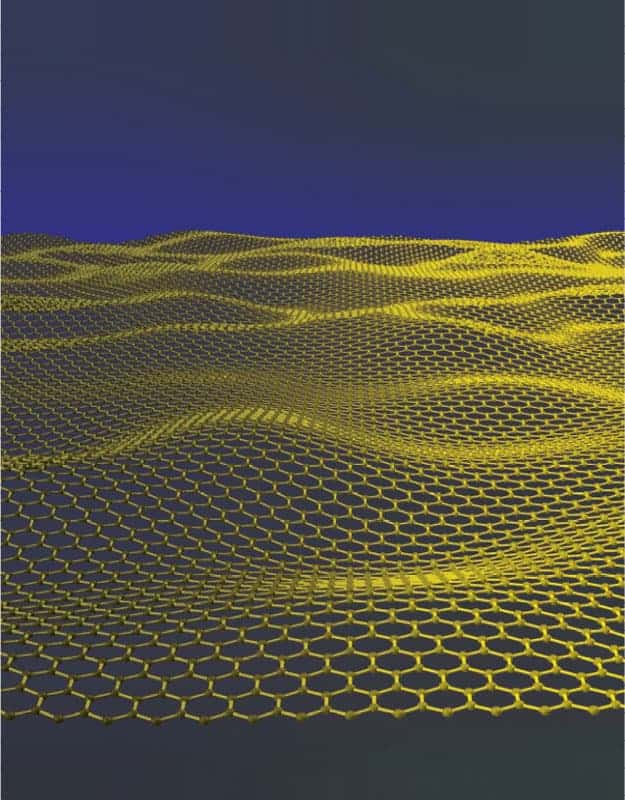

Could insights into the elusive Higgs boson – the particle being eagerly sought at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC) – come from a simple solid material? Yes, according to a trio of physicists in Spain, who argue that vital clues could come from looking at graphene – a sheet of carbon just one atom thick. They argue that ripples in this material arise from a spontaneous symmetry-breaking process similar to that which separated the weak and electromagnetic forces in the early universe.

At the high energies of the early universe, the weak nuclear force and the electromagnetic force are thought to converge into one electroweak force. As the temperature of the universe fell below a certain point, the two forces suddenly became separate. This “electroweak symmetry breaking” can be explained in terms of a field – the Higgs field – shifting from an effectively empty high-energy state to its ground state, filling space with a field that gives some particles their mass.

The yet-to-be-detected Higgs boson is the particle associated with vibrations of this field, and is currently being sought in the LHC. But what exactly drives the Higgs field between the high-energy and ground states? Although the parameters in the Standard Model of particle physics can be adjusted to force the symmetry-breaking, it is possible that the Higgs field may not need any coaxing. Pablo San-Jose and colleagues at Madrid’s Institute for Material Science now argue that studies of the emergence of ripples in graphene could shed some light on the process.

Hats off for the Higgs

Spontaneous symmetry-breaking lies at the heart of the analogy – graphene loses some symmetry in the transition from a flat shape to a rippled one, in the same way as the “activation” of the Higgs field is tied to the breaking of the electroweak symmetry. Compared with grand cosmological scales, sheets of carbon might seem a bit pedestrian, but San-Jose thinks otherwise. “Measuring the rippling of graphene under variable tension could give us information about the details of the intrinsic condensation of the Higgs,” he says.

Working with colleagues Francisco Guinea and Jose Gonzalez, San-Jose claims to have shown that the energy landscape of graphene rippling in 2D and that of the Higgs field in 3D, are described by similar “Mexican hat” potentials. Like a sombrero, the potential energy starts high in the centre but quickly falls away to a minimum in any direction. The negative curvature at the top ensures that symmetry will break spontaneously – any push from the centre sends the system down towards a stable point in the brim, just where the edge of the hat begins to climb again.

In the case of graphene, the negative curvature is a result of how graphene responds to being stretched or compressed. In particle physics, negative curvature is a result of the relationship between the Higgs field and the “bare” mass of the Higgs boson. In order to be unstable, this bare mass must be imaginary – the Higgs boson acquires a real, effective mass when the field reaches its true stable ground state.

According to San-Jose, studying how graphene responds to compression by buckling into ripples could give hints about how the Higgs condenses. Small, spontaneous ripples in the absence of compression, for example, would suggest that the Higgs field may condense without requiring an imaginary bare mass for the Higgs boson. Experiments could also probe the structure of the potential in cases where the ripples are larger, providing information about mathematically difficult details of the Higgs quantum field theory.

Tunable using electrons

Vitor Pereira, a condensed-matter physicist from the National University of Singapore, is interested in the Spanish team’s explanation for how these ripples arise in graphene, which it sees as being via interactions between electrons and deformities in the structure that soften the material. He suggests that graphene’s structure might be tunable through the control of electrons.

Pereira adds that graphene’s properties may mimic other experimentally difficult processes, such as how particle–antiparticle pairs arise in the vacuum. Although some researchers are sceptical about accuracy of such models, he thinks otherwise. “It is quite cool to use graphene, arguably the simplest of the condensed-matter systems, as a testbed for such sophisticated ‘high-energy’ phenomena,” he says.

The work is reported in Phys. Rev. Lett. 106 045502.