Scientists were already aware that the huge black hole at the centre of our galaxy does not consume large amounts of matter, but it could be an even pickier eater than previously thought. That is according to new research done in the US that suggests that the black hole – called Sagittarius A* – has a tendency to blow away 99.99% of the matter available for its consumption.

Supermassive black holes are awesome phenomena that are believed to exist at the centre of most, if not all, galaxies. They are hundreds of thousands to billions of solar masses and expand by feeding on dust that is blown off massive young stars just outside the black hole’s event horizon – the zone beyond which not even light can escape.

In the Milky Way, these neighbouring stars are located a relatively large distance away from the black hole mass. For this reason, scientists had calculated that Sagittarius A* should consume only about 1% of the available dust. But now a team of astronomers, including Roman Shcherbakov of Harvard University, claims that it is consuming much less than that.

Gaseous lobes

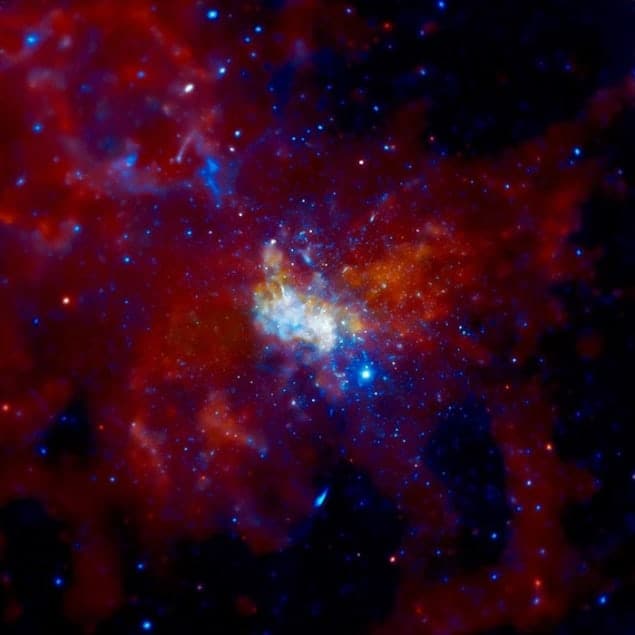

The team studied an image constructed from a series of observations captured by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, over almost two weeks. This long exposure time, enabled the researchers to get a clear view of the gas surrounding the event horizon, which revealed a series of gaseous lobes stretched in various directions.

To explain this observation, Shcherbakov and his colleagues employ a model that considers the flow of energy between two regions around the black hole: an inner region that is close to the event horizon, and an outer region that includes the black hole’s fuel source – the young stars – extending up to a million times farther out than the event horizon. They conclude that collisions between particles in the hot inner region transfer energy to particles in the cooler outer region via conduction, which adds an additional outward pressure so that all but 0.01% of the incoming star dust is blown away.

These findings were presented at the 215th annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS), which is taking place this week in Washington, DC.