Researchers in the US claim to have the most reliable estimates yet of the amount of energy that the Sun provides to Earth – and it is less than previously thought. The findings will give scientists more robust solar data to feed into climate models, though much more work needs to be done to fully understand the relationship between the Sun and the Earth.

Historical and geological records reveal that the Sun has remained relatively stable for the past 250 years, with the total solar irradiance (TSI) fluctuating by less than 1% over the roughly 11-year solar cycle. And since the first space-based radiometers were launched in the late 1970s, scientists have been able to measure this irradiation directly. But to date, these space measurements have remained uncalibrated – researchers had to assume that their instruments function in the same way in space as they do on Earth.

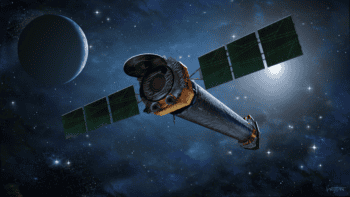

Greg Kopp of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) in Boulder, Colorado, and Judith Lean of the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington DC say they have acquired a more reliable estimate of solar activity. They analysed data collected by NASA’s Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment (SORCE), a satellite launched in 2003 to investigate why solar variability occurs and how it affects Earth’s atmosphere and climate.

Simulating space on Earth

Crucially, Kopp and Lean were able to calibrate data collected by the Total Irradiance Monitor (TIM) instrument aboard this craft at a new calibration centre at LASP. This facility in Boulder enables researchers to verify their findings by recreating the conditions of interplanetary space with vacuum operations and high solar power levels. Kopp and Lean find that the TSI during the last solar minimum in 2008 was 1360.8 ± 0.5 W m–2, which is roughly 5 W m–2 less than the accepted value used in climate models.

“Although it seems small, this level of difference is very large for the instruments acquiring these measurements,” Kopp tells physicsworld.com. He says that while the latest finding is purely an improvement in instrument accuracy, it can help to inform climate studies about the influence of the Sun.

“The major climate models agree that the majority of climate change over the last century is caused by changes in greenhouse gases, while the Sun’s influence is responsible for about 15% of the observed warming over this time,” he says. “Prior to the 1900s, the Sun was responsible for much more of the changes in Earth’s climate.”

Little Ice Age

Indeed, geologists agree that over the course of Earth’s history, variations in the Sun’s energy output are likely to have influenced the climate on Earth. The “Little Ice Age”, for instance, which extended from the 16th to the 19th century, is often linked with a roughly 70-year stretch beginning in 1645 known as the Maunder Minimum when the Sun was particularly weak.

Friedhelm Steinhilber, a geologist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, near Zurich, agrees that Kopp and Lean’s measurements of TSI are the most accurate to date. But he warns that the significance of the lower value is far from fully understood.

“The Sun’s influence on Earth’s climate is not so much the absolute value. It is the relative variation”. Steinhilber believes that the significance of solar fluctuations is only really felt over longer time periods, like that observed during the Maunder Minimum.

These findings are presented in a paper in Geophysical Research Letters.