Scientific collaborations often span the globe, but what happens when a potential colleague is someone much closer to home? Benjamin Skuse looks at the lives of researchers where science is a family affair

They may be your childhood co-conspirator or tormentor, your present-day source of pride or envy, but whatever your relationship with your sibling, one thing rarely changes: for better or worse, you are stuck with them for life. By the time they are 11, children who have siblings spend a third of their time – more than with their friends, parents, teachers or on their own – with their brothers or sisters. This intimacy, and the learning and friction that go along with it, means the sibling relationship is one of the most important in moulding an individual’s adult personality. And for those who have caught the physics bug early in life, it can provide the bedrock for staggering success.

From Sophia and Tycho Brahe’s astronomical observations in the 16th century – some of the most accurate to be made without a telescope – to Frank and J Robert Oppenheimer collaborating on the Manhattan Project, examples of successful sibling scientists can be found throughout history. Some, like the Bernoulli clan whose contributions to mathematics and physics stretch over a century, were born into it. Others, like the Wright brothers, drew strength from their mutual love of science to achieve something great. All gained inspiration from their close bond with their sibling.

Brothers in astrophysics

Identical twins Dale and Dan Kocevski are both astrophysicists in the US, at Colby College in Maine and NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama, respectively. Coming from a blue-collar family, and the first in their family to go to college, from an early age the Kocevski twins constantly looked to each other for support in pursuing their nascent scientific interests. “We would take just about anything we could apart to see how it worked and mix random ingredients together from the kitchen in the hope of a chemical reaction,” says Dan. “We often reinforced each other’s preoccupation with science,” agrees Dale. “We attended NASA’s Space Camp in Huntsville, Alabama together and we read a lot and often shared the plots of our respective books, in some sense doubling the number we were reading!” But all this changed at the turn of the century after their bachelor degrees at the University of Michigan.

“We had pretty much spent our entire lives together before going away for grad school,” says Dan. “The loss of the implicit support that comes from having a sibling going through the same challenges was definitely a big deal.” Although they both developed PhD thesis projects related to high-energy astrophysics, their sub-fields – gamma rays for Dan and X-rays for Dale – were worlds apart, meaning the brothers worked on different problems for the first time. “It was a huge change, both academically and personally – it was the first time in our lives that we had lived apart,” says Dale.

Today, while Dale is focused on how galaxies and their supermassive black holes evolve together using observations ranging from X-rays to the infrared, Dan studies the universe through gamma-ray bursts, most recently in relation to searching for the electromagnetic counterpart of the gravitational wave detections made by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory.

This means that despite both working in astrophysics, their professional lives are now largely separate, except for one conference a year that brings them together: the annual American Astronomical Society meeting. “It makes for fun stories when we attend the same conference – I’ve had people tell me how much they liked my talk, only to realize that they were referring to my brother’s talk from earlier in the meeting,” says Dan. “I often wonder how many positions I’ve obtained because people erroneously assumed that I was publishing twice as many papers as I was and on two entirely different fields of astronomy.”

Sharing the same experiences and going through the same changes through childhood, the Kocevski twins are a prime example of how a sibling’s behaviour both influences and is influenced by their brother or sister, in this case in a very positive way.

This contrasts with the commonly held view that rivalry plays a major part in driving siblings to excel in a particular topic. But human development and family expert Kathi Conger from the University of California, Davis, thinks this is a popular misconception. “Negative emotions and feelings are often the focus because that is the stereotype of what people expect about sibling relationships,” she says. While Conger acknowledges there is always the possibility of personality clashes, she says that “the notion of sibling rivalry is overstated in the popular literature”. In fact, a much stronger influence is social learning – the simple act of observation and emulation.

The astronaut and the astrophysicist

For siblings with a large age difference, early-life social learning is more of a one-way affair. Astronomy professor at the University of Kansas and former NASA astronaut Steve Hawley is seven years older than his University of Virginia astrophysicist brother John. “Steve led the way into astronomy for me,” notes John. “I have an early memory of his receiving a telescope as a Christmas present and some number of years later he got a better telescope and gave me the first one as a hand-me-down.”

Despite the age gap, the Hawley brothers’ careers have been strangely intertwined. Prior to his selection by NASA in 1978, Steve conducted seminal work into the nature of peculiar remote elliptical galaxies known as BL Lac objects, which John later followed up by helping to understand the physics underlying them. Then, as a NASA astronaut, Steve serviced the Hubble Space Telescope and the Chandra X-ray Observatory (five trips into space in total), both instruments later providing major discoveries in high-energy astrophysics, which is John’s specialism.

Since then, John has had great success, including sharing the 2013 Shaw Prize in Astronomy with former colleague Steven Balbus for the “discovery and elucidation of the magnetorotational instability”, an important part of the dynamics in accretion discs. “I always remark that the big change was going from people asking me ‘are you related to Steve Hawley?’ to today Steve being asked ‘are you related to John Hawley?’,” jokes John. “Good symmetry there, although his Wikipedia article is much longer than mine.”

Academic heritage

Even if John’s comment is light-hearted, using a brother or sister as a yardstick for your career achievement turns out to be quite common and useful. “Because Rosemary is almost six years older than me, she’s always further along her career path,” explains Louise Dyson, an applied mathematician at the University of Warwick, UK. “I do somewhat measure myself against what she was doing when she was at my stage, and I expect in some ways I always will.”

Louise’s research supports efforts to eradicate neglected tropical diseases. In one ongoing study, she devises models of parasitic worms such as roundworm, which infect the intestine and are transmitted through contaminated soil. Her models focus on the interactions between different parasites when they simultaneously infect a host. Meanwhile, her sister Rosemary is also an applied mathematician but her work at the University of Birmingham aims to understand how plants grow, including modelling the growth of plant roots at a range of scales, as well as the interactions between cells and their extracellular matrix. “I’m also working on an industrial project aiming to produce handheld testing devices that can determine whether there are nasty bugs in your water supply, or blood or urine sample, cheaply, quickly and easily,” she adds.

The Dyson sisters come from an academic family – their mother was a mathematician – so from the outside it was little wonder both sisters followed in their mother’s footsteps. Yet while they were growing up, the very idea of also becoming mathematicians was anathema to them. “It seemed a bit boring if we all ended up doing the same thing,” explains Louise, adding, however, that in the end, maths turned out to be fun after all. Rosemary agrees that they both decided to “do what we were interested in and didn’t let the fact that we wanted to rebel against tradition stop us”.

Family expert Conger says that siblings can be an important source of information, especially if they are working in the same or a related field. They can offer advice and encouragement about the culture of competition and collaboration, share ideas for funding sources, provide feedback on job applications or even help one another in areas outside their immediate expertise. This has been Rosemary’s experience, who has found that her younger sister’s know-how has grown increasingly academically useful in her own work: “She has some really interesting research knowledge and ideas, and I now use her as a resource much more than I used to.”

Family magnetism

But what about siblings who choose wildly different career paths? Does the sibling relationship still confer an advantage in adulthood? All siblings described so far (in this admittedly unscientific sample) seem to share a deep desire to rekindle the closeness of the early-life sibling relationship in later years. However, the gravitational pull is palpable too in siblings who have entirely unrelated expertise, often leading to unusual and impactful results.

The parents of space scientist Sheila, and GP and chief clinical officer Nikki Kanani, surrounded their daughters from a young age with piles of books on human medicine, biology, veterinary science and maps of the universe. Very early on, Sheila decided she wanted to be an astronaut and Nikki a doctor. “We enjoyed the fact that we didn’t have to compete because we were on such different paths,” says Sheila. “We both made our own choices and weren’t compared to each other so we could each flourish as our own person.”

Although they could not support each other academically, Sheila found that having a sister who believed in her “wild” career aspirations gave her the impetus to carry on: “I never felt silly talking to her about what interested me and what I wanted to do ‘when I grow up’,” she says. “Life would be very different without my sister around!”

What is interesting with the Kanani sisters is that despite working in very different areas, they found a topic where they could join forces. “In December 2012 we decided to try and support people from communities that may not be able to access STEMM (science, technology, engineering, maths and medicine) subjects – and STEMMsisters was born,” explains Sheila. STEMMsisters is an online social network that includes mentoring, events and a blog, all of which aim to connect, inspire and empower anyone interested in the STEMM subjects. “We have similar strengths but also both bring different ideas to the table and we bounce off each other very well,” says Sheila. “Working with your sister is super fun: like doing your dream job with your best friend!”

Quantum connection

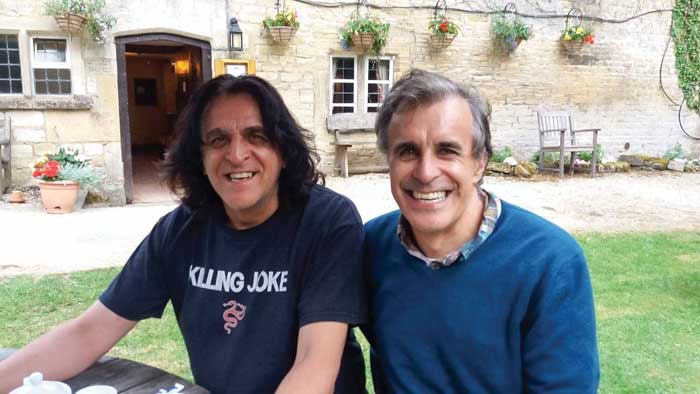

An even more extreme example of sibling collaboration can be seen in Rutgers University condensed-matter physicist Piers and his younger brother Jaz Coleman, who is the co-founder of, and singer in, the hugely successful industrial rock group Killing Joke. With one brother travelling the world as an international rock star and the other studiously advancing the theory of strongly correlated electron systems, the Colemans’ worlds could not be further apart. Yet at the start of the century they found a way to collaborate. Music of the Quantum merged Piers’ knowledge of quantum mechanics with Jaz’s musical skills to create an original musical composition about the quantum world.

“One of the things I told Jaz was that quantum mechanics allowed things to be in two states at once, and that perhaps we could try to capture this in the music,” says Piers. “Jaz had the idea of using a violin and an accordion to capture these two states.” Music of the Quantum was first performed in New York at Columbia University in 2003 and then in 2004 at the Bethlehem Chapel, Prague. “It was immense fun, though a huge undertaking,” says Piers. “We hope to perform Music of the Quantum again live in London. I love the idea that art and science are not so far apart – the idea that they can synergize one another.”

Clearly, siblings can have a big effect on each other’s life course. From the very beginning, the bickering, fighting and arguing that is usually frowned upon or punished by parents can confer an advantage when it comes to problem-solving in adulthood – a key tool for any scientist. “It seems likely that siblings who learn to resolve conflicts are in a better position to state their case clearly, take a stand and stick up for their point of view,” Conger says. “My research found that sibling problem-solving skills contributed to an adolescent’s sense of mastery and control even after taking into account problem-solving with parents.”

By negotiating new roles and responsibilities outside the home, and incorporating new relationships into their lives, at some point, however, family relationships – including those between siblings – start to become less central to everyday life. But once established in their careers and settled in their family lives, that familiar bond often seems to once again tug siblings back together. And with the angst and rivalries in the past, the warmth of the bond restored, and knowledge from a lifetime devoted to their passions at their fingertips, older sibling pairs can become more than the sum of their parts in achieving great things side by side.

Historical sibling scientists

Gifted siblings litter science’s annals with huge achievements. Here is just a small selection of some of the most notable.

Tycho (1546–1601) and Sophia (1559–1643) Brahe

The youngest of 10 children born to Danish high nobility, Sophia Brahe taught herself astronomy, astrology, mathematics, chemistry, medicine, genealogy, botany, literature and German. She assisted elder brother Tycho in his astronomical observations – some of the last to be done with the naked eye – which produced by far the most accurate measurements of the positions of the planets and astronomical objects at that time and led to new understanding of what comets and what we now know as supernovae are.

The Bernoulli mathematicians (1654–1789)

Hailing from Basel, Switzerland, various Bernoullis made a huge impact on mathematics in the 17th and 18th centuries. Brothers Johann and Jacob inspired and competed with one another, leading to progress in infinitesimal calculus, including the development of the calculus of variations. Johann’s sons Nicolaus, Daniel and Johann II, and even his grandchildren also became accomplished mathematicians and teachers. Daniel Bernoulli, in particular, is today known for Bernoulli’s principle on the inverse relationship between the speed and pressure of a fluid or gas.

William (1738–1822) and Caroline (1750–1848) Herschel

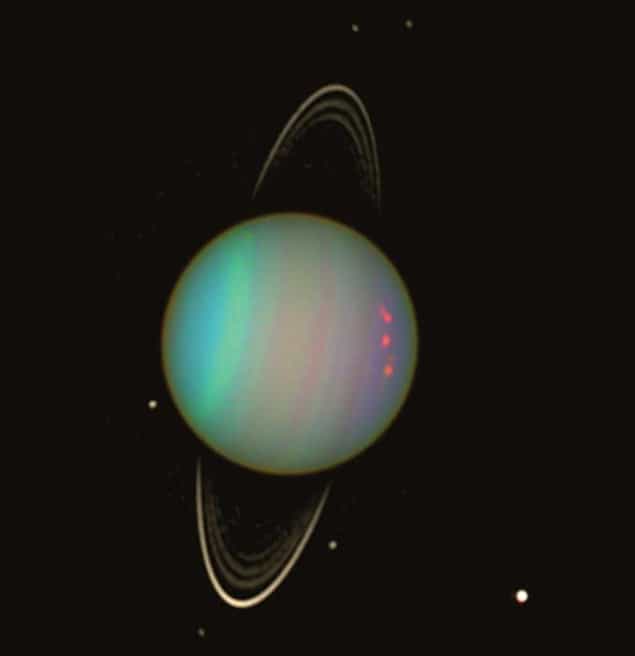

The first professional astronomer, German-born William Herschel is probably best known for discovering Uranus and its moons Titania and Oberon, as well as discovering the Saturnian moons Enceladus and Mimas, and importantly, was the first person to identify infrared radiation. Meanwhile, sister Caroline assisting in the shadow of her esteemed brother was the first woman to discover a comet, to be paid for scientific services and to receive an honorary membership into the Royal Society. Until 1996 she was the only woman to receive the Gold Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society.

J Robert (1904–1967) and Frank (1912–1985) Oppenheimer

J Robert Oppenheimer was an American theoretical physicist, who made important contributions to theoretical astrophysics, nuclear physics, spectroscopy and quantum field theory. Frank was inspired to follow in his older brother’s footsteps, which eventually led to him collaborating with Robert, who was director of the Manhattan Project, on the creation of the atomic bomb. However, Frank’s brief dalliance with the Communist Party in the 1930s put an end to his scientific career after the Second World War and damaged his brother’s. Later, Frank recovered by founding San Francisco’s Exploratorium in 1969, which has inspired science museums worldwide ever since.

- Enjoy the rest of the August 2017 issue of Physics World in our digital magazine or via the Physics World app for any iOS or Android smartphone or tablet. Membership of the Institute of Physics required