to Adams’s opera as artistic expression and as historical depiction.

Musically, Adams’s style is partly minimalist: he relies on repetitive instrumental and rhythmic motifs for the music’s basic framework. At times the choral parts are chant-like and hypnotic. Moments of drama are heightened by changes in instrumentation, density, texture and dynamics. Much of the overall musical effect, in combination with the pageant-like staging, is static rather than forward-moving as in traditional opera. The atmosphere — the growing tension surrounding the imminent testing of the bomb — is highly charged, but everything feels like it is running to stand still.

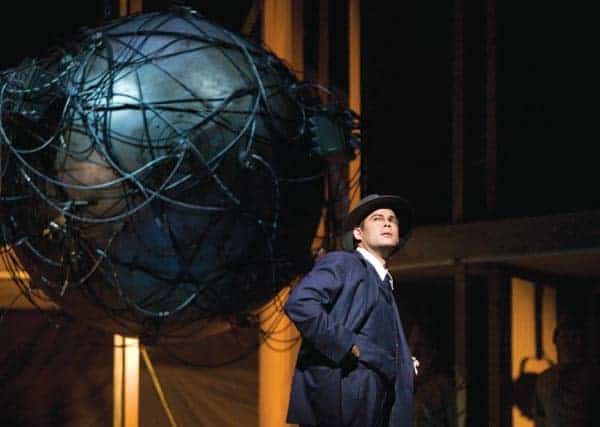

The most notable exception occurs at the end of act 1, when Robert Oppenheimer is alone on stage looking up at the starkly lit, terrifying weapon of mass destruction suspended in mid-air. As he sings “Batter my heart”, a dirge-like aria set to a John Donne poem, a loud, rhythmic interlude suddenly disrupts the aria, rising in intensity and volume, contrasting sharply with its quiet lyricism. This haunting scene is more than a lament: it is Oppenheimer’s soul in turmoil, a turmoil he in fact never articulated. It is a powerful moment, opera at its finest, integrating music, lyrics and staging to disclose more than one could glean from the historical record.

More notable moments include the culmination of the first scene, when the Edward Teller character wonders “Could we have started the atomic age with clean hands?” And at the opera’s climax, the time until detonation arrives asymptotically in a provocative way: we hear the five-minute-warning rocket, seven minutes later the two-minute warning, and the clock continues to tick as time itself seems to run out.

Other arias feel overly long, with a melodic content that is divorced from what is going on orchestrally. Many characters are unevenly realized. When General Leslie Groves, the project’s commanding officer, sings “There is concern our high-strung director might have a breakdown”, this is news to the audience, who have witnessed nothing to make this assertion credible. The aria by Oppenheimer’s maid Pasqualita is overextended, and in combination with the appearance on stage of her costumed kin threatens to portray Native Americans, stereotypically and patronizingly, as innocent, peace-loving children of nature.

Those familiar with the Manhattan Project, the events of which galloped with a terrifying swiftness, may feel impatient with the opera’s slow-moving pace, and legitimately disturbed by the characterizations. When Oppenheimer says that the “nation’s fate should be left in the hands of the best men in Washington”, the words are indeed from an historical document, but an unreliable one — a book by Oppenheimer’s nemesis (and character assassin) Teller.

Teller, in fact, was unsympathetic to physicist Leo Szilard’s petition to withhold use of the bomb. Teller, who died in 2003, had no tolerance for ambiguous aspects of human behaviour, and would denounce as unpatriotic those who were less enthusiastic than he was about the development of nuclear weapons. In later years, he was also often dishonest about his views, particularly with respect to Oppenheimer. It is troubling, if not outrageous, to make Teller one of the principal voices of worry and caution.

Equally problematic is Adams’s portrayal of Oppenheimer’s wife Kitty, the sole female voice among the principal singers, as a tortured earth-goddess who possesses, as Adams put it in one interview, a “cosmic, superhuman awareness of what it all means”. The historical Kitty — a volatile alcoholic, rather than a reflective alcoholic, as she is portrayed here — was not cut out to play this part. Finally, the portrayal of Groves as a stereotypical, buffoon-like military wonk is unjust to the minister’s son who attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, graduated near the top of his class at the West Point military academy, and was a fine engineer and superb administrator.

Deviations from the historical record in an historical drama generally mean that the author is afraid to trust the inherent drama of the actual events. They also tend to reflect the presence of social prejudices and deep-seated cultural myths, which appear — so to speak — to wrest control of the artwork from the artist. Doctor Atomic has passages that are sonorously and visually seductive, and it offers a novel way to portray contemporary events using artistic means. But its historical deviations — which reflect prejudices and myths about Native Americans, patriotism, women and the military mind — are one reason that this ambitious project is not more gripping. The dramatic portrayal of perhaps the single most ethically controversial event of the 20th century should stir up a greater anxiety, and leave us with the feeling that humanity has dirtier hands than we ever imagined.