So what is the site about?

Hyperphysics is a network of cross-linked articles on topics from acceleration to the Zeeman effect — essentially an online physics encyclopedia. Unlike some sites featured in this column, Hyperphysics is far from new. In fact, by Web standards, it is positively ancient; when it was launched back in 1998 as a “hyperphysics exploration environment”, the search engine Google was still based in a California garage. Today, Google’s algorithms place Hyperphysics entries near the top of results pages for most physics-related search terms — it receives some three million hits per year — and some readers may already have stumbled across the site while searching for physics information on the Internet.

Can you describe a typical entry?

In addition to basic information, diagrams and relevant mathematical expressions, some pages also contain boxes that calculate numerical answers to questions using values typed in by the user. The main page devoted to the Schrödinger equation, for example, begins by explaining how the equation’s potential- and kinetic-energy terms differ from their classical equivalents. Further down the page is a section describing how to calculate the energy of the nth quantum state for a particle in a box — a standard “first problem” in many undergraduate quantum-mechanics courses. A link to “applications of the Schrödinger equation” brings up a map of interrelated subjects such as quantum tunnelling and the hydrogen atom. Such maps appear frequently on the site to illustrate how various subtopics can be traced back to common principles.

Who is it aimed at?

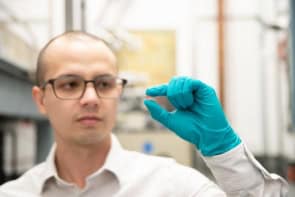

According to its creator Rod Nave, a physicist at Georgia State University in the US, Hyperphysics grew out of a summer course in “conceptual physics” for prospective science teachers. The course was originally meant to give biology and chemistry specialists a basic exposure to physics, but when Nave realized that many of them would actually be teaching physics (due to a severe shortage of physicists), he decided to build something to support them after the course was over. Now, most e-mails he gets about the site come from physics students, who use it to supplement their main course materials, or engineers, who rely on it for general background information.

How often is the site updated?

“Hyperphysics is always considered to be a work in progress,” Nave tells Physics World, and it is updated “almost continuously”. One of the site’s current goals is to incorporate more topics from disciplines like chemistry and biology, so that users can explore the physical principles that underlie them. In addition to this formal programme of updates, Nave says he receives hundreds of e-mails a year containing corrections, suggestions for new topics, and queries about his approach. “The helpfulness of users has been one of the really inspiring things about the project,” he says.

Why should I visit?

Despite its unflashy graphics, Hyperphysics remains one of the Web’s finest and easiest-to-use physics resources. The main topics are listed in an index, and a dense web of links between them allows users to explore a subject in as much or as little depth as they choose. It is not difficult to start off looking for a specific piece of information — the Boltzmann constant, say — and emerge an hour later, newly knowledgeable about both the original question and about apparently distant topics like ionic bonding and the electron affinity of chlorine.