Titan Unveiled

Ralph Lorenz and Jacqueline Mitton

2008 Princeton University Press

£17.95/$29.95 hb 296pp

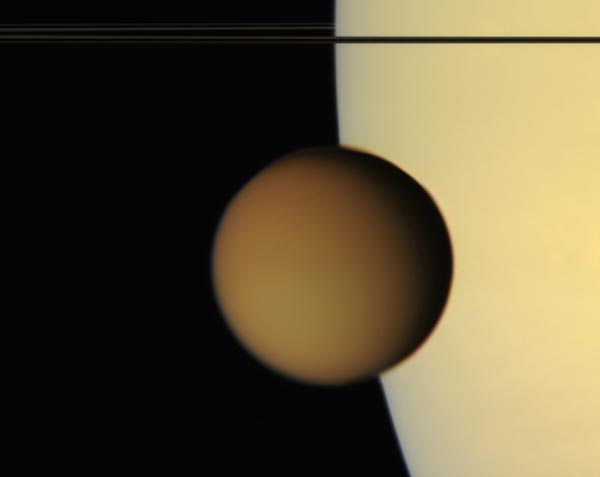

The first planetary satellites (other than our own Moon) were discovered by Galileo Galilei in 1610. These were the four largest moons of Jupiter: Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. Christiaan Huygens followed suit in 1655 by discovering Titan, Saturn’s largest satellite; a few years later, Giovanni Cassini was the first to observe several of Saturn’s smaller moons, as well as the main gap in its rings. It is Titan that stands out, however. Called at first “Luna saturni” and only given its modern name by John Herschel in 1848, Titan is the most massive satellite in the solar system. With a diameter of 5151 km, it dwarfs the other 60-odd moons of Saturn, and is even larger than the planet Mercury.

Modern studies of Titan began in 1944 with Gerard Kuiper’s discovery that it has a nitrogen and methane atmosphere. More recently, NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft flew within a few thousand kilometres of Titan in 1980 on its way out of the solar system. This fantastic journey captured scientists’ imagination and paved the way for the Cassini–Huygens mission. This joint venture between NASA and the European Space Agency was launched in 1997 to study the Saturnian system and Titan in particular. The results of this mission are the main subject of Titan Unveiled, by Ralph Lorenz and Jacqueline Mitton.

The orbiter component of the mission, Cassini, went into orbit around Saturn on 1 July 2004, and is equipped with a radar system capable of penetrating Titan’s thick atmosphere to map its surface in detail. The Huygens landing probe was designed to investigate Titan’s atmosphere during its two-hour descent to the moon’s surface. After landing on 25 December 2004, it analysed Titan’s surface for about two hours before succumbing to the harsh conditions there.

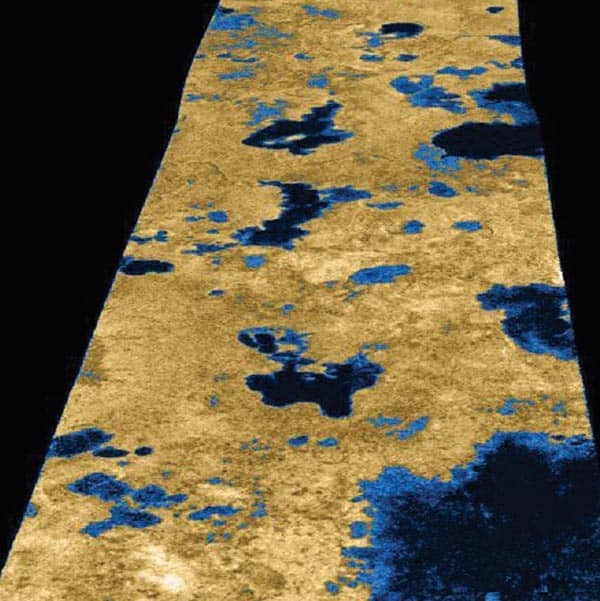

The orbiter mission is still ongoing, keeping hundreds of scientists and engineers from all over the world busy. Breathtaking data have been gathered by both the orbiter and the lander, showing that Titan is an active body with a young surface that mimics an array of terrestrial features. We can observe dunes, rivers and large lakes of liquid methane and ethane from orbit, while images of the landing site show large pebbles made of methane ice. In addition to an overall flat surface, methane clouds have been identified in the southern hemisphere beneath a thick global atmospheric haze. Carl Sagan famously referred to the Earth as a “pale blue dot”; by analogy, we can think of Titan as a “pale orange dot” in space.

Beyond the glamour of exploration, the importance of these scientific results lies in this hydrocarbon world being a laboratory for organic processes, similar to those that are known to have taken place in the early Earth as a prelude to the evolution of life itself. Titan thus opens up a window on our own past.

Titan Unveiled can be seen as a follow-up to another book by the same authors, Lifting Titan’s Veil, which was published in 2002 and focused on the Cassini–Huygens mission before its arrival at Saturn. Lorenz is one of the mission scientists, and his experiences in developing one of the lander experiments, working on both sides of the Atlantic, make him uniquely qualified to take us behind the scenes. Mitton is a full-time writer and media consultant specializing in astronomy.

Titan Unveiled starts with an account of the astronomical discoveries of Titan in the past (particularly in the decade preceding Cassini–Huygens), continues with the development of the mission and closes with a summary of its most relevant results. The mission is described in great detail, including its arrival at the Saturnian system, the descent through Titan’s atmosphere, the probe’s landing and the various orbiter fly-bys.

The atmosphere and surface processes are featured prominently in this exciting account. For example, we learn that Titan’s atmosphere, like that of Venus, contains a “super-rotation” mechanism: the bulk of the atmosphere rotates much faster than the solid moon spins on its axis, with a “quiet” (i.e. slower-rotating) layer about 70 km above the surface. The book also discusses some early theories about Titan that were subsequently proved incorrect, such as the expectation that its atmosphere would contain some noble gases like krypton and xenon, and looks at how we can explore Titan further in the future.

As an active participant in the mission, Lorenz provides an intimate account of this unique adventure. The text combines a lively narrative with a non-technical description of the mission and a summary of the main results, peppered with personal accounts throughout. The drawings and photographs are particularly outstanding.

Titan Unveiled is highly recommended to the intellectually curious general public, as well as to the most seasoned planetary scientists and engineers. In fact, anyone with an interest in science, astronomy, planetary science and exploration, engineering or the evolution of our own planet will find this book captivating and uplifting. Landing on Titan has been one of the greatest adventures of the current decade; in the words of the authors, “planetary exploration gives us a sense of perspective, a notion of who we are, where we came from and what our destiny might be”.

This new field of comparative planetology is at the forefront of human endeavour, and will help us unravel the mysteries of the solar system’s origin and evolution. Thanks to the mission described in this book, Titan can be viewed together with other large, rocky objects in our solar system — the Moon, Mars, Mercury, Venus and of course the Earth — as another completed piece of the planetary puzzle. It has finally revealed its well kept secrets.