Come October, it will be the 10 million kronor question: who’s going to win the 2008 Nobel Prize for Physics?

Of course, every physics buff will have a tip to share. But if a study by researchers in Canada is anything to go by, it is much harder to predict — and perhaps choose — winners today than it was half a century ago.

Yves Gingras and Matthew Wallace at the University of Quebec, Montreal, based the study on citation data of physics and chemistry Nobel laureates from the prize’s inception in 1901, when Wilhelm Röntgen picked up the first physics award for the discovery of X-rays, through to last year, when Albert Fert and Peter Grünberg shared the physics prize for their discovery of giant magnetoresistance.

Using this data, Gingras and Wallace ranked the laureates among their contemporaries in terms of how often their papers are cited by others, and then analyzed how the ranks changed with time. The result was a year-by-year list of the most influential scientists, which the researchers could compare with the awarding of Nobel prizes.

‘More difficult now than ever’

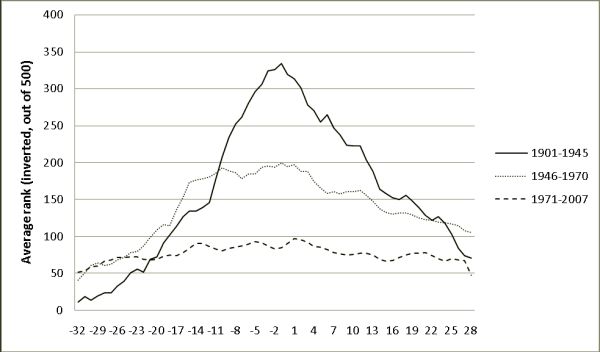

In the run-up to 1945, Gingras and Wallace’s analysis portrays Nobel laureates as leading lights in physics (see graph). The data reveal that, during the course of the scientists’ careers, their citation rankings peaked strongly about a year before their Nobel recognition, implying they were a dead-cert. After they received the prizes, their rankings decreased more slowly — presumably, say Gingras and Wallace, propped up by the kudos or “halo effect” of being a laureate.

After 1945, however, it is a different story. With every year gone by, the ranking of Nobel laureates goes down and down until they are barely distinguishable from other top-level scientists. In fact, in the period from 1971 to 2007 there appears to be no peak in the citation ranking of the prize winners at all (arXiv:0808.2517).

Gingras and Wallace attribute the lack of stand-out laureates to the growing number of sub-disciplines in science: “It is obvious that science has grown exponentially over the 20th century…to such an extent that the fragmentation of science makes it more difficult now than ever to identify an obvious winner for a discipline as a whole.

“Whereas it was still relatively easy around 1910 to know who the most important scientists in a discipline were, such a judgement is much more difficult since at least the 1970s.”

Prediction is ‘almost futile’

The analysis raises the question of whether the Nobel Prize for Physics is as prestigious as it was in the first half of the 20th century. Gingras and Wallace stop short of making this connection, though they do suggest that the Nobel committee has a much harder time picking out the best candidates; this might be borne out in the fact that there have been no unshared awards in the past 15 years. Certainly, they say that “the game of prediction” is “almost futile”.

“It is true that it takes longer for recognition now than, say, in the 1920s and 1930s,” says Lars Brink, a member of the 2008 Nobel Prize for Physics Committee. “This is partly due to the fact that physics is more developed and that it takes a longer time to do experiments and to verify theoretical ideas.”

Brinks adds, however, that he does not think that fact makes it harder for him and his colleagues. “It has always been a difficult and time consuming job,” he says.

The Quebec researchers also avoid the fact that Nobel prizes are, more often than not, awarded on the basis of a single discovery — not on their performance in league tables. As Arne Tiselius, erstwhile head of the Nobel chemistry committee, wrote: “You cannot give a Nobel for what I call ‘good behaviour in science.’”