Daniel Whiteson describes how his attempts to explain the Higgs boson to a wider audience led to a collaboration with the artistic brains behind PHD Comics

Sometimes your best ideas come when you are goofing off.

It was just this kind of procrastination that led to my collaboration with cartoonist Jorge Cham and culminated recently in the publication of our new popular-science book, We Have No Idea: a Guide to the Unknown Universe, which uses humour and cartoons to describe some of the deepest unknown questions of physics.

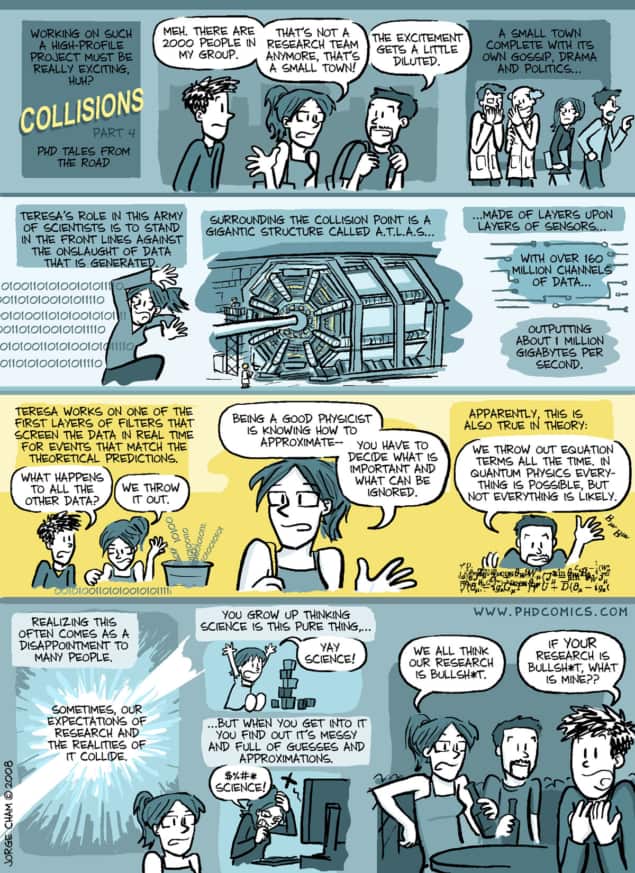

Jorge is the artist behind the popular webcomic PHD Comics, which captures the struggle of life in academia and the frustrating experience of research. But Jorge didn’t start his life planning to be a cartoonist. He first went to graduate school in mechanical engineering at Stanford University in the late 1990s designing robots that could walk in a way that mimics the locomotion of cockroaches, and his original intention was to follow an academic path. But when Jorge needed a mental break from the daily struggles of getting his robot critters to perform, he picked up his pen and starting doodling.

Just a few weeks after starting his graduate studies, he was crafting comic situations that poked fun at the real-life research situations he often found himself in. One was the Professor Negation Zone: a hypothetical region that surrounded his PhD adviser and ensured that any functioning robot would suddenly and inexplicably cease to work when it was time to demonstrate it to his boss. Jorge published these comics three times a week in the campus student newspaper, the Stanford Daily, working on it in his free time and treating it as a fun goof-off rather than the foundations of a future career.

But his comics were wildly popular with the Stanford student population, and soon Jorge took his procrastination to the next level, putting the comics online. They spread around the world, revealing that Jorge had discovered a vein of academic frustration that spanned the globe. He finished his degree in robotics, and took up a teaching position at the California Institute of Technology, but found that academia’s appetite for his comics had outstripped its interest in his robotics research. So in the mid-2000s, he left academia and became a full-time cartoonist. Now, Jorge’s goofing off was his new job.

Freed from the confines of the research lab, Jorge went on the road, visiting universities and research labs around the US, Europe and even Australia. He talked to his hosts about their research, learning about the mysteries they were trying to unravel and hearing about their personal stories. He wrote comics about these experiences, showing the personal side of the scientists and explaining their research in a clever and compelling visual style. This science-communication project expanded the portfolio of PHD Comics from making fun of academic life to explaining its significance.

Goofing off at CERN

Meanwhile, in a research lab across the world, I was doing my own goofing off. I’m a particle physicist by training, trying to understand the fundamental nature of matter by smashing particles together to reveal the universe’s smallest building blocks or to create new, exotic forms of matter. I did my PhD at the University of California, Berkeley, but spent most of my time at the Tevatron particle accelerator at Fermilab, just outside Chicago. Later, I joined the ATLAS experiment at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, which was then searching for the Higgs boson and other new hypothetical particles.

It was 2009 and while my job was often exciting and fun, it could also be frustrating. On a good day, I was writing programs to sift through the vast number of collisions to hunt for the few that might reveal evidence of a new particle, or brainstorming with my students how to design a new particle-physics experiment to hunt for dark matter. But for a practising particle physicist, the days of dramatic discovery are rare; more common are early-morning meetings, avalanches of e-mails about trivial or bureaucratic issues, and a long parade of null results.

So I too felt a desire to branch out from the traditional activities of a particle physicist and develop a side project that tapped into a different kind of creativity. The search for the Higgs boson was heating up and receiving a lot of public attention in the popular press. Some of this was high-quality science communication, but I felt that most of it lacked something that captured the essential ideas and the experience of searching for this elusive particle.

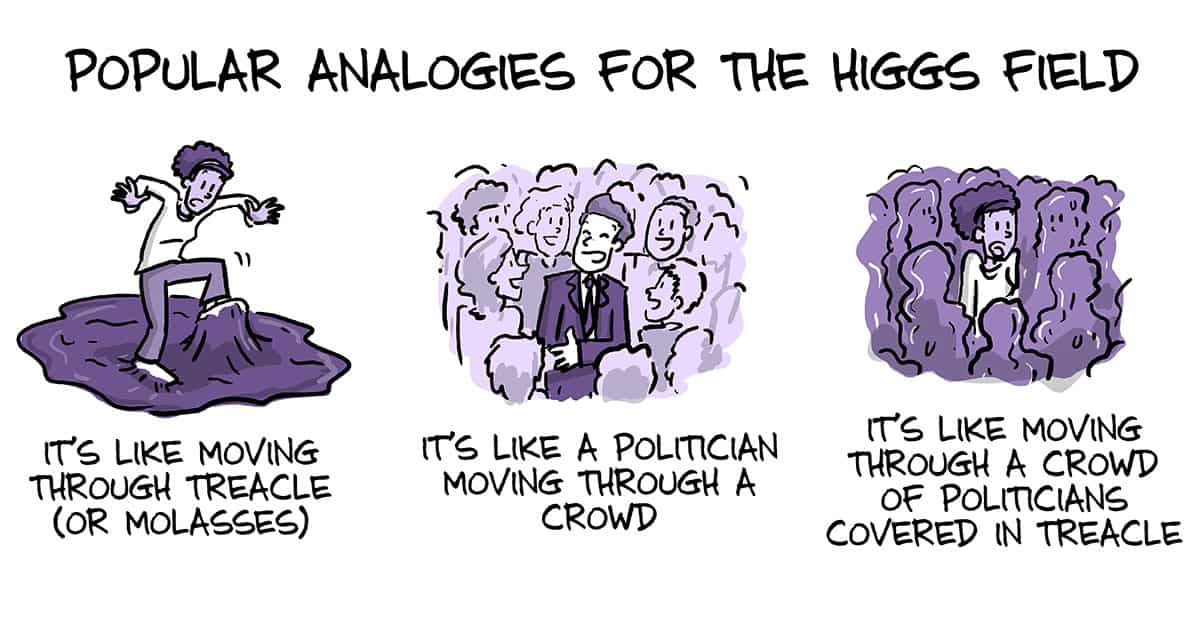

For example, while the discovery of the Higgs boson was a validation of a decades-old theoretical prediction and the last missing piece of the Standard Model of particle physics, it did not put to rest all of our simple but deep questions about the nature of particle mass. The Higgs boson and its associated field are the mechanism that allows the matter particles to have mass, but provides no explanation for the puzzling mystery of their peculiar range of masses. The top quark is extraordinarily massive, while its close cousin the up quark is nearly massless in comparison. Why, then, does the Higgs field give so much mass to one and so little to the other? We have no idea and the Higgs theory provides no answer. Unfortunately, most media coverage about the Higgs boson implied that its discovery would complete the physics effort at the LHC, with all details in place and all questions put to rest.

Like most researchers, I was a long-time fan of Jorge’s comics, and enjoyed his forays into explaining science, ranging from paleontology to neuroscience. Something about his combination of text and informal jaunty visuals brought the ideas through in a way that traditional text-plus-figures had not. I was hoping to work together with Jorge to develop a comic that described our research on the Higgs boson and on the search for dark matter. But partnering with him seemed more like a daydream than a possible reality. After all, Jorge is a celebrity among academics; nearly every research lab I have visited has at least one of his cartoons pasted to the door.

When my wife suggested I e-mail him proposing this collaboration, I scoffed at her naivety. It seemed to me as likely to succeed as e-mailing Brad Pitt and asking him to star in a movie about my life. But e-mails cost nothing, so I fired off a brief message, fully expecting never to hear back.

To my surprise and delight, Jorge responded fairly quickly. Maybe he liked the idea of doing a comic explaining the research at CERN, or perhaps it was that I was offering to pay for his skills. Probably a bit of both. We arranged to meet, and he came down from Pasadena to Irvine and spent a day with me. Particle physics was far out of his realm of expertise, but Jorge has a technical mind and lots of experience asking people questions on a dizzying range of topics. I was impressed with how much of the core concepts he was able to grasp and distil. Our initial plan was to produce a traditional static comic, with diagrams explaining what we were doing at CERN and pointing out why it was interesting and important. Jorge recorded our conversation so he could refer back to it later if he had questions.

But when he sat down to pull the ideas together into a comic, Jorge had a different idea: rather than creating a set of fixed images, he was inspired by a few online science videos to make an animated science cartoon. He edited down his recording of our day-long conversation to a few minutes to make me sound smart and on-point, and added animated drawings to accompany my explanations. When I first saw what he had produced, I was amazed and impressed. It was like a lecturer’s dream. Imagine standing in front of a chalkboard and speaking, while someone with much greater artistic skill draws clever and witty diagrams to illustrate your points.

Our video about the Higgs boson was posted online a few months before its actual discovery was announced in July 2012. At the time, the world’s attention was focused on this mysterious boson – at least for a few days – and many science writers and citizens found our video. It soon went viral, receiving millions of views around the world, and many commented that it was one of the clearest explanations of the Higgs boson they’d come across.

Later, when François Englert and Peter Higgs won the 2013 Nobel Prize for Physics, I was delighted to find that the Nobel Committee for Physics included a link to our video in their list of “further reading”. I suspect it may be the only time my work is mentioned by the Nobel committee, even if it was not the main thrust of my intellectual life, but something I did when goofing off. Jorge and I later collaborated on a video about gravitational waves, which also saw millions of views when the discovery of these subtle ripples in space–time was announced in March 2016.

Unknown unknowns

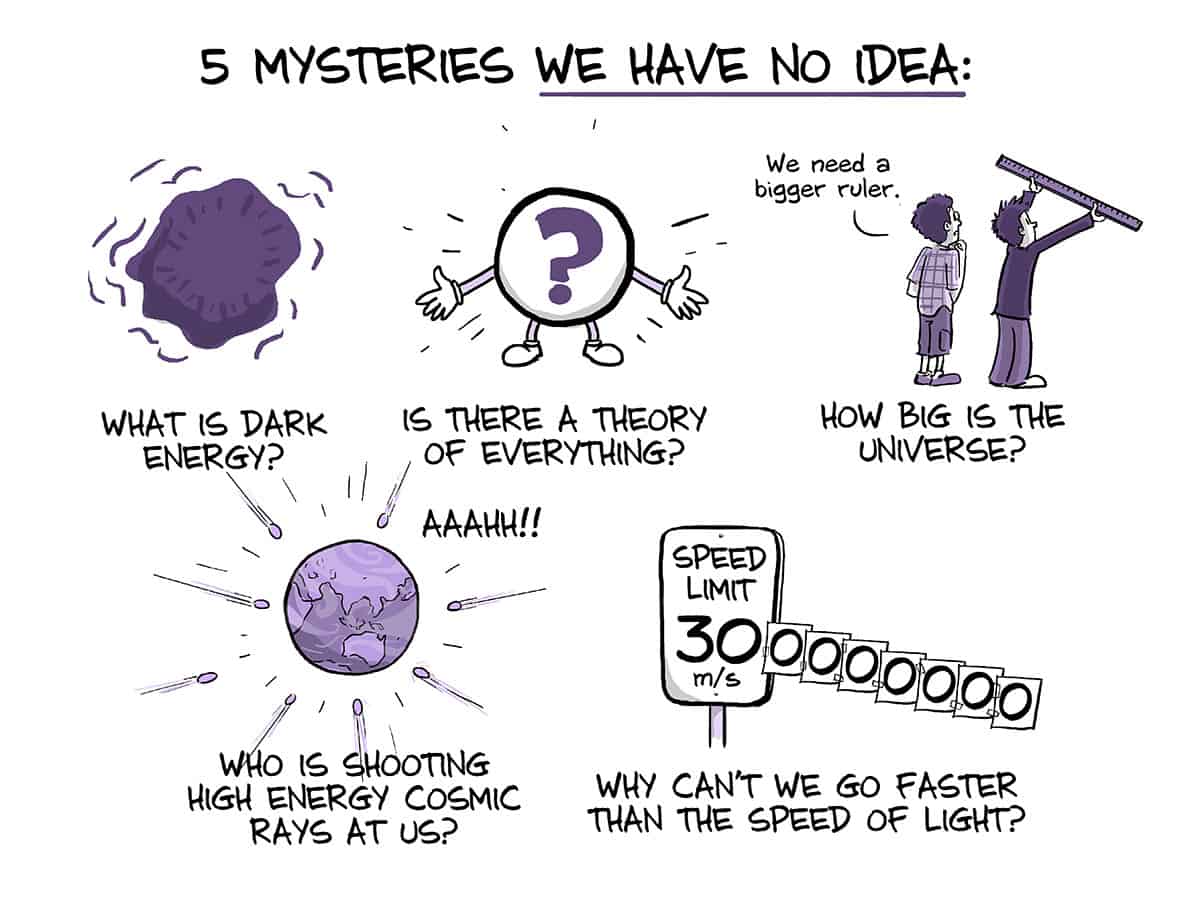

Sometime in 2015 Jorge and I decided to try something different. Most popular-science communication, we realized, focuses on the answers – explaining what we do know. But I felt there’s so much about the world we still don’t know. So rather than developing comics that explain existing scientific discoveries, we thought it would be fun to write a book discussing some of the biggest unsolved questions in the universe. After all, what bigger thrill is there for a scientist than to make a revolutionary discovery that peels back a layer of reality and reveals that the universe is not as we thought it was?

The mystery at the centre of my professional life – “What is the universe made of?” – has seen a lot of progress, as everything around us can be explained in terms of just three basic building blocks: the up quark, the down quark and the electron. Physicists have discovered nine other particles, but why are there 12 in total? Are there more? What explains the strange patterns of their masses and interactions? Are they all built out of one smaller particle?

Even more dramatically, this understanding of matter only applies to 5% of the stuff in the universe. About 27% of the universe is invisible “dark matter” and the other 68% is enigmatic “dark energy”, which is science code for “we haven’t a clue”. And the large questions don’t stop there. The nature of basic elements of our universe, such as space, time and mass continue to elude us. We don’t know either how big the universe is, or if we are alone in it.

Writing the book turned out to be quite different from writing a scientific article. First, Jorge and I discussed which questions to cover, picking those that were interesting at face value and did not need a long explanation or scientific training. That ruled out some fascinating puzzles, such as neutrino oscillation. In some cases, such as dark matter, the material was second nature to me, but in others, such as early-universe cosmology, I talked to colleagues who have deeper expertise and did background research.

For each topic, I wrote a first draft, detailing the importance of the question and then exploring the current ideas. Jorge and I then passed it back and forth until we felt it was as clear as possible – often totally reorganizing the material to reflect his skill in making cutting-edge science accessible. The chapter on gravity, for example, split into two: one on the nature of space itself and a second on the mystery of gravity’s weakness. Once the text was finalized, Jorge would draw cartoons to illustrate the points or make jokes to keep the tone light.

We titled our book We Have No Idea to convey our excitement for the future revelations that physics holds, not to criticize modern physics for failing to unravel them. In speaking to the public about our book, I have been amazed at the passionate curiosity that non-scientists display for these frontier questions, which seem to touch a nerve of human curiosity. Be it string theory, aliens or the early universe, everyone from young children to senior citizens has penetrating questions they want answered.

And though our collaboration grew out of independent efforts at procrastination and distraction, it might just be the best thing we have ever done.